The Games of 2020

As I’ve written here in the past, I am the very opposite of an avid gamer. Or rather, I play games quite avidly, but I’m never up to date with whatever the community is into. What is Hades? Why is everyone up in arms about Cyberpunk 2077? I have no idea. (OK, I’m kidding about that last one—I love entertainment industry trainwrecks, so I’ve been following every update on the Cyberpunk 2077 debacle; but if they fix the game, there’s no way I’m going to play it.) Anything that requires shooting stuff or hand-eye coordination is out for me, plus my “gaming” computer is a 2016 MacBook Pro, so that limits my options as well. But I do appreciate a good computer game for what it can do with storytelling, puzzles, and interesting mechanics, and I played quite a few games that felt worth talking about in 2020. So this isn’t a best-of list so much as my thoughts about the year’s gaming. Feel free to add you own in the comments.

(Not discussed in this post: more hours than I can count playing Civilization V. I actually got the achievement for winning with all available nations this year, which I don’t think is something to be proud of.)

Creaks (2020)

I’ve been a fan of the Czech game studio Amanita Design since playing their magnificent Machinarium in 2009. That game was a charming point-and-click adventure of the type that hardly gets made anymore, and it distinguished itself with an engaging story, gorgeous hand-drawn animation, clever puzzles, and perhaps most of all, an engrossing and vividly imagined world. In subsequent games over the last decade, Amanita have continually demonstrated a firm grasp of these core qualities, while also feeling free to experiment. Their follow-up to Machinarium, Botanicula (2012), falls somewhere between an adventure game and a walking simulator, all set among the branches of a particularly lively tree. They returned to pure adventure games with Samorost 3 (2016; don’t let the numeral scare you off—the previous Samorost games were more proofs of concept, and this one can be played without knowing their story), and then spun off one of that game’s puzzles into the mini-game Pilgrims (2019), which offers a novel and witty twist on the deck-building mechanic. All are characterized by fully-realized worlds that give depth to even the most familiar puzzle types.

Amanita’s latest game, Creaks, is yet another departure, a more purely puzzle-based game in which you play a young man who discovers a tunnel in his bedroom that leads to a vast, crumbling castle, carved out of the rock of an underground cavern. Moving up and down through the castle’s various environs—libraries, temples, churches, star observatories, laboratories—the player is repeatedly confronted with obstacles, chiefly the creaks of the title, fantasy creatures that include ravenous robotic hounds, floating jellyfish, and menacing humanoid figures with spiky heads. Each one operates according to certain rules, which the player learns and then has to mix and match in subsequent puzzle levels. These rules often operate on the logic of nighttime terrors that informs the game’s entire aesthetic—one way to neutralize the creaks is to shine a light on them, which transforms a hound into a cabinet, a spiky-headed figure into a coat stand. Eventually, a story reveals itself, involving anthropomorphic bird creatures, an enormous monster menacing the castle, and a lot of hubris. But though the characters are as charming and quirky as in any Amanita game, it is mainly scaffolding on which to hang increasingly-challenging puzzles.

It’s a fairly straightforward game, but like all Amanita products, Creaks is elevated by stunning animation and music, and by detailed, witty worldbuilding. The robotic hounds, for example, will happily maul you to death if you get too close, but if you happen to block their path to their favorite sleeping mat, they’ll whine and paw at the obstacle in a winningly pathetic way. And the solution to one of the game’s most challenging puzzles involves placing male and female spiky-headed figures next to each other, causing them to fall in love and ignore you. Similar details—carved busts that chitter and chew gum as they observe our hero, rooms packed with dilapidated sporting equipment or art supplies, an enormous church organ—litter every scene and environ in the castle, and together they make Creaks an engrossing experience, one that is hard to shake once the game is over.

Elsinore (2019)

Hamlet meets Groundhog Day in this social simulator from Golden Glitch Studios. You play the doomed Ophelia, who has a vision of the horrors about to befall her family and the royal court just before being murdered (yes, murdered; no wimpy drowning here). Then Ophelia begins living the days spanning the events of the play over and over again, accumulating information about the castle, its inhabitants, and the royal family’s history. You can follow different characters around and listen in on their conversation, and spill dirty secrets just where they can have the most effect. You can reveal secret crushes, drive multiple people to madness and suicide, hang out with Hamlet Sr.’s ghost, and most gratifyingly, discover the nearly endless variety of ways in which one can bring about the whiny, self-absorbed Hamlet’s death.

It’s once you’ve plumbed the depths of the information you can accumulate and the influence you can have that you start to run into trouble. Ophelia’s goal is to find a way to save everyone at court from their own lies and stupidity, as well as the approaching army about to overrun the castle. At some point you acquire The Book of Fate, which lays out all the different endings you can achieve (which include shuffling off Queen Gertrude so that you can marry Claudius, joining the crew of a pirate queen, and running off to have adventures and canoodle with a gender-swapped Guildenstern). But then the inevitable rewind happens, and you find yourself facing yet another timeline. There are hints of a deeper ending that might allow the player to free Ophelia from her loop, but I got bored trying to find it. The pleasures of Elsinore come from figuring out just how far you can push its story past the limits of the original, and once you’ve charted those boundaries, there’s no avoiding the conclusion that, like a lot of other time loop stories, this one isn’t really about anything.

I found myself comparing Elsinore to Night School Studio’s Oxenfree (2016), another socially-focused game with a time loop at its center. Oxenfree has better graphics and voice acting, so it more easily achieves an emotional atmosphere that Elsinore struggles to match. But even making allowances for those differences, Elsinore just doesn’t have the kind of emotional depth that would justify spending time with its characters, moving through the same story again and again. Once you remove the tragedy from Hamlet, it turns out, what you’re left with is a bunch of very silly people who need to either be rescued from themselves, or helped along the path to destruction, and after a while both of those options begin to pale.

Florence (2018)

More an interactive novel than a game, Florence, by Melbourne-based game studio Mountains, follows its title character, a twentysomething office worker, as she meets and falls in love with a musician named Krish, and as their relationship first deepens and then founders. It’s a short game, maybe half an hour all told, and its puzzles are more in the way of metaphors that help the player to become invested in Florence, and in her and Krish’s relationship. When the two go out on their first date, for example, Florence’s dialogue bubbles appear as puzzle pieces which the player has to assemble. As the date progresses and the connection between Florence and Krish deepens, the puzzles get simpler and take less time to assemble, symbolizing the pair’s growing connection. But later, when Florence and Krish fight, her dialogue bubbles appear as whole pieces, no assembly required, to remind us that words said in anger come more easily. When Krish moves into Florence’s apartment, the player has to decide which of his belongings to place in cupboards and shelving units, and which of Florence’s possessions should go into storage to make room for them. There’s no “right” answer to which belongings to keep and which to store, just a reminder that relationships require accommodation.

It’s a solid concept, and the execution—the hand-drawn animation and particularly the music—do a lot to make it winning. But eventually it’s hard not to notice how generic the story and its characters are. Florence is almost entirely wordless, and a lot of its emotional beats are expressed through visuals—a paintbox given as a gift to Florence, who dreams of being an artist, being buried under pieces of mail and other junk as time passes; a puzzle of Krish and Florence embracing whose pieces drift away as the player tries to put them in their correct places. But one effect of that is that the characters never seem like more than types, and their relationship troubles—Krish is following his dream of becoming a professional musician, while Florence allows her happiness in their relationship to distract her from how dissatisfied she is in other aspects of her life—never develop beyond these over-familiar tropes. Florence is sweet and, especially given its short playing time, extremely winning, but it’s hard to feel invested in its central romance, its breakdown, or its title character’s journey of self-discovery.

Kentucky Route Zero (2013-2020)

I actually played most of Kentucky Route Zero in 2016, when I bought a season pass for the first four acts, plus the promise of a fifth to come. That act, finally delivered this year, is really more of a coda to a story that had already concluded several years ago, with most of its characters—and particularly the hired man, Conway, whose quest to deliver a truck full of furniture kickstarts the entire narrative—having reached either their final destination, or a stopping point from which they’re going to have to reassess their next step, maybe even their entire lives. Anyone expecting some definitive answers to the question of what the Zero—the hidden, circular highway where the lost and dispossessed wash up—actually is won’t find them in this final act (though there is some more information about the game’s setting and characters to be found in the “interludes” that designers Cardboard Computer added to the game for its console release). What you get instead is elegy—officially, for a pair of horses drowned in a flood, but really for Conway and everyone like him, chewed up and swallowed by the rapacious capitalism that is destroying the game’s rural setting.

The release of the final act was thus more of an excuse for me to experience Kentucky Route Zero from the start, and to be amazed all over again at what a tremendous, innovative achievement it is. On almost every level, it does things I hadn’t realized games could do. Visually, the game takes simple polygon animation and not only executes it flawlessly, but combines it with impeccable direction to create a truly unique experience, at once interactive and cinematic. Instead of following the characters in straight lines, the “camera” circles around them, moving through a building (which falls apart in panels around us) when the action moves further into it, and then retreating from it when it’s done. The storytelling is never entirely linear, sometimes jumping into the point of view of an unfamiliar character in an unknown future who is watching security footage of our heroes, other times forcing the player to choose between observing certain characters, while others go off to have their own, unseen adventures that nevertheless affect the plot. In the final act, you abandon the familiar characters entirely to play a cat, who listens in on their conversations but also interacts with shadowy figures—it takes a while to realize that these are ghosts, visible to a feline but not to humans. And the game’s flights of surrealism never fail to strike home—a town bought out by developers whose homes have all been moved, with their inhabitants still in them, to a “Museum of Dwellings”; a brewery staffed by reanimated skeletons who keep paying off their debt to the company even after death; a computer game within the computer game that reveals a missing chunk of the Zero’s history.

At the core of Kentucky Route Zero is a tale of the hollowing out of the American heartland. Its characters are burdened by debt and medical expenses, still bitter about homes foreclosed on, businesses run into the ground, mining accidents that were never accounted for. It’s a familiar premise from a lot of entertainment over the last decade, but where Kentucky Route Zero distinguishes itself is in refusing to pigeonhole its characters or setting. Yes, there are miners and mechanics and truckers and barflys in this game. But there are also artists, academics, explorers, city planners, journalists, performers, and dreamers. The portrait it paints is of a vibrant, modern community, that nevertheless can’t survive the pressures brought to bear on it.

The Procession to Calvary (2020)

Created by independent game designer Joe Richardson, The Procession to Calvary is the game to play if the idea of a Thirty Years War-themed, Monkey Island-style, point and click comedic adventure whose graphics were created by cutting and pasting backgrounds and figures from Renaissance paintings appeals to you. You play a soldier who is dismayed to discover, at the end of a fictionalized but quite familiar dispute, that she’s no longer allowed to slaughter people in the name of god, and who accepts a mission from the game’s Holy Roman Emperor stand-in to assassinate the man he’s recently deposed. Getting to that emperor’s court and gaining access to him is the business of the game, tripping over the rubble of the recent unpleasantness as you go—mutilated knights and commoners, wrecked landscapes, lots of people being tortured, and even a Satanic cult.

As you might imagine from that plot description, Procession is irreverent, occasionally even crass, and like its inspirations (Richardson cites Monty Python on his website) wastes no opportunity to make its characters look venal, cynical, and anachronistically knowing. Combined with the game’s unusual style, it makes for a refreshing and amusing gameplay experience. It’s particularly interesting to observe Richardson’s collage work (he helpfully provides a gallery room where the player can view the original paintings—including, of course, the one that gives the game its title—and spot which element has been ported over from where). Graphics are often the Achilles’ heel of small-budget, independent games, and Richardson’s approach manages to be striking and original, while giving him an excuse to steal from the great masters of history. The game’s soundtrack is equally good at making a virtue out of a necessity—every screen includes a musician or musical group (taken from yet another painting, naturally) who just happen to be playing a different piece of classical music.

A lot of the pleasure of Procession, then, comes from playing a familiar look-take-talk puzzle game (here with an additional option, stab) whose setting, attitude, and appearance are so unfamiliar. But even in a relatively short game (I finished the whole thing in less than three hours, and I’m not a very fast gamer), a certain shallowness eventually becomes apparent. The puzzles, for example, are extremely variable in their originality and cleverness. The best of the lot requires the player to go on a scavenger hunt in the paintings from which Richardson has taken his design elements, but most of the others feel generic for this type of game rather than, as the best Monkey Island puzzles did, emerging from an increasingly tortured development of the game’s central metaphors. One puzzle in particular, in which the game’s heroine has to win a talent contest, has been lifted whole-cloth from Day of the Tentacle. (Also, a personal bugbear of mine: you shouldn’t have to copy text from the screen to be able to solve puzzles in a game like this.) Procession is worth playing for the sheer outrageousness of its concept and the novelty of its graphics, but if you’re looking for a worthy successor to Monkey Island, this isn’t quite it.

Return of the Obra Dinn (2018) / Papers, Please (2013)

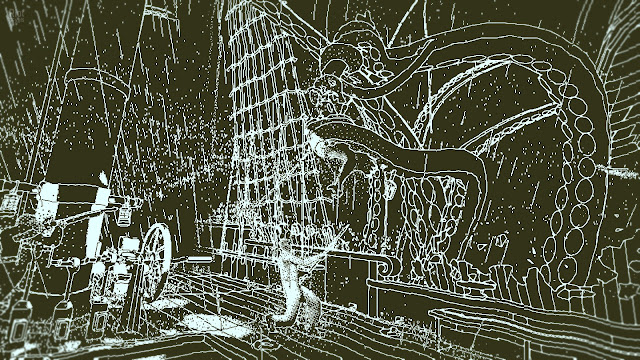

The first game I played in 2020 was Lucas Pope’s eerie mystery Return of the Obra Dinn. Drawn in a deliberately retro style—black and white pixelated animation—that is nevertheless gorgeous to look at, Obra Dinn puts you in the point of view of a 19th century insurance investigator sent to explore the titular ship, which has drifted into English waters years after having been declared lost at sea. Armed with a clock that allows you to witness the dying moments of the ship’s crew and passengers, the player travels backwards from the last of these deaths to the first, unraveling a tale that ends up involving greed, betrayal, and a hell of a lot of sea monsters. It was a perfect game to play in late winter, with each step through the ship exposing yet another bit of horror, making for a tense, involving gameplay experience.

Having loved Obra Dinn so much, I finally got around to playing Pope’s first, breakout game, Papers, Please. In this game, you play a newly-promoted border inspector in a fictional 1980s Soviet-style country. Each day, the rules about who to let in, what documents they need to have, and who to look out for change, and you need to keep abreast of all of them while processing as many people as possible. It may sound tedious, but there’s a palpable urgency to it—your character gets paid according to the number of people they process, and docked money for incorrect decisions; meanwhile, the rent and heating bill need to be paid. The game very quickly places moral quandaries before the player—do you let this mother, desperate to be reunited with her son, into the country even though her documents are insufficient? Do you accept this bribe from a drug smuggler? And all the while in the background, an uprising is brewing, which your character can choose to aid or to expose.

The thing I find striking about both Pope games is how they are both, fundamentally, very familiar types of puzzles. Obra Dinn is a logic puzzle, in which the player has to use contextual clues to identify each of the ship’s passengers and the manner of their death. Papers is yet another variant on the game we’ve been playing since at least Tapper, in which the player has to perform increasingly complicated tasks at increasing speed. Pope overlays these puzzles with strong narrative and intriguing worldbuilding to make something more out of them—in Obra Dinn, a neo-Lovecraftian tragedy of racism and colonial hubris; in Papers, an illustration of the compromises necessary to survive under an autocratic regime. It’s an approach that pays tremendous dividends, resulting in games that are both engrossing and thought-provoking.

Quern: Undying Thoughts (2016)

The best way to describe Quern is Myst methadone. If, like me, you imprinted at a young age on Cyan’s groundbreaking exploration game (and its even more magnificent sequel, Riven), then Quern is… well, not exactly the game for you, but it’ll do till one comes along. As in Myst, you play a nameless first person player who is compelled to explore a mysterious, beautifully animated island littered with challenging environmental puzzles and diary excerpts that hint at a dramatic conflict in which you’ve become embroiled. Just about every element you might fondly remember from Myst is featured here: numbering systems, codes, movable bridges, rotating rooms, animated rides from one part of the island to another, and most of all puzzles that require you to work out the mechanical systems constructed by the island’s former inhabitant.

Despite clearly being the work of genuine Myst fans—Hungarian-based designers Zadbox Entertainment were a group of gamers who crowdfunded the game on Kickstarter with the explicit selling point of having been inspired by Myst—Quern lacks a certain je ne sais quoi. Its puzzles end up feeling just that little bit clunkier and more contrived than they should be, its story and characters less involving. (It doesn’t help that what should be the game’s big leveling up moment, when you finally make your way into the island’s backstage area, instead delivers more of the same type of puzzles.) That still makes for an engaging gameplay experience, especially if you’ve been looking for something Myst-esque to occupy your time. But it feels telling that Quern was published in the same year as The Witness. That game ruthlessly dismantled the type of story and puzzles that Quern merely repeats, and for all of Quern‘s technical accomplishments, it feels inessential in comparison.