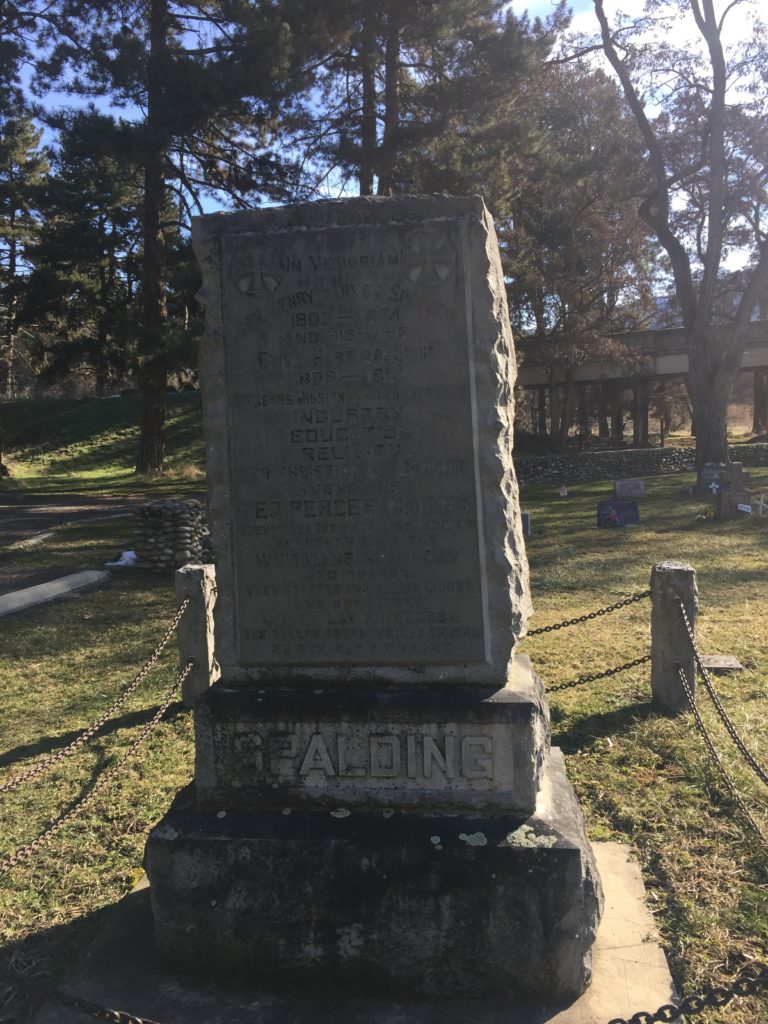

Erik Visits an American Grave, Part 654

This is the grave of Henry and Eliza Spalding.

Henry Spalding was born in 1803 in Bath, New York. He ended up out in Ohio and went to college a bit later in life than most, graduating from Western Reserve College (today Case Western) in Cleveland in 1833. He then trained for the ministry, graduating from Lane Theological Seminary in 1837. That was Lyman Beecher‘s influential minister college in Cincinnati. Spalding was there in its early controversial years. See, because it was Beecher’s version of Presbyterianism, it attracted a lot of abolitionists. But that was an untouchable topic in this extremely racist city, so administrators put a clampdown on discussing it, which led to a huge blowup in the college and many students leaving. But I don’t really know if Spalding was involved.

In 1830, Spalding began corresponding by letter with a woman named Eliza Hart, who was probably also born in 1803. They had a mutual friend who wanted to set them up. When they met in person a year later, they fell in love and were married in Hudson, New York in 1833. When Spalding was given an assignment by the American Board of Commissioners for Foreign Relations to run a mission with the Nez Perce tribe in what would become Oregon and Idaho in 1836, Eliza agreed to go with him.

The Spaldings really were way out past the frontier of Euro-American settlement. Life had changed radically for the Nez Perce since they first dealt with the Lewis and Clark Expedition in 1805, but the idea that they would soon be vanquished was not on their minds in 1836. There were only a very few white missionaries in this region. Initially, they were to be sent to a safer mission with the Osage in Missouri, a people already heavily displaced by whites. But Henry Spalding knew Narcissa Whitman from a church they both attended in Prattsburgh, New York in the 1820s. She introduced him to her husband Marcus as they were preparing to go to what is today southeast Washington. They convinced him to join them and Eliza agreed to it. Traveling across the Plains with the Whitmans, they joined up with some fur traders to the Wind River Mountains of Wyoming. From there, they were on their own. There were a couple of forts out there, but that’s a harrowing journey in 1836. After going to Fort Vancouver to get supplies for their new mission, they headed back up the Columbia. The Spaldings started their mission near modern-day Lapwai, Idaho, with the Nez Perce. Eliza described their new home:

“3 springs of excellent water near, one enclosed in our door yard, for by and by, we have a rude fence around the house, made by the Indians who appear to be delighted to be employed about something that will benefit us. I think I can truly say that we are satisfied and happy with our employment and situation. As to the comforts and necessaries of life, we have an abundance.”

People in Idaho love to note that this was the first white home in their future state, as if that was something to be proud of. But Pacific Northwest whites love, love, love talking about the pioneer heritage without any attention paid to what that meant to Native populations.

The Spaldings got along well enough with the Nez Perce compared to some missionaries with Native communities, including the Whitmans, massacred in 1847 by the Cayuse. But it’s not as if Henry especially was exactly pro-Indian culture. They were there to convert souls, bring civilization, and crush Nez Perce culture. They were able to baptize some leaders, which really usually meant something a lot different to the missionaries than it did to those being baptized. Some did become real converts. And the Spaldings would use those converts as force against Nez Perce near the mission who did not follow their ways. These were tremendously inflexible people who brought their Protestant values with them. When Spalding found out about polygamy, common enough in Nez Perce culture, he would have the perpetrators whipped or even worse, have them whip each other, a classic move of the slave power that he hated when it applied to Black people. But like many abolitionists, there was a pretty big divide in his mind between chattel slavery and the Native cultures that needed to change or die. He did all he could to stamp out drinking and gambling as well. Eliza attempted to mediate between Henry and the Nez Perce and gained their respect much more than he ever did. He was also a difficult man with his other missionaries. The Whitmans turned on him and he was even fired by the American Board in 1842, though he refused to leave the mission and was eventually reinstated.

When the Whitmans were massacred, the Spaldings’ daughter Eliza was at their mission school. But the Cayuse didn’t target the children and she was fine. They were held in a sort of protective custody for a month and then got out of there and headed down the Columbia to the growing American settlement of Oregon City until things cooled down.

Once Spalding was safe, he wanted to massacre some Indians in revenge and pledge missionary money to raise a force against them. He also hated Catholics with a deep passion and blamed their influence on the Cayuse for the massacre; claiming Catholics whipped up Native violence against Protestants was a long-standing belief among American missionaries. The Missionary Board gave up on the Nez Perce mission after the massacre. The Spaldings stayed in the Willamette Valley of Oregon Territory. Eliza took a job as the first teacher of Tualatin Academy, which became Pacific University in Forest Grove, Oregon. They then moved into the southern Willamette Valley and farmed near Brownsville, today primarily known for hosting Oregon’s largest festival of bad Nashville douchebro country music every year. He got a job as Oregon Territory’s schools commissioner in 1850 and held that for five years.

In 1851, Eliza Spalding died. In 1853, he remarried, to Rachel Smith, the sister-in-law of another missionary. Spalding’s crankiness did not help secure stable employment and by the late 1850s, he was pretty much reliant on churches sponsoring him for work. He also worked the U.S. Indian Affairs department. In 1859, much to his delight. that connection sent him back to the Nez Perce. He restarted the Lapwai mission in 1862. But he struggled to keep it going. Of course, he had a good target for his failures–the Catholics. He also blamed the federal government for not supporting his mission enough and even took the long, now less arduous trip thanks to the Transcontinental Railroad back to Washington in 1871 to testify before Congress about this. He returned later in 1871, started a school for Nez Perce children, and then died in 1874. Three years later, the Nez Perce would be driven from their land by the genocidal campaigns of the U.S. military.

Henry and Eliza Spalding are buried at Lapwai Mission Cemetery, Lapwai, Idaho. Eliza was moved there from Brownsville sometime in the 1910s.

If you would like this series to visit other American missionaries, you can donate to cover the required expenses here. Lottie Moon is in Crewe, Virginia and E. Stanley Jones is in Baltimore. Previous posts in this series are archived here.