People’s History of the Marvel Universe, Week 16: Days of Future Past and the Dystopian Dilemma

Days of Future Past is a good example of the peculiar (and volatile) alchemy that was the John Byrne /Chris Claremont partnership. According to Jason Powell, John Byrne was the driving force behind brining the Sentinels back as the primary and existential antagonists and the central time-travel hook was his unwitting homage to the Doctor Who serial “Day of the Daleks.”[2] However, as I’ll argue in this essay, a lot of the political and interpersonal story that the sci-fi stuff is wrapped around feels much more like Chris Claremont’s work, especially when it comes to the decision to center the story on Kitty Pryde.

This decision was key to making the broader transition from Dark Phoenix Saga to the rest of the Claremont run, because it comes only two issues after she’d joined the X-Men. Firstly, because her newcomer status perfectly positions her as the audience surrogate for the new, post-Jean Grey status quo, and secondly, because as the lone teenager on the All-New team, she makes for the better contrast with her no-nonsense veteran future self than anyone else. (This is somewhere where the 2014 film falls short, giving us a not-particularly-emphatic transition of Hugh Jackman going from one gradient of grizzled Wolverine to another.)

We can see the crucial clarity that Kitty provides in three panels, as she suddenly shifts from her initial fear of Nightcrawler’s appearance to her later warm and fuzzy feelings; similarly, the change from the uncertain, halting (“uh-huh”) speech patterns of Teenage Kitty to the matter-of-fact mission-briefing style of her adult self is immediately obvious.

How Is This Day Different All From Other Days

Another reason why Days of Future Past needs to be a Kitty Pryde is that (similarly to what he did with Magneto) Claremont made it into an inherently Jewish story. From the letters attached to clothing indicating which castes are allowed to “breed” in the Sentinels’ America, to the rows of identical graves near the gates of the “South Bronx Internment Center,” the visual and rhetorical signifiers of this particular post-apocalyptic scenario are uniformly that of the Holocaust:

In addition to the captions drawing meaning from Byrne’s discreet Hs and Ms on people’s jackets, we see Claremont’s sensibilities in Kate’s carefully-hidden thoughts – our first window into the Anti-Sentinel Resistance’s ideology. The similarity between Kate’s “we can try to ensure this nightmare never happens, never even begins” and the mantra of “never again” that became the definitive response to the Shoah is unmistakable.

We can also see Claremont’s influence in what he did with the time travel plot, allowing him to show how the X-Men’s characters could be wildly different in the far future of 2013. As I’ve talked about elsewhere, one of Chris Claremont’s enduring frustrations with the comics industry was the eternal status quo of serial IP:

But because the conceit of the story is that 33 years have passed, Claremont can show Colossus as a retired farmer (who can be married to Kitty Pryde without it being creepy) who’s given up the superhero life, can show us generational change with a grown-up Franklin Richards in an adult relationship with Rachel Summers (making her debut appearance) , and most of all can show us Magneto as Charles Xavier. Several issues before he was to do his major retcon on Erik Lensherr’s backstory, and fifty issues before he was to put Magneto on trial, Claremont shows us a Magneto who – transformed by pain – now fights to ensure that both “humanity” and “mutankind” can survive to see the “day after tomorrow.” (Incidentally, we know this to be Claremont’s contribution, because Byrne hated what he called “noble Magneto.”[3])

The ultimate example

of thumbing one’s nose at eternal status quo is permanent death of characters,

and one of the things that gave Days of Future Past its impact in 1981

is that the What If? nature of Byrne’s time-travel dystopia allowed for

the shocking deaths of X-Men mainstays like Wolverine and Storm without

damaging the X-book’s long-term brand:

At the same time, I think there’s more to these shocking deaths than the car-crash voyeuristic appeal of a “bad future” timeline, again due to Claremont’s spin on the story that we discussed above. The specificity of the apocalypse lends a specificity to the resistance fighting against it, and thus the Anti-Sentinel Resistance can’t help but take on some of the aspects of WWII resistance movements, which means also being influenced by the tropes of the cinema de résistance – films like Casablanca, Cross of Lorraine, This Land is Mine, Is Paris Burning?, and Army of Shadows. In this genre (influenced as it was by escape and heist films), the plucky Resistance fighters are generally outnumbered and outgunned, their best-laid plans are often undone by bad luck, and their ultimate victory is often the existential triumph of refusing to give in and collaborate.

The Terminator Scenario[4]

Now that we’ve fully explored the inspirations and implications of Byrne and Claremont’s dystopian future, we need to dig into the “present day” events that are supposed to set the apocalypse in motion and how Claremont wraps all of these events in an analysis of 1980s politics.

Breaking with the conventions of Marvel’s sliding timeline, X-Men #141 starts with a very specific date: Kitty Pryde walks into the Danger Room on “Friday, October 31st 1980…the final Friday in one of the closest, hardest-fought presidential elections in recent memory.” For once, Claremont’s purple prose is not exaggerating: in the real-world presidential election of 1980, October opinion polls stood on a knife-edge with Reagan and Carter trading leads, often divided by as few as three or four points, with third-party candidate still holding onto a potentially decisive 8-9% of the vote. This choice of date isn’t a coincidence, because as Kate Pryde will outline to the stunned X-Men, presidential politics will play a central role in creating this apocalypse:

First, the revelation that the dystopia will be caused by a presidential assassination immediately placed in the world of 1970s “paranoid” conspiracy thrillers like The Parallax View and Three Days of the Condor, themselves a reaction to the world-shaking political assassinations of the mid-to-late 60s as well as the more general increase in distrust in government that accompanied the Watergate scandal. And given how often these thrillers combined fears of assassination and conspiracy with fears of nuclear devastation – think Day of the Dolphin, The Odessa File, Twilight’s Last Gleaming, and The China Syndrome – here the link between the mutant metaphor and nuclear threat is particularly appropriate.

Second, for the first time we have a partisan political edge for the often-amorphous “anti-mutant hysteria.” Here, Claremont directly criticizes the (often hard-left) political terrorism of the 1970s, arguing that it backfires, creating a groundswell of fear and hatred that sweeps reactionaries into office. By trying to eliminate the threat posed by Senator Kelly in 1980, the Brotherhood of Evil Mutants only ensures that “a rabid anti-mutant candidate” is swept into office. This demagogue’s campaign slogan – “it’s 1984! Do you know what your children are?” – is a clever riff on the 1970s/1980s public service announcement campaign that sought to scare parents about the threat of juvenile delinquency with the question “It’s 10 PM. Do you know where your children are,” suggesting a parallel between moral panics.

Third, we see from these panels why the X-Men are such a crucial part of the Marvel Universe, and why arguments that they should be kept separate always fall flat for me. I’ve discussed elsewhere why the disparate treatment of mutants and other super-powered beings is actually a rich vein of storytelling ideas about model minorities vs. threatening Others, and why origin stories that emphasize random chance or super-tech produce very different social-psychological responses than those that emphasize powers acquired at birth. But here we see a new angle: Days of Future Past reminds us that as waves of hatred against one minority are allowed to grow ever higher, eventually the surge will swamp over conceptual boundaries to include all who are not in the in-group. Here, we see anti-mutant hatred expanding to encompass first outcasts and marginal types like Spider-Man, the Hulk (although how much more the Federal government could pursue the Hulk is unclear), and Ghost Rider (I’m genuinely quite puzzled how the government would even go about eliminating such a blatantly supernatural entity), but then to include “model minorities” like the Fantastic Four and the Avengers who are initially loved by the public and treated as auxiliaries of the state, and then finally national sovereigns like Doctor Doom of Latveria and Black Panther of Wakanda. (The cynical part of my mind suggests that it was only after the Sentinels went after these last two that the nuclear powers of Earth-811 stopped and took notice.)

Fourth and finally, given when these comics were written and published, we really can’t separate out the fear of a demagogue president who could start a crisis that ends with nuclear war from the fear of Ronald Reagan as someone whose aggressive policies towards the USSR might end in the missiles flying that existed in liberal circles that lasted up until the Reykjavik Summit in 1986. Hence why Days of Future Past is so concerned with the character of presidential candidates whether we’re talking about the or the unnamed firebrand from 1984 or Senator Robert Kelly.

Is Senator Kelly a Good Man?

Speaking of which, let’s talk about the character of Senator Robert Kelly.[5] In what might be something of a surprise for those of you who are primarily familiar with Senator Kelly from Bruce Davidson’s oleaginous performance in the 2000 film, much of the plot of Days of Future Past turns on the question as to whether or not Senator Kelly – clearly taking on the role of Ser Reginald Styles from “Day of the Daleks” – is a good person.

Throughout the two-issues, we get testimony to the affirmative: despite having every reason to hate the registration system that he inspired, Kate Pryde describes him as “a decent man” with “legitimate concerns about the increasing numbers of super-powered mutants;” Charles Xavier describes him as “scared” rather than bigoted; even the Blob, who’s literally there to assassinate him, calls Kelly “either the bravest man I ever seen or the dumbest.”

However, the broader context makes me question this informed attribute. After all, this isn’t the first time that X-Men readers have met the honorable gentlemen from the Acela Corridor – the first time we meet Senator Kelly is at the Hellfire Club, where he was a special guest of Sebastian Shaw. Given that Kelly was running for president at the time, it strikes me as very familiarly reckless to spend all of his time hanging out at an upscale sex club:

Kelly’s association with the Hellfire isn’t a one-off, but part of a longer pattern of behavior: not only does he return to the club in X-Men #246-7, but it turns out that Kelly’s wife Sharon is an ex-Hellfire Club waitress, which fact somehow completely escaped the national press corps during a presidential election and suggests a truly baffling campaign of Shaw’s to influence every aspect of his life. (And no, Kelly isn’t any more liberated about his wife being a former sex-worker than the IRL news media was about a certain Coloradan Senator’s open marriage.)

The Senator’s professional ethics are similarly questionable. Despite the fact that the ending of #142 establishes that Kelly serves on a committee with a national security portfolio, Kelly is the frequent guest of Sebastian Shaw, noted arms manufacturer with extensive contracts with the Pentagon. And while Kelly might not consider Shaw’s invites to be either an undeclared in-kind donation or some unauthorized lobbying, it’s pretty clear from the text that Sebastian Shaw absolutely does.[6]

Ethics aside, Kelly’s political ideology is way more troubling:

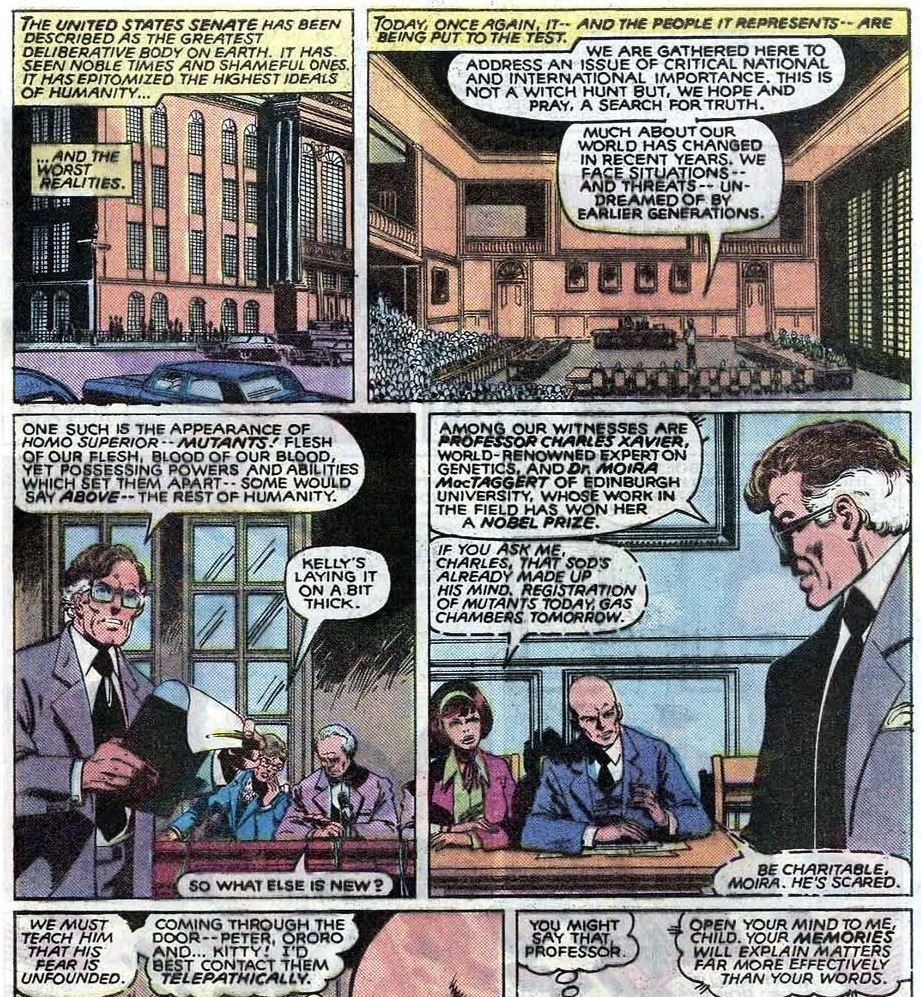

Kelly’s opening statement starts out as standard boilerplate establishment language – “we are gathered here to address an issue of critical national and international importance” – but then in the second panel veers straight into the insecurity-laden rhetoric of Bolivar Trask, which raises some questions about his objectivity. On a political side note, I’m utterly astonished that any campaign manager worth his salt would allow a presidential candidate to spend the last Friday before an election holding Congressional hearings, no matter how well-televised they may be.[7] No wonder Kelly doesn’t win the election.

At least the witness list hasn’t been stacked with partisans of Kelly’s position, because the ludicrously well-educated duo of Charles Xavier and Moira McTaggart are the main experts due to give testimony – which makes me curious as to which senators invited them. I particularly like this scene because it lets us see real political differences between members of the X-family: showing that he’s learned absolutely nothing from the last time he was kidnapped on live tv, Charles puts an inordinate faith in the power of reason and persuasion. By contrast, Moira channels both Claremont’s Holocaust-inspired opposition to state-sponsored classification and monitoring of minority groups and once of the most famous of (first openly gay elected official) Harvey Milk’s speeches.

Kelly gives the game away when he busts out his favorite Cro-Magnon/Neanderthal analogy, complete with an elaboration that situates his fear that there is no “place for ordinary men and women” in a world of superheroes – otherwise not that different from J. Jonah Jameson’s more targeted ressentiment – with a Madison Grant-esque fear of racial replacement, similarly founded on bad anthropology. Even his consistency that non-mutants like “Doctor Doom…the Fantastic Four [and] the Avengers” are also threats to the hegemony of baseline humans seems far less admirable, because we see the same list of names on the headstones at the South Bronx Mutant Internment Camp and in Kate’s description of the Sentinels’ future genocide.

Given the implications of Kelly’s beliefs, it becomes a little hard to buy his whole “just asking questions,” “this totally isn’t a witch hunt” schtick. I would argue eagle-eyed X-Men readers have good reason to question Kelly’s good faith, because this hearing is not the first time that Kelly has thought about “the mutant question.” As I mentioned above, Kelly just so happened to be hanging out at the Hellfire Club when the X-Men raided the place, and thus bought the party line:

Thus, well before any mutant hearings or attacks by radical mutant terrorists (more on this in a second), Kelly had already decided on the Sentinels as a solution to what he saw as the rampant criminality of “super-powered mutants” that conventional and Constitution-bound police forces “aren’t equipped to fight.” Note that the nameless NYPD captain’s mention of the Fantastic Four and the Avengers in this context suggests that Kelly’s inclusion of them in his testimony is perhaps due to the fact that these groups are neither “completely” nor “unquestionably under Federal government control.”

In the context of the dystopian scenario posited by Byrne and Claremont, it turns out that the supposed moderate option was the same agenda as that of the demagogue, just dressed up in fancier language. (This is not the first or last time that no-win scenarios will show up in Days of Future Past.)

So why don’t we see “Moira Was Right” T-shirts in the X-fandom?

The Revolutionary Mystique

But enough like the victim, let’s talk about the assassin, Mystique. Her inclusion in this story – indeed, Days of Future Past is Raven Darkholme’s first appearance as an X-villain – is clearly Claremont’s influence. Despite being a mutant from the jump, Mystique was originally a Ms. Marvel villain co-created by Claremont and Dave Cockrum. Mystique is a perfect fit for the paranoid thriller style, both because her mutant abilities mean that she could be anyone and anywhere, and because she’s already infiltrated the highest reaches of the military-industrial complex:

One of the confusing elements of Days of Future Past is that Mystique recreates the Brotherhood of Evil Mutants, complete with its initial peculiar name, despite not having any connection to Magneto or any discussion of what her inspiration for the group’s name was. It feels as if Claremont missed a trick here by not having Mystique’s group be the first Mutant Liberation Front, which would be more evocative of similar groups from the 1970s, create some distinction between this and the first Brotherhood (which it has no overlap with). On the other hand, the fact that she kept the original name, and the self-marginalizing perspective it implies, does suggest that Mystique may be more of a fan of Magneto’s early work than his more sophisticated later years.

This becomes especially clear when Mystique and the Brotherhood arrive at the Capitol: in a scene that demonstrates that, often, hardliners on opposite sides are de facto allies because their mutual provocations lead to complementary radicalization, Mystique and the Brotherhood are in total agreement with Kelly’s eugenic philosophy, just with a different emphasis. Because they see themselves as the “first Cro-Magnon” to his “last Neanderthal,” they see it as less an existential threat as a prophecy of historical dialectic[8]:

Costumes and super-powers aside, Mystique’s approach here isn’t that different from the Red Brigades of the 1970s, whose kidnappings (and occasional assassinations) of political figures were carried out with a keen eye towards mass media through the granting of interviews with journalists and the issuing of manifestos and other communiques to be published in the world press. Here, Mystique’s plan is quite simple:

Unusually for the Claremont era, the climax of Days of Future Past is a straight-up superhero fight between a team of “good mutants” and a team of “bad mutants,” with the X-Men in the position of having to once again fight for “a world that hates and fears them,” which is much more of a Silver Age paradigm. Where we see more of a Claremontian influence is around the margins of the wrasslin:

To begin with, we see Claremont’s fascination with fully-lived-in minor characters and the power of the news-media in the fact that he drops in a reporter to react to the burgeoning story.[9] In addition, the broader themes of post-Watergate political paranoia continues in the fact that the first reaction of bystanders to the bombing of the U.S Capitol – which was bombed by the Weather Underground in 1971 – is a false-flag operation by the White House.

But the biggest influence

of all is that while Wolverine and Colossus team up to see-saw the Blob into Avalanche,

Nightcrawler has a doppleganger

fight with his mother, and Storm rains on Pyro’s parade, it’s Kitty Pryde

who actually saves the day:

It wouldn’t be a Claremont issue if the climactic showdown of Days of Future

Past wasn’t 90% political debate about whether political terrorism is

ultimately self-defeating and only 10% action. (Another sign that this part of

the story was Claremont’s rather than Byrne’s is that the latter hated what he

called the “semi-incestuous lesbian kiss.”[10])

The Dystopian Trap

Unfortunately for Kate Pryde, it turns out that however personally brave (and/or bloodthirsty) he might be, it turns out Senator Kelly is both a committed ideologue (as we discussed above) and wildly ungrateful for her saving his life:

While I’ll get to the broader implications in a second, I did want to note some important elements of the content of this epilogue:

- Firstly, Senator Kelly’s politics remain as baffling as ever: one month after an election he presumably lost despite the rallying effect you’d think would come from surviving an assassination attempt related to your number one issue four days before the election, Senator Kelly is working hand-in-glove with someone who would have been his presumable rival.[11]

- Secondly, President Silhouette’s politics aren’t much better: despite arguing that Kelly’s proposal is “dangerous…unconstitutional, even criminal,” the President nevertheless decides to continue the same approach as a “covert” initiative outside of Congressional and judicial oversight, which seems substantially more unconstitutional and criminal than Kelly’s proposal, which presumably called for some form of authorizing legislation. (This is a topic I’ll get into in more detail when the People’s History of the Marvel Universe covers the various Registration Acts…)

- Thirdly, we are introduced to Henry Peter Gyrich, future antagonist to both the X-Men and the Avengers. I find Gyrich endlessly fascinating, because I can’t think of that many real-life figures who spawned not one, but two, stand-ins. It’s almost like H.R Haldeman did something to really inspire antipathy in people of a certain generation.

- Finally, it’s important to note that the main reason why Kate’s intervention “didn’t work” (more on this in a second) is because the Anti-Sentinel Resistance was so focused on the role of the Brotherhood and Senator Kelly that they didn’t see the more insidious threat of the quisling Hellfire Club.

So let’s talk about the Twilight Zone-style stinger ending – that, contrary to the previous page’s narration that Kate’s actions collapsed the Earth-811 timeline, and thus “reality twists inside out,” Kate’s intervention and the 2013 X-Men’s sacrifices have not halted the threat of the Sentinels. It is unarguable that the impact of this ending was a major reason why Days of Future Past was such an enduring success.

And that’s the problem: over the last almost-forty years, X-creators and fans alike have been so profoundly influenced by this story that we’ve become incapable of imagining a future for the X-Men that isn’t a dystopia. Part of this has to do with comics’ unfortunate tendency to repetition: since the original, we’ve had Days of Future Present, Days of Future Yet to Come, Wolverine: Days of Future Past, and Secret Wars: Years of Future Past, all of which explicitly continue, elaborate on, or reboot the Earth-811 continuity. (I would also argue that Age of Apocalypse and its successors are profoundly influenced by DOFP as well, since they also involve time travel, assassinations, dystopian futures, Sentinels, and nuclear threat.)

I would argue that this kind of enforced nihilism is creatively deadening in any case, but it becomes especially problematic for a comic book which doubles as a metaphor about oppressed minorities. The implicit argument is that there is no hope for the future, no possibility of either eliminating dismantling either cultural bigotry or systematic discrimination, no potential for progress either in reformist or revolutionary fashion, and given how often these dystopias involve worlds in which mutant hegemony is the oppressive force, that trying to change things only makes them worse.

If D.C can give us

the Legion of Super-Heroes or the New Gods, it is not beyond the capacity of

Marvel to imagine a future that doesn’t fall into the dystopic trap. While I

understand that as action-oriented dramas, the superhero genre requires

conflict, but there is a middle ground between utopia and dystopia. Here, the protean

nature of the metaphor can be our guide: when in the history of the world

has the success of a social movement or the liberation of a people from oppression

not seen backlash, the rise of new issues, or the formation of new group identities?

[1] Yes, I know I said during an earlier PHOMU that the Hellfire Club was his first statement on the mutant metaphor, but to be fair the Hellfire Club was introduced as part of a story that’s really more about space opera and cosmic weirdness, so I feel Days of Future Past qualifies as the first story that is about the metaphor above all else.

[2] Jason Powell, Best There Is At What He Does, loc. 1242.

[3] Powell, loc. 1272.

[4] While I didn’t want to let it overshadow the overall argument of the essay, I can’t let it pass without note that Days of Future Past eerily predicts many of the core plot elements of Terminator – genocidal robots, time-travel, apocalyptic scenarios, nuclear war, and so on – although unlike the celebrated legal case between Harlan Ellison and James Cameron, this is likely a case of parallel evolution.

[5] It’s really unclear in the main X-Men continuity what Senator Kelly’s party affiliation and state are. Only in X-Men: Noir is he described as a Republican, but the political context of 2009-2010 was very different from that of 1980-1981 and there’s really no signs of that in the original text. As for what state he represents, all I can say is that he seems to spend an awful lot of time in New York City (which is fairly standard for the Marvel Universe), which suggests he’s a Senator from somewhere on the Eastern Seaboard.

[6] As a public service to my readers, I reached out to my friend and colleague Dante Atkins to ask him whether Kelly’s relationship with Shaw would violate Senate ethics rules. On the face of it, having Shaw guest Kelly at his incredibly exclusive club would generally be considered a gift worth more than $50, which could trigger all kinds of problems (not just with Senate Ethics, but potentially the FEC and the Public Integrity Section of the Department of Justice) if Kelly didn’t declare it on his forms, especially since Shaw definitely lobbies him on Project Wideawake. (More on that later.) Unfortunately, the fact that Shaw and Kelly are longstanding friends probably means that this would fall under the “personal friendship exemption,” unless someone could “prove that Shaw is offering this to Kelly not out of personal friendship, but because he is a sitting Senator, and would not do so if he weren’t.” Just goes to show that whether in Earth-616 or our world, Congressional ethics rules are in dire need of reform.

[7] By contrast, John McCain suspending his campaign in late September 2008 was way more reasonable, both in terms of distance from the election and the importance of the issue.

[8] One of the ironies of Mystique’s radical positioning in Days of Future Past is that she’s going to spend far, far more of her career as an agent both willing and unwilling of the human state than she ever did as a mutant revolutionary.

[9] Granted in this case, the reporter is a fictional one from Doonesbury, but you get the sense that this scene was something of an inspiration for his inclusion of the very real journalists Neal Conan and Manoli Wetherell of NPR in Fall of the Mutants.

[10] Powell, loc 1311.

[11] It is possible that President Silhouette is termed out and thus a political ally of Kelly’s, but that seems somewhat unlikely since Project Wideawake is clearly a personal initiative of his, and the clandestine scheme continues into the next administration (i.e, for at least 40 more issues).

I’d like to thank my Patrons: Beth Becker, Anonymous, Steven Xue, Gabriel Nichols, Casso King of Seals, Stephan Priddy, Sister Winter, Alistair, Aweseeds, Quinn Albaugh, James Tuttle, Hedrigal, Jeremy Alexander, Clint Woods, Dan Kohn, Donald Newell, joannalannister, Abel Savard, Quinn Radich, Emmett Booth, Leonard Wise, Kelly, Andrea Krehbiel, Courtney Simpson, Will Pepperman, Angus Niven, Lauren Combs, Amanda Marie Ford, Danil Koryabkin, John Pharo, Darby Veeck, History of Westeros, Joshua Imboden, Imriel, Adam Blackwood, Greg Sanders, Alex Chiang, William Griese, NotAPodcast, Chris Reid, tomsevenstrings, Timothy Upton, Patrick Donohoe, Willie Frolik, Micah Bouchard, Lucas Fyten, Gabriel Mallows, Paul Connolly, Brett, Michael Aaronson, Nina Friel, Christine Higgins, Jason Reilly Arends, Jim Tripp, Eric Benjamin, Sara Michener, Dave, James Keene, and Martina Consalvi.

If you’d like to become a Patron and support Race for the Iron Throne, see here.