The Underground Railroad

The Underground Railroad, Barry Jenkins’s adaptation of Colson Whitehead’s Pulitzer-winning 2016 novel, is the best television show of 2021. I know we’re not quite at the halfway point of the year yet, but it’s still true. It is basically impossible that a better series will come along this year. It might even be the best television series of 2022 and 2023. It’s also gotten a little buried—maybe because of the difficult subject matter, maybe because Amazon dumped the whole season at once, and really, I can’t imagine a series less suited to binge-watching, and maybe because audiences are willing to watch a historical drama about slavery, but they don’t quite know what to do with a magical realist story it. The Underground Railroad, in case you haven’t read the book and haven’t heard anything about it, literalizes the historical metaphor by imagining that there is a real railroad beneath America that carries runaway slaves, like the novel’s heroine Cora, away from slavery. But the railroad moves not only through space but through history, delivering Cora and her traveling companions to locations that illustrate the different forms that the oppression of African-Americans has taken throughout America’s existence. Jenkins, the Oscar-winning director of Moonlight, is the perfect match for the material, using his control of color and light to create an America that is half a dream world, and elaborating on the novel’s idea of the railroad by making it a world in its own right.

I have a post on my blog about the show—not a review (though it includes links to several reviews; I’m particularly fond of this one by Angelica Jade Bastién) so much as a series of observations about the way it approaches its subject matter, how Jenkins brings cinematic storytelling methods to TV in a way that I’ve never seen before. and how it expands on the ideas of the original novel—for example, in taking a wider view of the white society around runaway heroine Cora.

This is only one of the ways in which The Underground Railroad diagnoses white American society with spiritual poverty, a sickness rooted in the need to justify slavery and the extermination of Native Americans. Ridgeway, for example, points out that his father’s “great spirit” philosophy is borrowed (and probably heavily bastardized) from Native Americans, a tacit acknowledgment that even this partial, insufficient version of goodness can only come from outside of American whiteness. In North Carolina, Cora is hidden in the attic of the local station master, Martin (Damon Herriman), whose wife Ethel (Lily Rabe) is bigoted and hostile. Ethel is also a devout Christian, and tries to give Cora religious instruction, never perceiving a contradiction between her bigotry and her claim to moral superiority. But though everyone in the episode proclaims their religious belief, it’s made clear that the primary purpose of their version of Christianity is to justify exploitation and genocide. The result is a psychic wound, a creed that offers its adherents neither a reliable guide to living a righteous life, nor a foundation for moral courage. When Martin and Ethel are exposed, they try to cling to their faith, but it proves pathetically insufficient.

Throughout the season, The Underground Railroad keeps returning to the image of white children and youths being taught the precepts of white supremacy and manifest destiny. When Cora first escapes slavery, she kills a boy who tries to recapture her. That murder is repeatedly brought up—mostly by Ridgeway but also by others, including some of the inhabitants of Valentine Farm, who are no less horrified by it than he is—as a reason why Cora is no normal runaway, and why she doesn’t deserve liberty. But the season’s emphasis on the indoctrination of white children suggests another interpretation: that the real culprit in this boy’s death is the society that taught him to look at a woman fleeing enslavement, and put himself on the side of her enslavers. A society that would rather kill its own children—be it a death of the body or of the soul—than give up its addiction to exploitation. It’s a decisive rebuke to the way that so many stories about slavery get bogged down in the question of whether this particular white person is good or bad. The answer, The Underground Railroad finally concludes, is that they’ve all drunk poison, and it’s the system feeding them that poison that is the real villain.

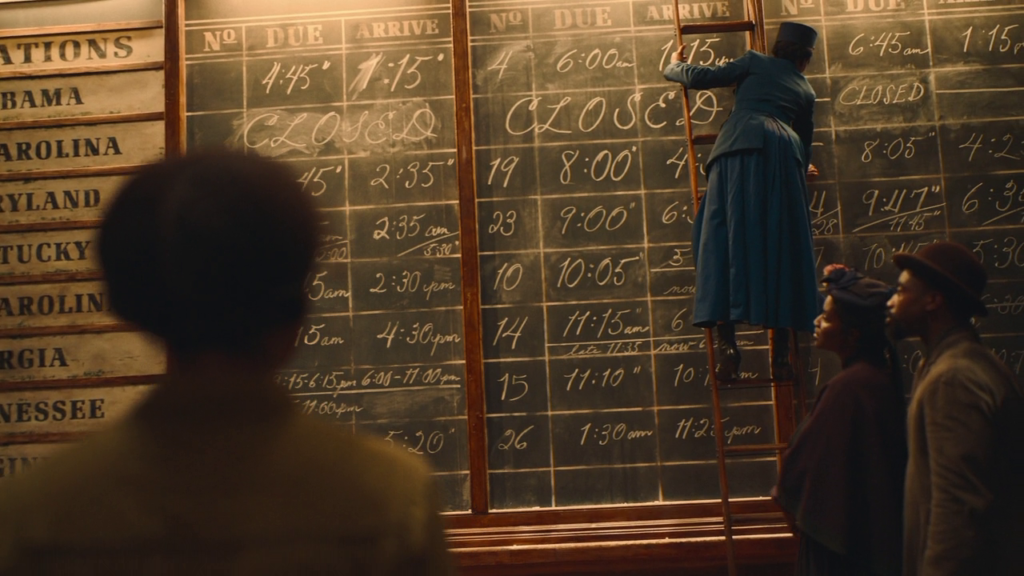

You can read the whole thing over at my blog, but for now, I thought we’d look at some more images from the show. Here is Cora on her first stop on the railroad, in the supposed liberal haven of Griffin, South Carolina, where they take slaves in and educate them, but also have dark designs for their future.

Here are Cora and the slave catcher Ridgeway (Joel Edgerton) trudging through the burned-out Tennessee landscape.

Cora and some friends (including William Jackson Harper’s Royal, a railroad station master) are about to get on the train.

Cora and Royal share a moment.

The hub of the underground railroad, which may be real, and may be a dream, and may be a space between life and death.

Over at Vimeo, Jenkins has published The Gaze, a series of outtakes, or offshoots, or short, wordless films set in the world of the show.

It’s a work unlike any that has been seen on TV, and a masterpiece to boot. You should watch it if you can.