When The Center No Longer Holds

The story of how centrist folk facilitated Hitler’s rise has been around for a while. What harm could he do? Throw him a bone, and he’ll settle down. And above all, we must avoid the socialists and Communists! Can’t give them a slippery slope!

Here’s yet one more succinct account, from Daniel Ziblatt, a scholar of democracy.

On March 23, 1933, inside a dimly lit chamber filled with the stale scent of cigar smoke, Ludwig Kaas tried to convince himself he was making the right decision. A Catholic priest and the leader of Germany’s establishment Center Party, he stood at a crossroads. For several years, his party had sought to block Adolf Hitler’s rise. But in 1932, Hitler’s National Socialists (Nazis) became the largest force in parliament, and in January 1933, Hitler became chancellor. As he moved to consolidate power, the Center Party had become the last remaining obstacle to his bid for total control over Germany.

Hitler had introduced the Enabling Act, which would allow him and his cabinet sweeping powers to rule by decree, thereby dismantling democracy at its core. The act needed a two-thirds majority to pass. The Social Democrats—the only other significant group of parliamentarians that still fundamentally supported democracy—were too few to stop it alone. If the Center Party also resisted, it could block the act’s passage.

But Kaas hesitated. He feared what would happen if his party defied the Nazis. Would it survive? Could democracy endure if his party resisted? Hitler’s storm troopers had already begun arresting political opponents. Kaas convinced himself that his best option was to cooperate—to work within the new reality rather than be crushed by it. “We must preserve our soul,” he told his colleagues, “but a rejection of the Enabling Act will result in unpleasant consequences for our party.” The act passed, 444 to 94, opening the path to Hitler’s dictatorship.

Ziblatt’s conclusion:

Democracy rarely dies in a single moment. It is chipped away via abdication: rationalizations and compromises as those with power and influence tell themselves that yielding just a little ground will keep them safe or that finding common ground with a disrupter is more practical than standing against him. This is the enduring lesson of Weimar: extremism never triumphs on its own. It succeeds because others enable it—because of their ambition, because of their fear, or because they misjudge the dangers of small concessions. In the end, however, those who empower an autocrat often surrender not only their democracy but also the very influence they once hoped to preserve.

The whole thing is worth reading, if you can. I’m not sure if there’s a paywall.

I’ve been thinking of another historical analogy, this one in the United States. The last time a political party collapsed seems to me to have a number of similarities with today’s situation. Like the Democrats, the Whigs couldn’t get their act together to oppose an anti-democratic movement.

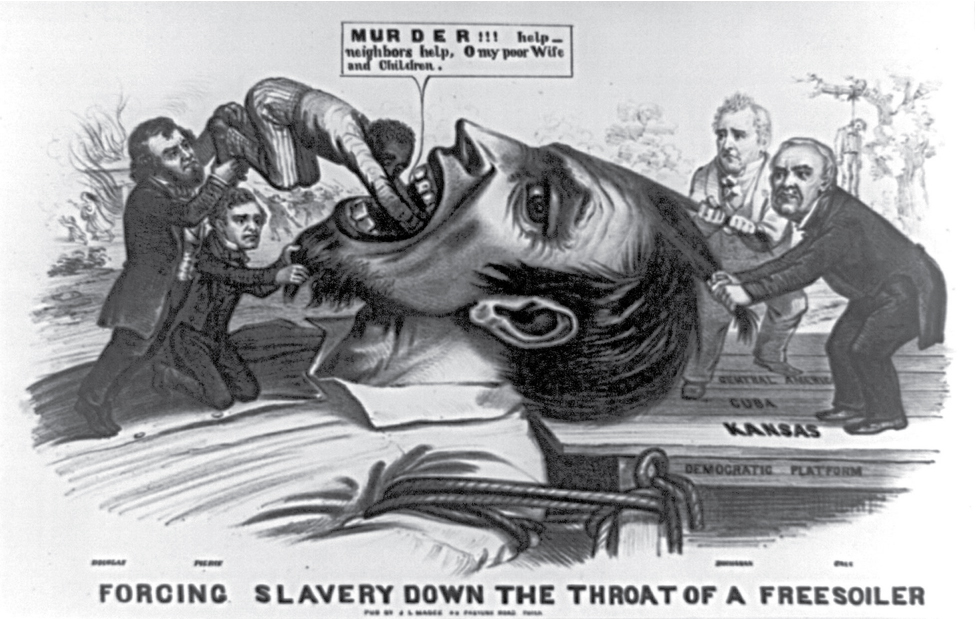

As the United States expanded across the continent, the slavers wanted to extend slavery to all the new territories and states. The Democratic Party represented them and yes, they were the baddies. Since 1964, the Republicans have followed Nixon’s Southern Strategy to take their place. The Whig party was their opposition. The Whigs were a relatively new party, a difference from today’s Democrats.

Slavery had been argued since the beginning of the Republic and earlier. The economies of the southern states depended on it, and it was a cultural divide as well. The Democrats were firmly in favor, so it was left to the Whigs to oppose it.

The Whigs gave in to the Compromise of 1850, which included the Fugitive Slave Act, which required people in free states to surrender escaped enslaved people, if captured, to their owners. But it was a compromise! On the other side, California entered the union as a free state, and whether several other territories were to be slave or free was left undecided. So the compromise was a trade of enslaved people’s rights for California and kicking the can down the road.

The Fugitive Slave Act increased polarization and public sentiment against slavery in the North. The Kansas-Nebraska Act of 1854 exacerbated the situation by allowing the two new states to decide on slavery by popular vote. The Whigs strongly opposed the act, but it was passed by Congress.

A new political party, the Republicans, was formed of the radicals who wanted to abolish slavery with no qualifications and those more tepid. A tension continued between these two groups, but the Democrats were sufficiently extreme that the tension pulled toward the anti-slavery groups rather than a “moderate center,” as some of today’s Democrats like to think of themselves.

Repeat: With a strong anti-democracy party, its opposition gravitated toward the more radical position of ending slavery in all states and won through the addition of the 13th, 14th, and 15th Amendments to the Constitution after the Civil War.

With polatization rising, the Whigs could not hold their compromised position together. People who opposed slavery joined the Republican Party in the North and several smaller parties in the South.

Abraham Lincoln ran for President as a Republican. He walked a middle road on slavery at first, but as the war went on became convinced that slavery must be ended.

We are in circumstances as extreme as those of the 1850s. The Republican political party is happy to impose a dictatorship. The leadership of the Democratic Party, like the Whigs, insist on finding compromises. The base of the Democratic Party, like the uncompromising Radical Republicans, insists on hard opposition. No party like the 1850 Republicans is forming, but some of the Democratic Party leadership and assorted mavericks like Zohran Mamdani are moving in the radical direction.

Hitler won. But so did the Radical Republicans. It’s up to us.

I used Wikipedia and my own knowledge of this history as my quick historical resource. I’d go deeper into sources, but this is a blog post. Other sources welcomed in the comments.