This Day in Labor History: January 9, 1973

On January 9, 1973, 2,000 workers employed by the Coronation Brick & Tile Factory, outside of Durban, South Africa, went on strike. This was the first major resistance to the South African apartheid state since the sentencing of Nelson Mandela in 1964 and a key moment in the history of the South African freedom struggle.

Durban had long been a center of worker resistance in South Africa, especially because of the longshoremen on the docks there, who, despite their existence in a racially oppressive state, met and talked to workers from the around the world. Going back to the 1920s, black workers there had tried to organize themselves into unions that was part of the larger resistance to white domination. It was hard going and so many of the unionists were also part of the African National Congress and other political organizations that the state banned in the 1960s, making any unionism precarious to nonexistent. The one exception was the dockworkers, who managed limited strikes in 1969, 1971, and 1972. These strikers were repressed and those fired forced to leave the city, for they could not live there without a job. And yet, pay raises resulted. In the months before the 1973 strike, the dockworkers were organizing themselves, making demands on the state, and showing up en masse for hearings on dock wages, where they had white allies make official statements for them, as they could not do so themselves. So the Durban workers were unorganized and unions largely repressed, but there was some significant leadership and inspiration coming from the docks.

The strike started in January, with the brick and tile workers demanding a wage increase of slightly more than double their current wage. It came up pretty much out of nowhere, with rumors of it only in the few days before. The employers had created a flyer just the day before that said any talk of unionism was nothing but work by communist agitators. But that was the extent of the response when the workers walked off the job. A grudging settlement was made a few days later, but by that time, the strike had grown to something far beyond just this one factory. There’s also evidence that the brick and tile workers were influenced by the actions of the dockworkers, who told reporters that they had been following what the stevedores were up to and their fight.

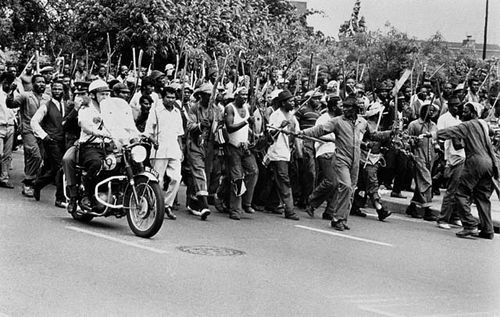

On January 10, a transport firm had a strike. The next day, a tea packing plant. Even Afrikaner papers reported on this relatively favorably, noting the terrible low wages and that there was no evidence any of this was coordinated by outside agitators. By January 25, workers were striking all over the city. A large textile manufacturer saw its workers strike for another doubling of the wage and by the time that was settled, even more workers were striking at other related operations. Municipal workers went off the job at the end of the month and stayed out until February 8. The strikes were continuing to spread at that time, but after the municipal workers came back to work, they slowly wound down elsewhere. The government was shocked by this sudden resurgence of activism and mostly gave in to workers’ immediate economic demands. There were sporadic strikes in Durban throughout the year though.

More importantly, these strikes revived the strong tradition of unionism in Durban and other areas of South Africa. The government tried to claim that outside agitators and communists were responsible, but it really didn’t fly, even in racist South Africa, because there was just no evidence for the assertion. Even the apartheid police said they found no evidence of the accusation. The real reason the strike spread is because the workers were really, really poor. South African blacks were paid a fraction of what whites made. Wages were not going up and the cost of living was rising steadily. Already impoverished and hard-working laborers were getting desperate. They took matters in their hands, even though they had lost their own unions in the previous years.

After 1973, union activity became a much larger part of South African life, with the unions often playing leadership roles in the fight against apartheid. The government allowed black unions to be registered as official organizations for the first time since 1956. The Native Labour Regulations Act of 1973 allowed workers to strike, in a limited fashion, and created committees that could negotiate, albeit only around very trivial manners, between workers and employers. The Trade Union Advisory Co-Coordinating Committee was also founded in 1973 to move this unionism forward. Major unions formed such as the Metal and Allied Workers Union, the Chemical Workers Industrial Union, and the Transport and General Workers Union. These organizations became stronger over time. In 1979, the Federation of South African Trade Unions formed and then in 1983, that was followed by the Congress of South African Trade Unions. These large labor organizations led the fight against the apartheid state and helped bring down that horrendous government in 1994. It is worth noting as well that in almost no cases did the nation’s white unions show any solidarity with the black workers through any of this long fight.

Check out Peter Cole’s book, Dockworker Power: Race and Activism in Durban and the San Francisco Bay Area, for more on how dockworkers in Durban led the labor struggle in South Africa. In it, he makes a compelling case for the dockworkers influence here, which has been ignored by previous historians.

This is the 342nd post in this series. Previous posts are archived here.