Herodotus

The Podcast

A couple of months ago I recorded a War Room podcast with Dr. Jacqueline Whitt of the Army War College. We discussed why the Army War College, and its sister institutions, have so heavily focused on Thucydides instead of other ancient historians and theorists. For me, the triggers for thinking about this had been a decision to listen to History of the Peloponnesian War on Audible, followed shortly thereafter by my appointment to the USAWC, which involved three class days of discussion of Thucydides’ text. I was so happy with the intellectual experience of listening to Thucydides that I followed it up with Herodotus, Xenophon’s Anabasis, the Annals and the Histories of Publius Cornelius Tacitus, and Commentaries on the Gallic War by Julius Caesar. In the podcast we discuss Herodotus and Xenophon, mostly because they so closely booked Thucydides but also because I hadn’t yet finished Caesar (the subject matter of Tacitus is sufficiently removed from the mission of the War College that I don’t think it fits well with the others).

The Project

My project here is to think through how an institution like the War College might use Herodotus, Xenophon, and Caesar more effectively; for example, is three days of Thucydides appropriate, or would it be better to do a day of Herodotus followed by a day of Thucydides followed by a day of Xenophon? I think Polybius might also be a good candidate, but it’s been a while since I read him. I approach this question as a security specialist, rather than as a classicist. The debates over the history, meaning, and context of these sources are obviously relevant and should inform their use as didactic tools, but the question of their utility within a syllabus depends on course goals.

In this, I’ve also been fortunate to be able to sit in on an elective run by Dr. John Bonin and Major Mark Balboni on Warfare in the Ancient World. This elective digs into Herodotus, Xenophon, Caesar and other in considerably more detail than the regular War College courses, and has informed some of the thinking in this series.

First up, naturally, is Herodotus. Herodotus was regarded as the most relevant of the Greek historians for much of the pre-modern and early modern period. The dominance of Thucydides is a relatively recent phenomenon. Reading the two side-by-side, it’s not difficult to see why; Herodotus’ story is an entertaining story about a series of massive events, told with plenty of fascinating sidebars about the people of Western Asia and North Africa.

The Problems

The first problem is with method. Thucydides has a method, tells you what it is, and seems, mostly, to want to hold to it. This makes it easier for both students and faculty to digest (“this probably really happened more or less like this”). Herodotus, on the other hand…

That’s not completely fair; “I heard several stories and one of them may be true” is a *kind* of method, but not one that’s easily intelligible to the modern manner of thinking about evidence and causality. Faculty members want their students to take them seriously, and when Herodotus starts ruminating about why all Ethiopians live beyond 120 years old, it becomes a struggle to maintain the attention of the literal-minded. Herodotus has a cultural and anthropological eye, and some of what he writes about the various nations of the ancient world is possibly mostly true. It’s difficult to sort out which, however, and the strategic studies audience is not particularly moved by Herodotus’ literary value.

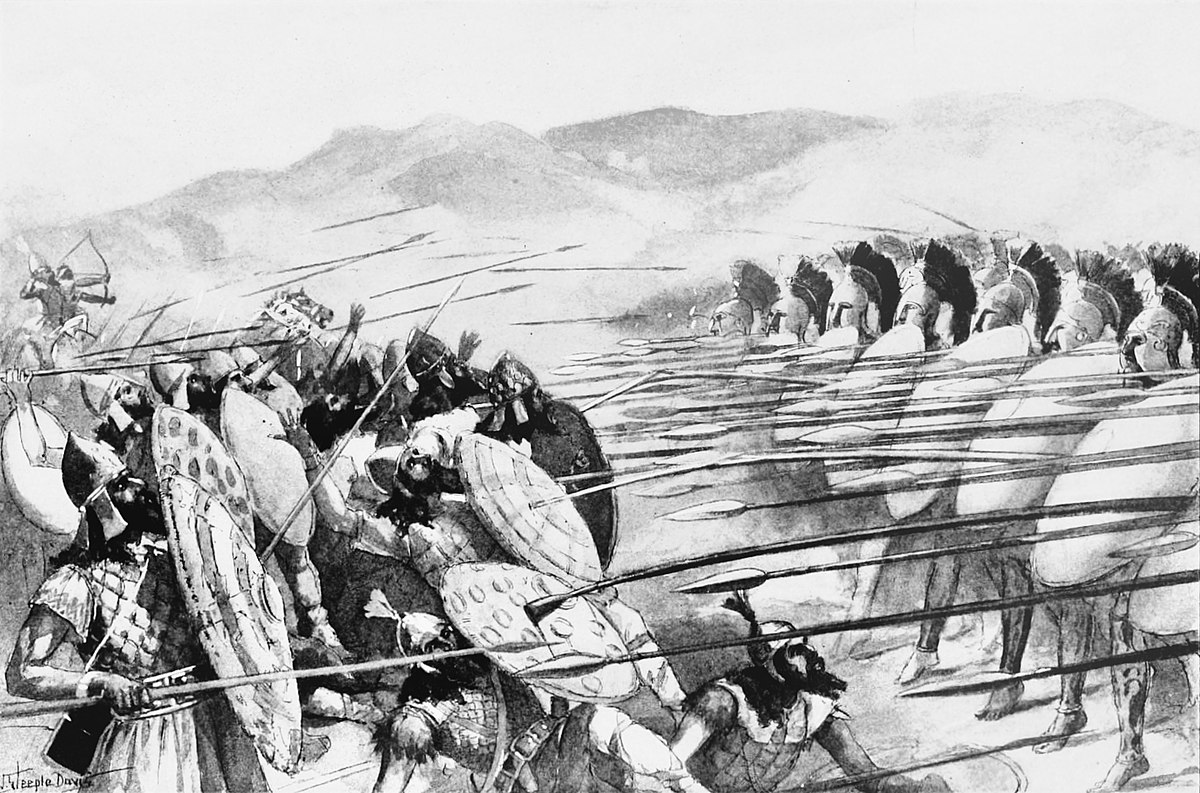

The second problem is that while the central subject of his story is the rise of the Persian Empire and the invasions of 490 and 480, Herodotus is not all that interested in telling a history of war, and not all that good at depicting battles. It’s remarkable that the Battle of Thermopylae has become a cultural touchstone in the West, because Herodotus really tells us very little about what happened there, and when he does try to describe the situation it’s often quite flat. All of the Spartans died, of course, but Herodotus had both Greek and Persian sources to draw upon for a more vivid account of the battle. Unlike Thucydides (or Xenophon), Herodotus doesn’t offer us very much of interest about how battles were fought. He lacks a soldier’s eye and ear for what’s important on the battlefield. Even where he has good sources, as with Plataea or Marathon, we have to reconstruct the situation based on a contrast between what Herodotus tells us and what makes logical sense. While there’s certainly a kind of upside to this (Hans Delbruck’s reconstruction of Marathon is a classic), a little goes a long way.

The Opportunities

Not all of Herodotus’ battle accounts are bad; his description of the prelude to the Battle of Plataea is quite strong, although he doesn’t manage to follow up by offering a compelling description of the battle itself. His discussion of Greek and Persian preparations is strong, and his account of the argument between Spartan commanders during a retrenchment (one Spartan commander didn’t get the memo and refused to “retreat,” leading to an hours-long argument in the middle of the night about whether it was a retrenchment or retreat, the throwing of rocks, etc.) is just flat-out hilarious to read. He clearly had enough sources to give a good account of how the Athenians and Spartans were thinking about the battle, which is helpful for purposes of thinking about alliance contributions in warfare.

Herodotus also offers a window into operational thinking in a way that few ancient authors can match. Operational thinking, for those unfamiliar, is the idea of planning for a sequence of connected, mutually supporting maneuvers that produce the opportunity to fight a decisive battle. Most modern military thinking argues that the operational level of war, as opposed to the tactical (lower) and the strategic (higher) is a product of the nineteenth century, where modern communications and logistics allowed commanders to think in terms of disparate-but-mutually-supporting forces.

That conclusion is up for dispute, but it’s fair to say that neither Thucydides nor Xenophon offer a window onto operational-level planning. In the former, generals often show up in an area with an army and a vague sense of what’s possible, but don’t have careful plans that require close coordination between multiple formations and logistical centers. Brasidas in Thrace and Demosthenes at Pylos, for example, are often catch as catch can rather than tightly planned campaigns. Even the planning for the Sicilian Expedition is frustratingly vague in terms of what the army and navy were supposed to do when they arrived at the island; halfway there, the main generals were still arguing about the goals and execution of the campaign. For his part, Xenophon just wants to get OUT, and for the most part his efforts to set up any kind of coordination with external forces fail.

Given that, it’s surprising that Herodotus paints a picture of operational-level thinking on both the Persian and Greek sides. The Persians invade Greece with two mutually supporting forces, one at land and one at sea. They understand that the success of one enables and requires the success of the other, and take elaborate steps to maintain coordination. The Greeks understand the Persian plan and develop complex, sequential efforts to disrupt that coordination. Thermopylae is an example of one of these, and once the Persian victory becomes evident it triggers a sequence of changes in Greek planning (impressive because of the difficulties of coalition warfare). In stark contrast to the stories told by Thucydides and Xenophon (and, later, Caesar) these campaigns feel almost modern in the kind of planning that they would require. Of course, Herodotus may simply be imposing order and interpretation where he has no business doing so, and the actual process may have been more chaotic than he allows, but it’s still a different vision of ancient campaigning.

Finally, Herodotus provides useful context for engaging with Thucydides, and not just insofar as he sets the stage. To my mind, Thucydides quite clearly loathed his older colleague, and there are numerous points in History of the Peloponnesian War that essentially amount to nasty subtweets of Herodotus. Appreciating Herodotus helps us to appreciate Thucydides, both in terms of his methodological innovations, and in that the former allows us to be skeptical of the latter; it’s very difficult to take seriously Thucydides claim that the Peloponnesian War is the great conflict in human history in light of the much larger, much more consequential Persian War.

Wrap

On balance… I can see why we exclude Herodotus, given the methodological issues. Herodotus is interested in war as a Great Historical Event, but he’s not interested in war as a political or social phenomenon in the same way as Thucydides and Xenophon. It’s hard to argue that he should be used at the expense of T-Diddy. But for excerpts, the prelude to the Battle of Plataea is worth our valuable time. If there’s a bit more time to spare, Books VII, VIII and IX tend to remain on point with respect to the planning and execution of the second invasion of Greece.