This Day in Labor History: July 19, 1881

On July 19, 1881, Black laundry workers in Atlanta formed the Washing Society to demand labor rights. This remarkable moment shows how Black workers continued their struggle for freedom after the end of Reconstruction and how women led that struggle.

The post-Civil War period was not great for the now former slaves. They were released from slavery into….basically nothing but not slavery. Everything else was effectively just as bad. The former slaves certainly had their own ideas about the economy, particularly around land ownership and subsistence farming, but that didn’t fit white conceptions of Black labor, north or south. With the failures of Reconstruction in the face of white violence or indifference, there were few economic options for Black people. Those who could left the plantations for the cities. Places such as Memphis, New Orleans, and Atlanta saw enormous influxes of Black people. But there weren’t great economic opportunities there either. For women, working as a laundress was one of the only options.

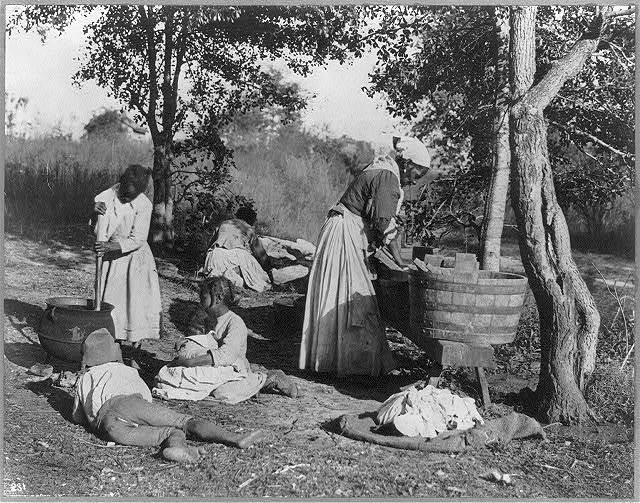

Black women made up half the Black workforce in Atlanta. A full 98 percent of these women worked as domestics in some form or another. They started working in their teens or even earlier. If they lived long enough, they worked until they were 65 or so, but most didn’t make it that long. Of all the forms of domestic labor, laundry was the most common. And it was hard, hot work, with lots of opportunities to burn yourself, not to mention the sheer brutal labor of scrubbing day after day, week after week, year after year. It was hot and it was heavy. Hauling water only made it worse. It only got harder over time. The rise of mass-manufactured clothing and middle-class standards of cleanliness meant that people had more clothing and they changed it more often so there was more laundry per household. For all of this work, they made $4 to $8 a month, far below poverty wages.

In the summer of 1881, Atlanta was hosting the International Cotton Exposition. This was a fair intended by the city’s “New South” promoter Henry Grady to show how far the city had advanced from slavery. A docile work force without slavery was part of the image he and others wanted to promote. But the laundry workers had different ideas. On July 19, twenty laundresses and a few men met and decided to form the Washing Society and organize their fellow workers for a strike to demand higher wages. They did have one advantage. Unlike the domestics who worked in white homes, this was all outsourced to Black women’s homes. So they were independent on a daily basis, not laboring under the eyes of whites. They could form such an organization.

These women weren’t doing out of thin air either. Many of these women had participated in the fight for freedom during the Civil War and Reconstruction. Just because Reconstruction had ended in defeat for justice in 1877 doesn’t mean that the fight didn’t continue. This was the next stage of two decades of organizing and fighting since the beginning of the Civil War. Moreover, in 1880, Black Republicans had taken over the Georgia Republican Party and had spoken out publicly against lynching. This was a period of militant organizing in Atlanta.

The Washing Society grew fast. Within three weeks, there were 3,000 members. There weren’t too many white laundresses, but they were welcome as well and many of them joined. They organized door to door. While many of their fellow laundresses wanted to join, there were reports of intimidation of those who did not. It’s hard to know what that even means given the media at the time, but these women were certainly not going by white Victorian era notions of femininity. They had a demand of $1 per dozen pounds of laundry with a mechanism to actually get paid since it was by the individual customer without any oversight. With help from the city’s Black ministers, they went on strike. This wasn’t the first time Black domestic workers in the South had gone on strike after the Civil War. We know of at least brief actions in Jackson in 1866 and Galveston in 1877.

The local white establishment was furious. This was a slap in the face to Grady and others with their self-mythologizing about post-Reconstruction Atlanta. With the newspapers calling them the “Washing Amazons,” cops started arresting strikers and fining them. The city council proposed that any washerwoman who joined any collective organization had to pay $25 to the city per year. They agreed to pay the fee rather than give up, writing to the mayor:

“We, the members of our society, are determined to stand our pledge and make extra charges for washing, and we have agreed, and are willing to pay $25 or $50 for licenses as a protection so we can control the washing for the city. We … will do it before we will be defeated, and then we will have full control of the city’s washing at our own prices. … We mean business this week or no washing.”

This only led to more striking among the Black work force. Other workers–cooks, maids, nurses–began demanding higher wages. There was another strike among hotel workers. The city council caved and rescinded the $25 fee the next day.

The workers didn’t exactly win the strike. The intense retaliation did affect the strikers. There was no real way available to force $1 a pound from individual customers. But their wages probably did go up after this, if only to keep them working. It also demonstrated to everyone that Black women were not going to be the docile workers Grady imagined. This was a working class movement ready to show both racial and class defiance as Jim Crow settled in on the city. We also have no information on what happened to the Washing Society after the strike ended. But this was the largest strike among Black workers in Atlanta in the nineteenth century.

I borrowed from Tera Hunter’s 1997 book, To ‘Joy My Freedom: Southern Black Women’s Lives and Labors after the Civil War to write this post.

This is the 363rd post in this series. Previous posts are archived here.