Erik Visits an (Non-) American Grave, Part 634

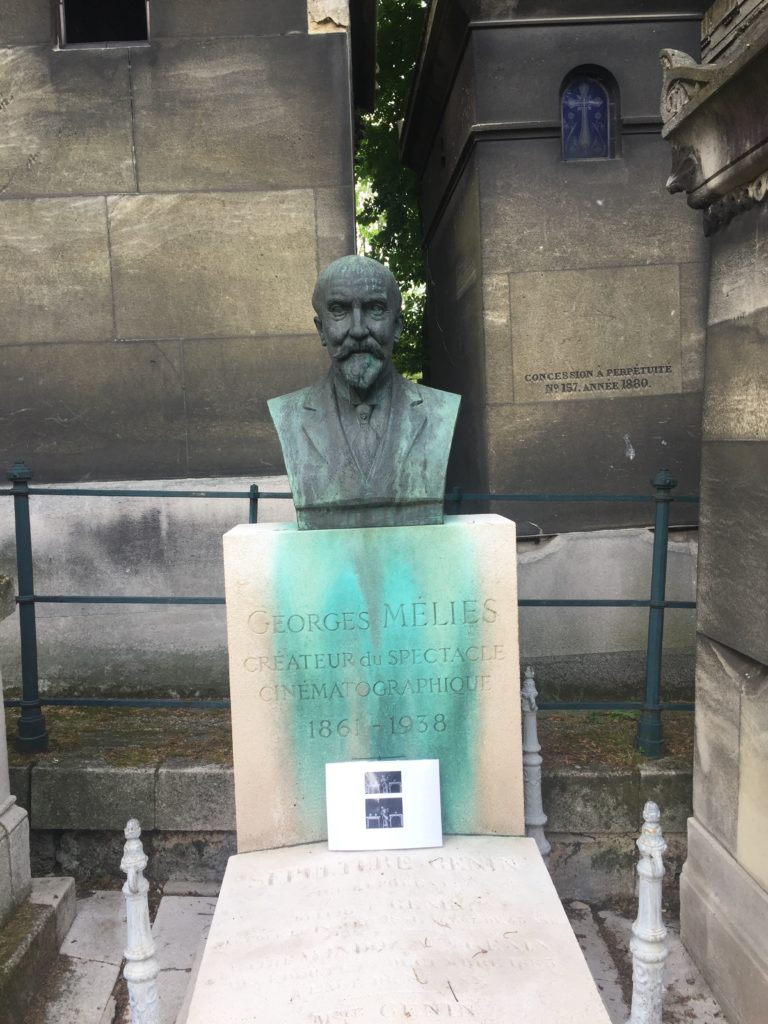

This is the grave of Georges Méliès.

Born in 1861 in Paris, Méliès was born into a bootmaking family. His mother was Dutch and her father had been the official bootmaker of the Dutch court. His father was a bootmaker as well, though not working in any kind royal court evidently. The family became pretty wealthy in this business and Georges grew up as a rich kid. He was a pretty good student but one distracted by his invention of games and his interest in theatre. He was making his own cardboard marionettes by the time he was 10. He went to school until 1880, graduated, and entered the family business.

But his only real interests were magic, special effects, and performance. He spent time in London working for the family business, but mostly hanging out at magic shows and other performances. He came back from London wanting to go into the performing arts full time. His father was outraged and refused to support such frivolity. But in 1888, his father retired and left it to his sons. Georges sold his share of the business to his brothers. He had married a fairly wealthy woman and the dowry combined with the money from selling his stake in the boot business allowed him to purchase a theater. But it was old and dilapidated and didn’t really do all that well. Méliès was still a dreamer, but now an aging one and one without much of a financial future.

Near the end of 1895, Méliès saw the work of the legendary Lumiere brothers and their cinematograph, the precursor to cinema. He was amazed. He wanted to buy one of their projectors immediately, but they declined his offer. So he set out to find someone who could make something similar. He traveled to London and bought one off the English cinema pioneer Robert Paul. By April 1896, Méliès’ theatre was showing some kind of quasi-movie every day. More importantly, he started using his incredible creativity to create his own movies. He was technically inventive and a genius. As cameras improved, which they did very rapidly after 1896, he upgraded as well. And his films became probably the first true art of the entire genre of cinema.

What made Méliès so brilliant is that he saw the cinema and realized it could be about the fantastic, not just the daily life of people, as valuable as that is too. Moreover, he was deeply invested in special effects and had a great sense of humor. All of this made him the first real filmmaker. And he pumped out those films, as did so many early filmmakers. People disappeared, demons and angels appear in the sky, people remove their own head. He was one of the first people to try and move the camera during shooting. His theatre soon was just a film theatre, showing his own material. Mostly, he worked in his inventive mind but he would do anything, from early “stag” films that showed a woman not wearing much in the way of clothing to early advertisements.

Méliès’ real breakthrough came with A Trip to the Moon, in 1902. Borrowing from Jules Verne and H.G. Wells, Méliès famous scene of a spaceship hitting the moon in the eye became, along with the gun pointing at the screen in The Great Train Robbery, the first iconic scene in film history. It also made him an international phenomenon. Of course, in an era without copyright law, people just stole his film and made their own money on it, including Thomas Edison. Méliès traveled to New York to fight against this, which didn’t hurt his attempt to promote himself, in any case. He continued making hugely popular fantastic films such as 1903’s The Kingdom of the Fairies and 1904’s The Impossible Voyage. Méliès and Edison kept fighting each other too, with Edison once suing the French director over a copyright violation.

The sad thing for Méliès though is that film was moving so fast that by 1907, his style was already becoming dated. He struggled to adjust. Newer films were either second-rate versions of what he had already done or half-hearted attempts to embrace new genres, such as crime-based films. In 1908, he and Edison patched up their problems enough that Méliès joined the Americans’ new international film syndicate, which was far more about controlling the market and making Edison money than anything artistic in nature. He produced one of his favorite films in 1908. Titled Humanity Through the Ages, it was a look at the downfall of humans from the Garden of Eden to the present. But by 1910, Méliès was making very few films. He started losing control of the power to edit his own movies by 1912, with the conglomerate concerned that their length meant that no one would go see them. That year, he went to Tahiti with his entire family to make films. It was a disaster. It was incredibly expensive and and much of the footage was damaged and unusable by the time it arrived in New York for production. Méliès was bankrupt.

Méliès became increasingly bitter. His studio was commandeered by the French government as a hospital during World War I. Then his theatre was torn down to expand the Boulevard Haussmann. In 1923, furious, he burned all his negatives.

By 1925, Méliès was broke, divorced from his wealthy wife and then remarried to his very unwealthy mistress, and working in a toy store to make ends meet. But film had become such a major art form by then that the French, already international leaders in the industry, started looking back at the past and remember and save it. Journalists started come calling for interviews. In 1926, a publisher asked him to write a memoir. And then in 1929, he received a retrospective of his work. Many of him films were lost due to his fire, but because he was so popular, a couple hundred still existed. In 1931, Louis Lumière presented him with the Chevalier de la Légion d’honneur. This was all great, but he still had no money and was working 14 hour days, usually 7 days a week, just to eat. He was old too. But in 1932, the French film industry’s retirement home made a place for Méliès. He started to meet a new generation of filmmakers who loved him, people such as Georges Franju and Henri Langlois. They set him up as the first conservator of the French film archive that became the Cinémathèque Française. He had to be admitted to the hospital at the end of 1937 and died early in 1938, of cancer at the age of 76. Langlois and Franju were among the last people to see him.

Méliès was of course the subject of Martin Scorsese’s brilliant 2011 film, Hugo. It always amuses that people see Scorsese as this guy who only does the same mafia film over and over again. This is a total disconnect from reality. Not only does Scorsese have nearly as many films about religious devotion as he does about the mob (The Last Temptation of Christ, Kundun, Silence), he also has everything ranging from The Age of Innocence to The King of Comedy to Hugo. Few filmmakers range as far and wide as Scorsese and Hugo was just really great, with very good work by Ben Kingsley as Méliès.

Georges Méliès is buried in Père Lachaise Cemetery, Paris, France. I am sad to say that this is the last of my French graves from my trip a couple of years ago. Let’s watch some Méliès films.

If you would like this series to visit other pioneers of cinema, this time in the United States, you can donate to cover the required expenses here. The reason this is the first grave post in a week is that I was on a reader-funded grave trip over the weekend, where I picked up only about 35 graves! The location will soon be revealed! Edwin S. Porter, who directed The Great Train Robbery, is in Somerset, Pennsylvania and Wallace McCutcheon, who directed the 1904 film The Suburbanite, is in West Long Branch, New Jersey. Previous posts in this series are archived here.