Erik Visits an American Grave, Part 696

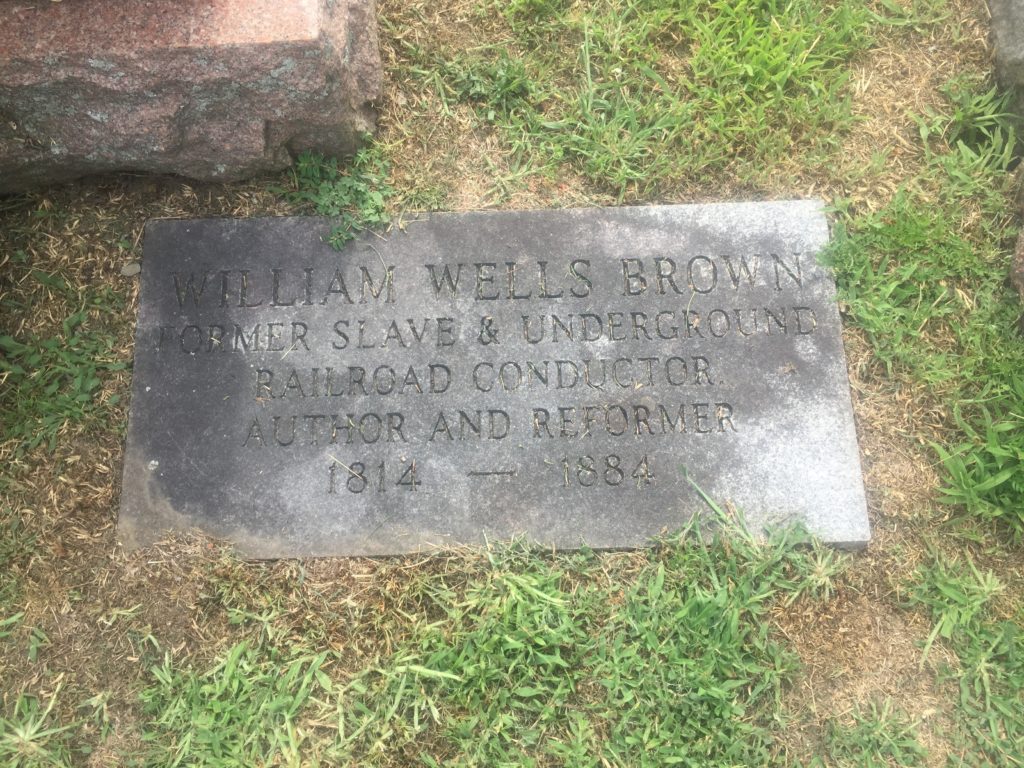

This is the grave of William Wells Brown.

Brown was born into slavery in approximately 1814 to a planter in Kentucky. His mother was a slave woman who had seven children by seven different men, largely probably because of sexual assault or other unequal sexual relationships. Brown’s father was white but not his mother’s master. He actually acknowledged the child was his and asked the owner not to sell the boy and his mother. The owner agreed but then of course reneged. And Brown was sold several times by the time he was 20. In 1834, he escaped. He was hired out by his master in 1833 to work on steamboats in St. Louis. This was one of the few scenarios where escape was actually a reasonable possibility. That his story here isn’t that different from that of Frederick Douglass demonstrates this. In cities like St. Louis (or Baltimore in the case of Douglass), slaves were often sold out or even told to work on their own and just pay the master a portion of the wage. Control wasn’t that intense and being near water and people moving north and south, slave movement into free territory was at least possible. Not that it was easy or without risk. In 1833, Brown tried to escape, with his mother, and was caught while in Illinois. But the next year, he did escape, fleeing from a steamboat he was working on when it docked in Cincinnati.

This time Brown was not caught. Instead, he met the anti-slavery Quakers in southern Ohio. The name of the man–Wells Brown. He dropped his slave last name and took his. They helped teach him to read and write. Soon Elijah Lovejoy hired Brown to work on his abolitionist newspaper operating in Alton, Illinois, just over the Missouri River. In 1837, pro-slavery forces would murder Lovejoy for this. By this time though, Brown had married and was living in Buffalo. Here he did what he was trained to do–working on ships. This was the steamer age and there was plenty of work for an experienced hand like Brown. But he was also helping ferry escaped slaves to Canada. He at least claimed that between March and December of 1842, he helped 69 people get to Canada. No reason not to believe him. He started speaking out about the horrors of slavery and organizing anti-slavery societies in New York. He also did some organizing in the temperance movement in Buffalo. He rose rapidly in the abolitionist movement after 1843. That year, there were two big abolitionist conventions in his new home town and Brown shone in both. He met Frederick Douglass and Charles Lenox Remond there and soon joined them as leading speakers on the horrors of slavery. But even doing this in the North was fraught with danger. Sometimes, he would arrive in town to give a speech and be denied lodging because of his race. In 1844, he went to East Aurora, New York to give a speech. While doing so, whites started pelting him with eggs and rotten food.

The real market for abolitionist speakers was not in the North. It was in Europe, especially England. So it was not surprisingly that in 1849, Brown went with his two daughters (he was estranged from his wife by this time) for a tour of England. He was a popular speaker and an excellent musician, which he integrated into his abolitionist work. While overseas, Congress passed the Fugitive Slave Act. That meant Brown could easily be returned to slavery. So he refused to return to the U.S. In fact, he stayed in Europe until 1854 and did not return until his English supporters bought his freedom from his ex-master. While there, he attended the International Peace Conference in Paris in 1849, an attempt to get people from various countries to talk about how to create peace. Headed by Victor Hugo, it’s a pioneering moment in the global cooperation movement. Brown went there and openly confronted American slaveholders who were also there about their hypocrisy and cruelty.

The main reason Brown is remembered today is the book he wrote while in England. Clotel; or, The President’s Daughter: A Narrative of Slave Life in the United States is a novel he published in 1853. The book went straight to the heart of American hypocrisy. It’s topic was two fictional slave daughters of Thomas Jefferson. Of course the rumors that Jefferson had sired children from Sally Hemings was long rumored, although not then confirmed. It is also believed to be the first novel published by a Black American. Dealing with the reality of forced interracial sex and the problems of mixed-race Black Americans, it is a tough look at taboo issues, especially for the era. Contemporary scholars have noted that the real tragic stories in the book are nearly white slaves who could possibly pass. Maybe that’s true, but it also represents himself so it seems like fairly weak tea to me. It was not his first book–that was his slave narrative of 1847, Narrative of William W. Brown, a Fugitive Slave. It did quite well, not selling quite at the level of Douglass’ Autobiography but not too far off. He lambasted the un-Christian values of his master in it. He continued writing on his return to the U.S., including probably the first published play by a Black American, The Escape; or, A Leap for Freedom, from 1858.

When Brown returned to the U.S., he continued his work, being a popular abolitionist speaker in the northeast. He was close to William Lloyd Garrison and believed that abolitionists should avoid electoral politics so poisoned by slavery. He also started to give up on America, calling for emigration to Haiti, where Black people could live without white domination. During the Civil War, he kept writing and recruited Black Americans to volunteer for the war. He also continued to write after the war, including early histories of Black America, some of the first. In the end, while Douglass is the more famous abolitionist and has the most famous slave narrative, Brown was the real pioneer in the history of Black writing in America. His work is today anthologized in the Library of America. His last book, 1880’s My Southern Home: or, The South and Its People, explored his travels South after the Civil War and relationships between the races. He supported himself though by engaging in homeopathic medicine, opening a clinic in Boston. He died in Boston in 1884, at the age of 70.

William Wells Brown is buried in Cambridge Cemetery, Cambridge, Massachusetts.

If you would like this series to visit more abolitionists, you can donate to cover the required expenses here. Charles Lenox Remond is in Salem, Massachusetts and Levi Coffin is in Cincinnati. Previous posts in this series are archived here.