Sunday Book Review: Arnhem, Ten Days in the Cauldron

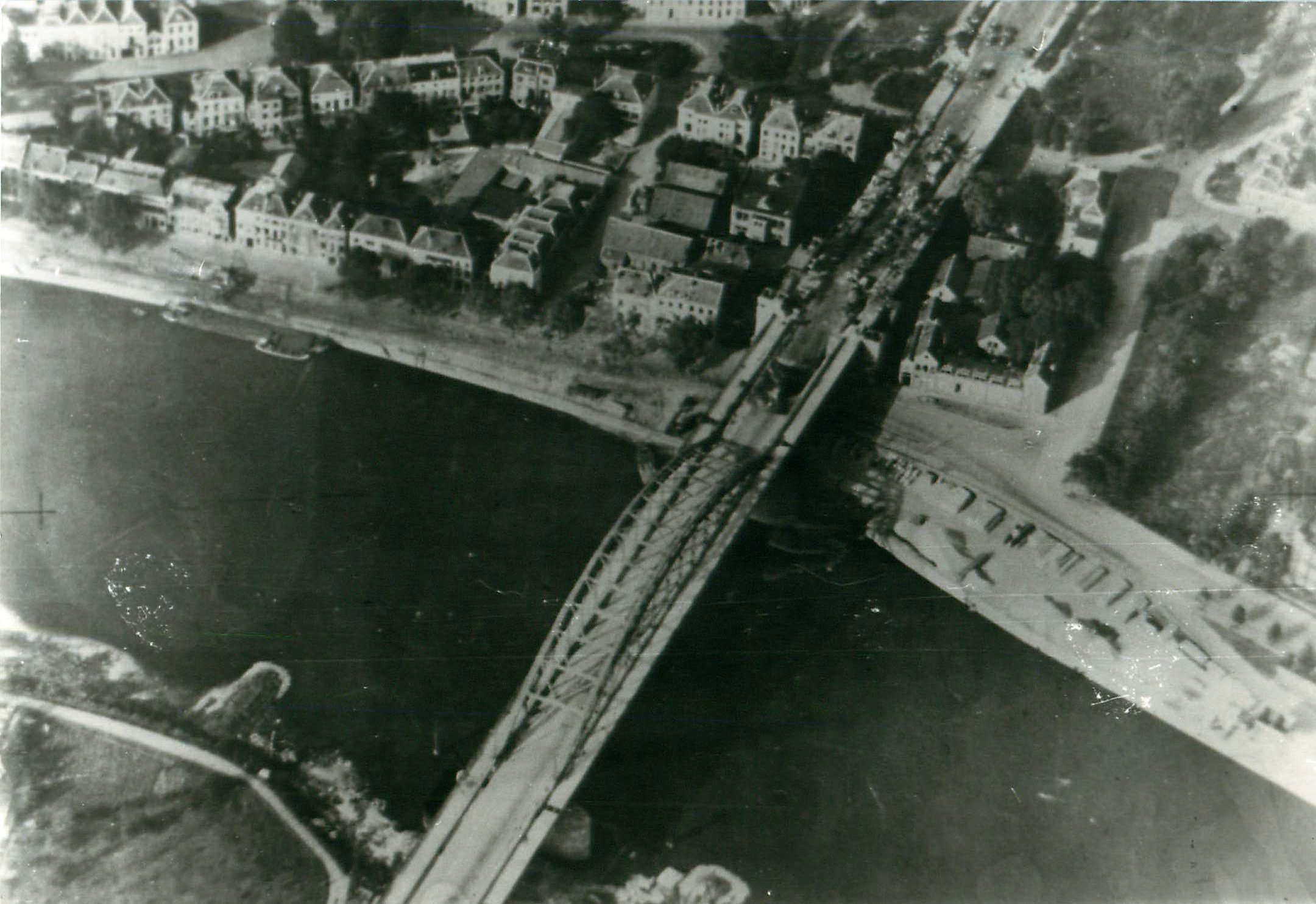

Iain Ballantyne’s Arnhem: Ten Days in the Cauldron is a tapestry of the human stories behind the failed Allied attempt to seize the bridge at Arnhem. Operation Market Garden was intended to seize a series of bridges that would give the Allies a pathway across the Rhine, access to the Ruhr, and a chance to bring about the collapse of the Third Reich in 1944. It didn’t work out. Ballantyne (who, full disclosure, is a friend and has edited my work at Warships: International Fleet Review) offers an individual level perspective on the battle, which compliments the other works already available on the course of the battle.

As with his work on the sinking of the Bismarck and his submarine books, in Arnhem Ballantyne is most interested on the individual dimension of war. At time this can be difficult for the reader, especially for those of us who don’t have tight familiarity with the battle; there are few maps, and little in terms of directions regarding where the major formations were and how they were moving. For my part, Arnhem is one of the battles of World War II that I am least familiar with. But the operational and strategic level details are easy to find on Wikipedia. Instead, Ballantyne gives us accounts from individual British and German soldiers, as well as from Dutch civilians.

The book begins with an account of the glider landings on D-Day, which foreshadow the similar efforts In Market Garden. British landings were somewhat more scattered than had been hoped for, but the big problem was the toughness of German resistance. The Germans fought with a tenacity that the British did not expect, especially as the operation was premised on the idea that German forces were weakened, demoralized, and nearly in full flight. Initial success in holding the British and Poles bred more success, as German morale improved and fighting attitudes hardened. That the British kept dropping supplies on the German undoubtedly improved Wehrmacht attitudes.

Fighting in and around Arnhem was brutal, often descending into short range and hand-to-hand combat. German tanks blasted through the hiding places of the British, just as British soldiers found creative ways to kill tanks. British command and control was a struggle, even as the local telephone system somehow miraculously remained intact. The commander of the 1st Airborne Division, Major General Roy Urquhart, at one point had to kill a German with his sidearm. As the prospects for success dimmed, British resistance grew more desperate, until the commencement of a general withdrawal. Towards the end, a few British soldiers simply don’t receive the order to withdraw, and are left with dozens of German prisoners.

The experience was obviously also quite brutal for the Dutch, who saw their town destroyed around them. Ballantyne relies on a pair of Dutch accounts, including most importantly the story of a family who harbored a group of British soldiers in their cellar before the house was completely destroyed by German fire. But amid the brutality there were signs of civilization; both the Germans and the British attempted to limit the extent of damage to civilians, and both sides made efforts to handle wounded and prisoners in a humane way. Many of the individual accounts Ballantyne discusses come from soldiers who became prisoners of war, some of whom escaped before the end of the conflict.

Of course, the Germans prevailed in battle, squeezing the British out while capturing or destroying any remnants. That outcome, however, is strangely unimportant to the story Ballantyne tells, which is about how soldiers who had fought each other under brutal conditions for some five years managed to pull together the energy to fight each other again. It is a fine book, definitely worthy of the attention of anyone interested in the thinking and motivation of soldiers fighting in the last battles of World War II.