LGM Review of Books: Jeremy Milloy, Blood, Sweat, and Fear: Violence at Work in the North American Auto Industry, 1960-80

In our current public conversation about jobs, too often the media and the public point back to the era of the unionized factory job as the golden age. In one way, it was. The jobs paid well and had great benefits, won by unions after hard struggle and strikes. Today, that’s a dream for many American workers.

But the more you explore the time period in which workers lived through these jobs, the more you realize that those wages and benefits covered up a really terrible life. Those “good jobs” were never actually good jobs. They were terrible. Fordism turned workers into machines. The unions managed to gain something in return, but it was a constant battle on the shop floor between workers and foremen. The job was sheer drudgery, day after day, month after month, year after year. Yeah, you might be able to send your kid to college and buy a fishing cabin, but you paid a heck of a price for it, outside of money.

The later rejection of this work and life is personified in the 1972 Lordstown strike, when a tremendously young workforce walked off the job against both GM and United Auto Workers leadership in Detroit, rejecting the drudgery, the speedup, the collaboration of the union in the diminution of their worklife, and the general crappiness of the work. Their demands were vague outside of hiring a bunch of people back, but their anger was real. The “Lordstown Syndrome” got the attention of commenters nationwide. Maybe something different was possible for workers, but for the nation, this seems to have appeared out of nowhere. And then the 1973 recession began, the economy received a series of shocks, jobs went overseas, factories shut down, and no new tomorrow seemed possible for workers except for unemployment, desperation, and poverty.

It’s true enough that Lordstown did shock the nation, including union leadership. But further scholarship suggests it should not and that in fact the workplace was horrible in these factories. This is the story Jeremy Milloy tells in his 2017 book Blood, Sweat, and Fear. Looking at auto plants in Detroit and across the border in Windsor, Ontario, Milloy details a whole history of murderous violence in unionized auto plants. He shows that even in unionized factories, conditions were horrible and sent people over the edge into violence. That American work culture was infused with hypermasculinity contributed to these problems. And while Canadian labor relations were somewhat less hostile than in the U.S. and therefore violence less common there, it was still a problem. Looking specifically at Chrysler plants, Milloy convincing presents a nightmare that should shake us out of any belief the past was better than today.

Despite the conventional wisdom, the 1950s was not a time when companies accepted unions. What had happened was that unions were strong enough that companies had to make public statements about how they accepted unions. But they hated organized labor with great passion and that very much included Chrysler. Beginning in the late 50s, Chrysler started transforming its workplaces in ways that would lead the way into the future. It took away the last remaining ideas of skilled work and worker control over work processes, placing greater pressure on workers every day to increase production, using foremen to drive workers to the point of exhaustion, desperation, and violence. They started hiring more African-American workers at the same time, which helped integrate the workplaces, but also placed them at the bottom of the seniority list and thus both drove them harder than anyone else and helped stew racial tension on the shopfloor. And firing lots of increasingly interchangeable labor helped maintain greater control too. The UAW basically acquiesced to all of this, not seeing many good options.

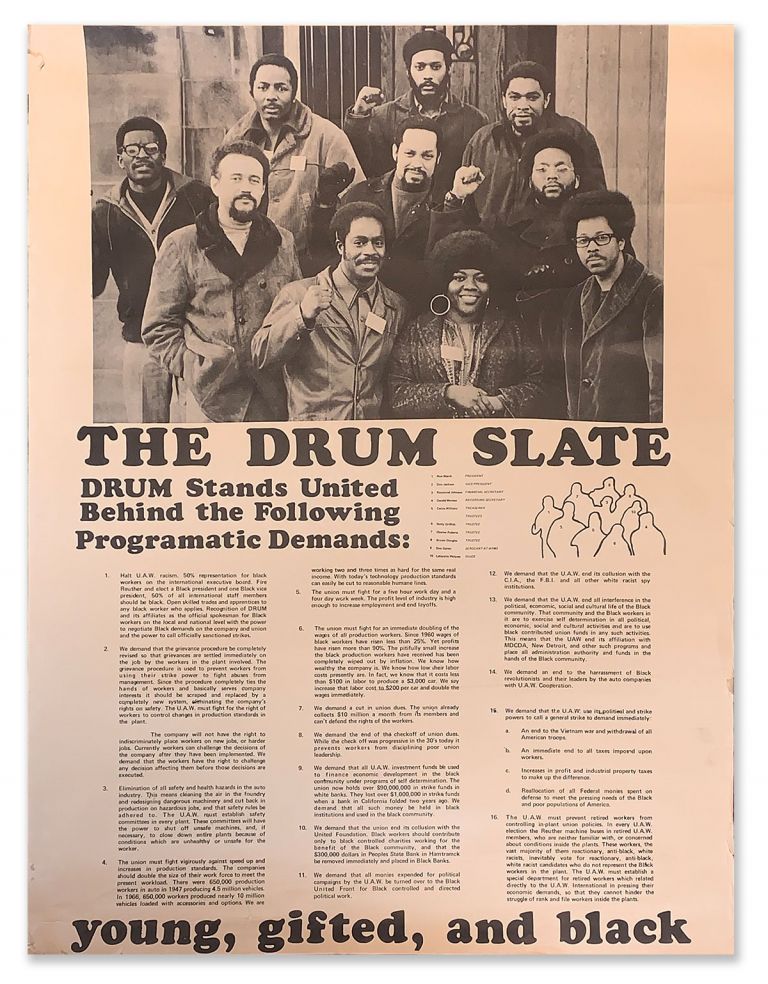

After 1965, these pressures combined with larger societal changes to start leading violence to become a routine occurrence in factories, especially Dodge Main in Detroit. Some of this was related to larger issues. 1967 saw the biggest riot in Detroit during that era of major urban riots. The Dodge Revolutionary Union Movement (DRUM) built on black power to demand violent revolutionary change within the plant. But Milloy also convincingly shows that chalking up to outside forces is both an easy way out and largely wrong. Chrysler instituting greater control on the shop floor and speeding up work both divided workers and drove them into the ground with increased workplace injuries and deaths. Some foremen and other supervisors would act violently toward workers; far more simply intimidated them on a daily basis.

Workers began responding by threatening violence against supervisors. One worker hit a supervisor over the head with a big piece of metal, for instance. Much of the violence was committed by the youngest workers. Sometimes they stabbed other workers, sometimes they started fires, sometimes they punched foremen. Women workers were both targets of sexual violence and committed violent acts against male workers themselves. By 1973, there were 62 grievances that concerned violence at Dodge Main alone and 19 of them were acts of violence against management. And then in 1970, James Johnson, a black worker at another Chrysler plant, responded to racism and intimidation by murdering two white supervisors and a white coworker, an act celebrated by DRUM.

But it also took place the other way. In 1968, a white foreman threw a welding gun at a black worker. The worker than beat up the foremen. They were both suspended but the foreman showed up the next day anyway, leading to a brief walkout. When a gunshot paralyzed a Detroit housing activist, a Chrysler official told DRUM leader General Baker that the shot was meant for him. Moreover, the official said it was the UAW who organized the assassination attempt. Whether this was really true or not is unknown, but the UAW also flipped out over this. Milloy has the detailed records of grievance hearings and the personal daily notes of the head of the UAW in that plant. The union was both flummoxed and scared by the rise of violence. The head of the local basically thought blacks were violent people and could not act with any effectiveness in dealing with the problem, becoming more of an ally with Chrysler than to his own members. As with Lordstown, an aging leadership that came of age during the Great Depression and World War II simply didn’t know what to do. The Canadian UAW locals expressly compared themselves favorably to the U.S., but the same culture of violent masculinity still led to lots of problems there, including intimidation and sexual harassment of women.

Milloy makes larger points about workplace violence and its connection to the neoliberal society in which we live. He does so effectively. For me though, the bigger takeaway is how we remember and misremember work of the recent past. When we think about Walmart and McDonald’s, we often contrast them with GM and Chrysler. In a sense we should because of what a union contract means in terms of people’s lives. But there are more similarities than differences and we do not help ourselves by romanticizing what work used to be like. It was terrible and was basically always terrible. In thinking about the future of work, we can’t only focus on the financials. It’s also critical to fight for a workplace culture of decency, respect, and dignity. Too often, the UAW and other unions failed to do that. We can do better in the future. If we are ever to rebuild the American labor movement, we will need to do so .