David Souter’s alternate path on poltical corruption

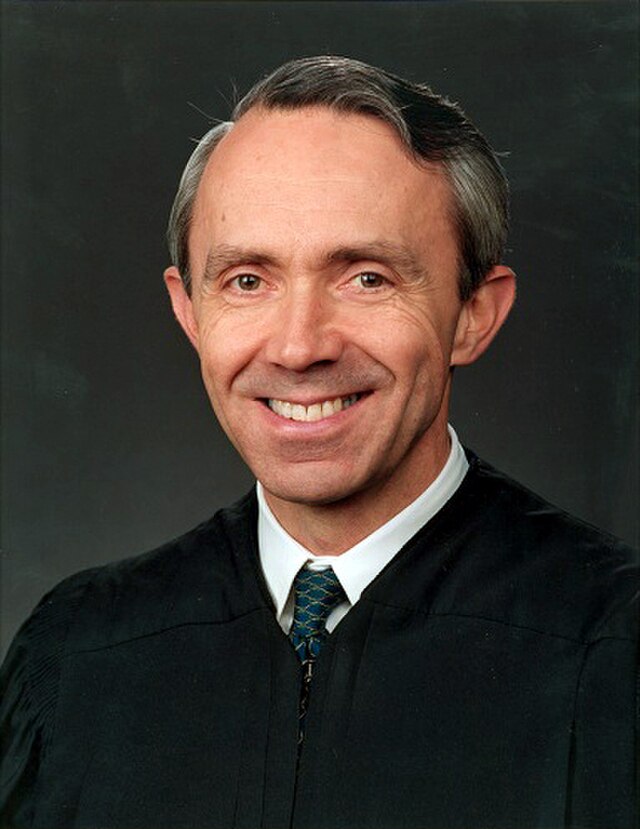

The late David Souter was perhaps the Court’s strongest voice on behalf of the ability of legislatures to put reasonable restrictions on political donations and spending. Rick Hasen has a story about how Sandra Day O’Connor forced him to remove a critical justification for campaign finance reform from his opinion in Shrink Missouri as a price for keeping her vote:

At issue in Shrink Missouri was whether Missouri’s campaign contribution limits were set unconstitutionally low, making it impossible for some candidates to raise money for their campaigns. In a 6–3 opinion written by Souter, the court upheld the limits as justified on anticorruption grounds and not a violation of the First Amendment. (It’s a decision that today’s much more antiregulatory Supreme Court has since effectively overruled.)

An early draft of Souter’s majority opinion in Shrink Missouri sought to expand the definition of corruption to include concepts of political equality. After quoting Buckley about the dangers of “improper influence” and “opportunities for abuse” that justified some campaign finance limits, Souter’s Shrink Missouri draft explained that in Buckley the court “made clear that we recognized a concern not confined to bribery of public officials, but extending to the broader threat that politicians grown dependent on large contributions will lose critical independence and instinctively identify interests of a plutocracy with the public good.”

Unfortunately, Souter’s warning of an emerging plutocracy never made it into the final version of Shrink Missouri. O’Connor complained about the line, calling it an “unnecessarily sweeping definition of ‘corruption’ … one which goes beyond Buckley’s concern with quid pro quo corruption and the appearance thereof.” Souter agreed to remove the line, remarking to O’Connor: “You drive a hard bargain.” The new language more meekly described the broader threat of big money as “politicians too compliant with the wishes of large contributors.”

The omission was unfortunate because Souter’s original insight was profound and surely right. When politicians spend all their time around the super wealthy and depend upon their support, they will increasingly identify with their interests and values. And this is as true of Justice Clarence Thomas and his benefactor Harlan Crow as it is all of the presidential candidates who now depend upon megadonors to fund super PACs to support their campaigns.

When Souter wrote his opinion in 2000, we did not have—as we do today—donors giving tens of millions (and in two cases, more than $100 million) to outside groups that can work hand in hand with candidates so long as they have good lawyers to avoid legal pitfalls. It is no surprise that, as Marty Gilens and Benjamin Page have found, the interests of the super wealthy are much more likely to be reflected in public policy than the interests of the average American.

The idea that Souter’s view is inconsistent with “free speech” is true only if you ignore the legal regimes of most liberal democracies. And the Court’s extremely narrow definition of “corruption” and rejection of the importance of poltical equality continues to be reflected in multiple doctrinal lines, to the detriment of the country. R.I.P.