This Day in Labor History: October 10, 1842

On October 10, 1842, a planter Eli Capell noted the precise amount of cotton picked by each of his slaves in his logbooks. This seemingly minor moment is in fact a really useful way to understnad a core part of our labor history–how planters used modern capitalist techniques to control slave labor.

Slavery built American capitalism. This seemingly obvious statement was seen as totally offbase for a long time. For many years, part of the southern myth about the Civil War was that the big evil capitalist state in the North fought the Civil War against the South as a war of capitalism against a non-capitalist society. This had a ton of play on the left–even in the early 2010s when I started to write about this stuff online, you’d get old leftists who continued to argue it. They would argue that the North didn’t care about slaves, it was all about capitalism. This is absolute nonsense, not necessarily about the North caring about slavery but that this was a war of capitalism against a non-capitalist state. Slavery and capitalism were deeply interlinked. Of course it was the cotton from the southern plantations that fed the northern (not to mention British and to a lesser extent French) mills. But the ties ran so much deeper. Naturally, lots of northern factory owners invested heavily in southern cotton plantations and plenty of southern cotton planters invested in northern factories. Again, this should be an obvious point–of course different forms of integrated business practices would exist then as they do today.

But the connections are really so much deeper than that. Slave owners were supreme capitalists. Yes, they invested in human property rather than other forms and so maybe that’s why so often they are seen as a different kind of business operator. But they needed to maximize their profits too. Maybe because northern stereotypes see southerners as a bunch of dumb reactionary crackers, it gets in the way of also viewing southerners as what they were–pioneers of American accounting methods to increase their slave-created profits.

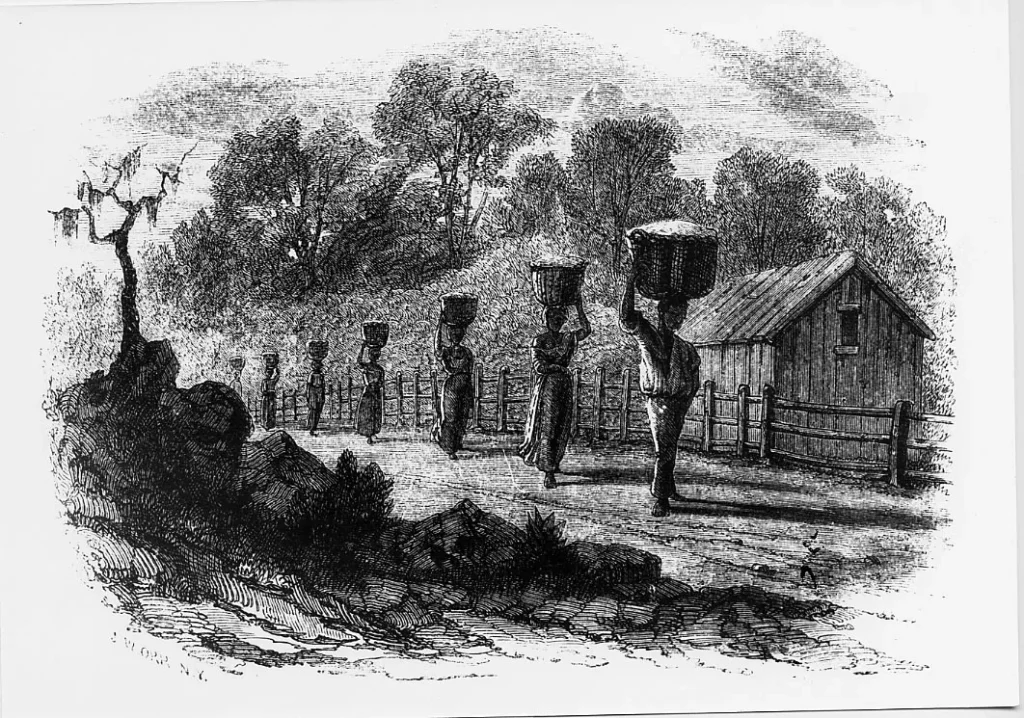

Eli Capell owned Pleasant Hill Plantation in Amite County, Mississippi. He was a master of accounting methods. He was super pumped on October 10, 1842. See, every single day he measured precisely how much cotton each slave of his had picked and on that day, they set a record with 2,545 pounds, each slave picking at least 100 pounds. For him, modern scientific forms of management was how he was getting his slaves to pick more. Of course the whip was a big part of that. Capell had built his plantation from a small operation he inherited from his father to a big plantation with 80 slaves. His carefully kept account books that recorded daily production from 1842 to 1867 still exist.

The thing is about these old arguments about capitalism and the Civil War is that the evidence is overwhelming that southern planters paid far more attention to labor productivity than northern employers. They were very explicit about figuring out just how much work each of their slaves could do and then driving them to do that every single day. In short, the whip became not just some racist tool to punish, but as a core precursor of the labor management techniques that spread throughout American workplaces as the 19th century moved on. The whip itself could not be used in the factory, but there were plenty of ways to exploit labor without it technically being slavery, as the South would discover later.

One of the key figures here was a man named Edward Affleck. He was a former bookkeeper for the Bank of Scotland who moved to Mississippi for a new start in 1832. He started planting cotton and introduced his friends to the accounting methods he had learned back in Scotland. They readily adopted his ideas and vastly improved their financial accounting through his methods, which he soon published. Capell was one of those who bought Affleck’s books. There were several, depending on plantation size. Affleck encouraged planters on everything from interest rates to keeping track of doctors’ visits to slaves.

What’s more, while there were many, many small plantations before the Civil War that would or could not adopt Affleck’s methods, the largest planters–who obviously were the most influential–often did and this helped spread the idea of maximizing production from labor by using the most modern methods, always backed up with physical violence of course. Just how little can we feed our slaves? Just how many hours can we force them to work before they die in the field? New breeds of cotton that vastly increased boll production made these questions all the more salient for planters and contributed to the horrors of slavery. Affleck’s methods suggested multiple weighing of cotton during the day to correct for slaves slacking off if that was what was happening, for example, which meant more times during the day for beatings and punishments.

If you were going to use modern scientific management tactics to figure out just how much you could drive out of slave, you were going to then try to make that maximum a daily standard, just as you would a horse or cow. The difference for many planters between the horse and the human though is that as much as they worked to deny the humanity of their human property, they were generally not raping heir farm animals and having children with them as they were their humans. Trying to turn humans into animals only went so far and of course sex slavery was a huge part of the slave system, which we should talk more about.

What’s interesting is that the surviving accounts from this period from planters are much more sophisticated than surviving account books from northern factory owners. In fact, pretty sophisticated accounting methods were already being used by Caribbean planters as early as the 18th century. In short, capitalism wasn’t created in antipathy to slavery. It was created by slavery. Being a planter meant a much greater investment in complex systems of capital than running a factory. The smarter and more sophisticated planters realized this and acted upon it.

I borrowed from Caitlin Rosenthal’s “Slavery’s Scientific Management: Masters and Managers,” in Sven Beckert and Seth Rockman’s Slavery’s Capitalism: A New History of American Economic Development to write this post.

This is the 578th post in this series. Previous posts are archived here.