Progress and its discontents

From commenter Karen, aka Cassandra of Texas:

Because I need to be optimistic at the moment, I’m going to suggest that one reason things look so bad now is that we are only now paying real attention and trying to fix things. Have y’all ever cleaned a cabinet or room or entire house that had been neglected for a long time? There’s a stage in the middle of the process where all the junk is out on the floor and all the dust and dead bugs and mold is visible to the world. It looks MUCH worse than things did before you started. There is a temptation at that point to just stop and pile all the junk in slightly neater stacks back and quit the whole job. That would be wrong. The only way out is through. So, you keep going, seeing what can be cleaned or mended and what has to be thrown out. There will be several days where the stuff to be thrown out is bagged up but still in the way because you haven’t taken it to Goodwill or the truck hasn’t arrived to haul it off. In the worst cases, there are structural repairs that have to be done, keeping the mess around longer. It is tempting to think that abandoning the whole place to rats and raccoons and spiders is the correct course of action, but it really never is. So, again, the only way out is through.

We’re in that ‘all the junk is now in the middle of the floor and I can see the water stains, mold, and roach nests’ phase of racism and sexism. It’s worse because there are still people who can’t see the problem and other people who think living with rats and cockroaches and cobwebs is the ideal human state. The simple fact that we’ve started cleaning is, however, a real achievement. The project is bigger than each of us as individual but very much feasible with all of us working together. So, get your cleaning gloves, put on your schmattes, and grab a garbage bag, some paper towels, and a broom and let’s finish this job.

This I think is very wise, and all the more so as I am the kind of person who, when seeing a domestic catastrophe of the sort Karen describes, falls instantly into a sort of Iberian Catholic fatalistic paralysis. My wife, of Swedish Protestant heritage, has exactly the opposite reaction (I realize these ethnographic generalizations are rather broad).

In Anna Karenina, the sight of his dissolute dying brother paralyzes Levin with sorrow and despair. But his wife is moved to action:

Levin could not look calmly at his brother; he could not himself be natural and calm in his presence. When he went in to the sick man, his eyes and his attention were unconsciously dimmed, and he did not see and did not distinguish the details of his brother’s position. He smelt the awful odor, saw the dirt, disorder, and miserable condition, and heard the groans, and felt that nothing could be done to help. It never entered his head to analyze the details of the sick man’s situation, to consider how that body was lying under the quilt, how those emaciated legs and thighs and spine were lying huddled up, and whether they could not be made more comfortable, whether anything could not be done to make things, if not better, at least less bad. It made his blood run cold when he began to think of all these details. He was absolutely convinced that nothing could be done to prolong his brother’s life or to relieve his suffering. But a sense of his regarding all aid as out of the question was felt by the sick man, and exasperated him. And this made it still more painful for Levin. To be in the sick-room was agony to him, not to be there still worse. And he was continually, on various pretexts, going out of the room, and coming in again, because he was unable to remain alone.

But Kitty thought, and felt, and acted quite differently. On seeing the sick man, she pitied him. And pity in her womanly heart did not arouse at all that feeling of horror and loathing that it aroused in her husband, but a desire to act, to find out all the details of his state, and to remedy them. And since she had not the slightest doubt that it was her duty to help him, she had no doubt either that it was possible, and immediately set to work. The very details, the mere thought of which reduced her husband to terror, immediately engaged her attention. She sent for the doctor, sent to the chemist’s, set the maid who had come with her and Marya Nikolaevna to sweep and dust and scrub; she herself washed up something, washed out something else, laid something under the quilt. Something was by her directions brought into the sick-room, something else was carried out. She herself went several times to her room, regardless of the men she met in the corridor, got out and brought in sheets, pillow cases, towels, and shirts.

And, after all, despite the profound horrors of the present moment, great progress has been made over the past few decades, which is precisely why the reactionary backlash to that progress is so intense. I’m old enough to remember the racial and gender politics of the 1970s, and the slow painful advance toward that most feared and hated of things, a world of free and equal human beings, has been very real. And this doesn’t even take into account that even a half century ago, racial and gender progress had already been tremendous compared to a half century earlier (We will for the purposes of this optimistic message pass over in silence class dynamics for the moment). Consider, for example, how many previously unmarked categories have been made visible in the intervening years, and how much more difficult it is to ignore the existence of “the others.” (Again, it is these dynamics that inevitably provoke backlash.)

Orwell:

WHO wrote this?

***

As we walked over the Drury Lane gratings of the cellars a most foul stench came up, and one in particular that I remember to this day. A man half dressed pushed open a broken window beneath us, just as we passed by, and there issued such a blast of corruption, made up of gases bred by filth, air breathed and re-breathed a hundred times, charged with the odours of unnamable personal uncleanliness and disease, that I staggered to the gutter with a qualm which I could scarcely conquer. . . I did not know, until I came in actual contact with them, how far away the classes which lie at the bottom of great cities are from those above them; how completely they are inaccessible to motives which act upon ordinary human beings, and how deeply they are sunk beyond ray of sun or stars, immersed in the selfishness naturally begotten of their incessant struggle for existence and incessant warfare with society. It was an awful thought to me, ever present on those Sundays, and haunting me at other times; that men, women and children were living in brutish degradation, and that as they died others would take their place. Our civilization seemed nothing but a thin film or crust lying over a bottomless pit and I often wondered whether some day the pit would not break up through it and destroy us all.

***

You would know, at any rate, that this comes from some nineteenth-century writer. Actually it is from a novel, Mark Rutherford’s Deliverance. (Mark Rutherford, whose real name was Hale White, wrote this book as a pseudo-autobiography.) Apart from the prose, you could recognize this as coming from the nineteenth century because of that description of the unendurable filth of the slums. The London slums of that day were like that, and all honest writers so described them. But even more characteristic is that notion of a whole block of the population being so degraded as to be beyond contact and beyond redemption.

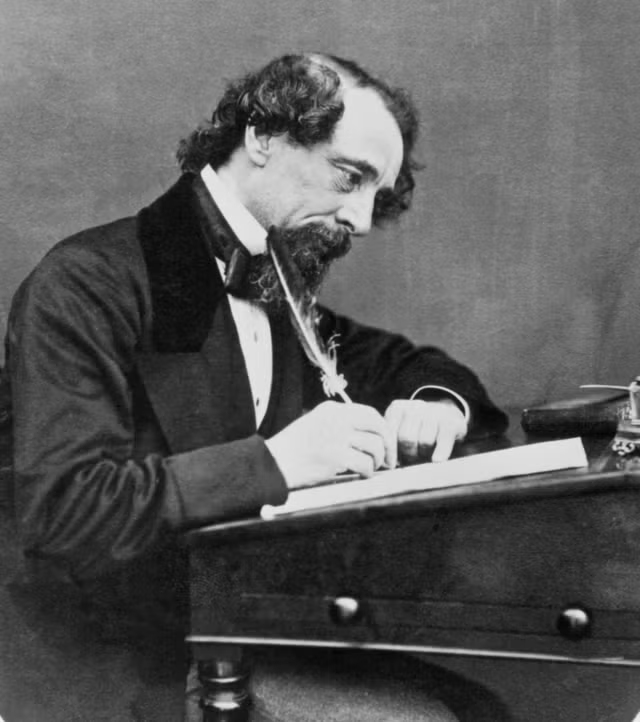

Almost all nineteenth-century English writers are agreed upon this, even Dickens. A large part of the town working class, ruined by industrialism, are simply savages. Revolution is not a thing to be hoped for: it simply means the swamping of civilization by the sub-human. In this novel (it is one of the best novels in English) Mark Rutherford describes the opening of a sort of mission or settlement near Drury Lane. Its object was ‘gradually to attract Drury Lane to come and be saved’. Needless to say this was a failure. Drury Lane not only did not want to be saved in the religious sense, it didn’t even want to be civilized. All that Mark Rutherford and his friend succeeded in doing, all that one could do, indeed, at that time, was to provide a sort of refuge for the few people of the neighbourhood who did not belong to their surroundings. The general masses were outside the pale.

Mark Rutherford was writing of the seventies, and in a footnote dated 1884 he remarks that ‘socialism, nationalization of the land and other projects’ have now made their appearance, and may perhaps give a gleam of hope. Nevertheless, he assumes that the condition of the working class will grow worse and not better as time goes on. It was natural to believe this (even Marx seems to have believed it), because it was hard at that time to foresee the enormous increase in the productivity of labour. Actually, such an improvement in the standard of living has taken place as Mark Rutherford and his contemporaries would have considered quite impossible.

The London slums are still bad enough, but they are nothing to those of the nineteenth century. Gone are the days when a single room used to be inhabited by four families, one in each corner, and when incest and infanticide were taken almost for granted. Above all, gone are the days when it seemed natural to write off a whole stratum of the population as irredeemable savages. The most snobbish Tory alive would not now write of the London working class as Mark Rutherford does. And Mark Rutherford—like Dickens, who shared his attitude—was a Radical! Progress does happen, hard though it may be to believe it, in this age of concentration camps and big beautiful bombs.

December 1943