It’s like a fly in your Chardonnay (Republican Freedom Edition)

One thing that a theory that key American institutions continue to be beset by systemic racism while denying that systemic racism exists would predict is that those institutions would strive to make it difficult or impossible to even explore the question of whether key American institutions continue to be best by systemic racism while denying systemic exists.

It’s quite a catch, that catch-22:

In April, Cheryl Harris, a law professor at the University of California, Los Angeles, noticed an uptick in citations of her work. Sort of.

“My inbox started being flooded with very bizarre and rabid emails and voicemails attributing things to me that I’ve never said,” she recalled in a phone interview. “I’ve been in this scholarly business long enough to know that occasionally, somebody may pick up something that you write and take exception to it. But this had nothing to do with anything I had said, actually.”

Harris’ name was appearing in op-eds purporting to explain critical race theory (CRT), a decades-old vein of scholarship that she has contributed to and taught.

Critical race theory studies racism at the systemic level, examining how policies, laws and court decisions can perpetuate racism even if they are ostensibly neutral or fair. Since its emergence in the late 1970s and 1980s, the discipline has expanded to include researchers in sociology, education and public health.

It has lately come under fire by Republican lawmakers who assert critical race theory is un-American and racist, and argue it will further divide the country. Legislators in at least 15 states have introduced measures this session that would prohibit the teaching of critical race theory or related concepts in all publicly funded schools, sometimes including penalties such as dismissal of teachers or defunding of school districts, despite no evidence that it is being taught in any public school.

Freedom’s just another word for nothing left to teach, I guess.

Missouri state Rep. Brian Seitz, a Republican, said in a phone interview that teaching critical race theory in schools would create “another great divide in America.” He introduced a bill that would ban critical race theory from all publicly funded schools, including universities, because it “identifies people or groups of people, entities, or institutions in the United States as inherently, immutably, or systemically sexist, racist, anti-LGBT, bigoted, biased, privileged or oppressed.”

Noncompliance would result in up to 10% of funding being cut until the violation was resolved. The measure died in committee, but Seitz plans to submit a new bill in next year’s session, he said.

Tennessee state Sen. Brian Kelsey also argued that critical race theory will split Americans. “Critical Race Theory creates divisions within classrooms and will cause irreversible damage to our children who hold the future of our great country,” he wrote in an emailed statement to Stateline.

When the Tennessee House and Senate’s anti-critical race theory bills went to conference committee, Kelsey proposed additional amendments, citing his days in law school and claiming to “know [critical race theory] very well.”

The resulting Tennessee bill, which was signed into law last month by Republican Gov. Bill Lee, bars schools from broaching a wide range of topics such as the existence of systemic racism, privilege, oppression and any criticism of meritocracy. It also grants the commissioner of education undefined discretion to withhold state funds from schools found to be in violation of the law.

I’ve taught in American law schools for 30 years. I spent the entire 1990s as both a colleague and friend of Richard Delgado, one of the founders of Critical Race Theory. And I can guarantee you that until it became Fox News’s favorite new chew toy about fifteen minutes ago, the overwhelming majority of law professors had only the vaguest trending toward non-existent idea of what Critical Race Theory even is — “um, something like critical legal studies but about race?” — and CRT was invented in American law schools!

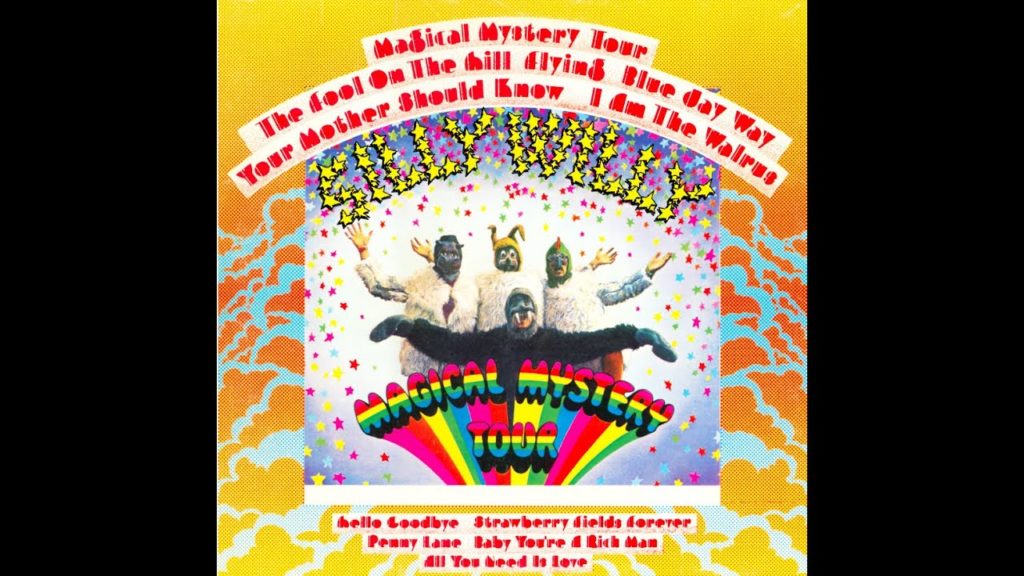

Here’s a little anecdote for you. Every first year law student in America has to take Property law, and like every other first year course Property is almost always taught out of a standard casebook. Over the past 40 years, by far the most popular Property casebook has been this one. It’s 1248 pages long, and since for a variety of reasons Property is the most history-intensive first year law course, there’s a whole lot of highly esoteric historical material in those pages, so that for example if you were to perchance find yourself in 18th century England while needing to break the fee tail encumbering a nobleman’s estate, or you were required to opine on the scintilla juris controversy, or you needed to understand the roots of the concept of a villain in the tenurial land system, either because you were reading King Lear or listening to “I Am the Walrus,” i.e.,

Oswald: Slave, thou hast slain me. Villain, take my purse:

If ever thou wilt thrive, bury my body,

And give the letters which thou find’st about me

To Edmund earl of Gloucester; seek him out

Upon the British party: O, untimely death!

Death!Edgar: I know thee well; a serviceable villain,

As duteous to the vices of thy mistress

As badness would desire.Gloucester: What, is he dead?

EDGAR Sit you down, father; rest you. . . .

this casebook can definitely help you out.

You know what word doesn’t occur once in those 1248 pages?

Slavery.