Look at the Lies We’ve Swallowed…

My colleague Joseph Young (formerly of Political Violence at a Glance) has a new piece at CSIS talking about civil war:

Q2: What causes a civil war?

A2: Most literature on civil wars tends not to find ideology or political polarization as a primary catalyst. Identity is rarely the cause of this kind of conflict. Rather, the causes of civil wars are often tied to low GDP per capita, a weak central government, safe havens (i.e., harsh terrain where rebels can hide), access to natural resources that rebels can take, and other structural concerns. Furthermore, many civil wars need a cycle of violence in which states repress citizens, leading to dissent and even armed opposition. Even this cycle often tends to lead to protest movements rather than rebellions.

Seen in this light, there are few structural incentives for a second U.S. civil war. The economy is strong, the U.S. government and military are capable, and no group is trying to secede or annex territory to secure natural resources. Instead, the United States has social media and other voices amplifying differences, leading to a sense of polarization. For this polarization to evolve into a civil war, based on literature and hundreds of years of history, it would likely require years of organized violent conflict between the government and a resistance group, a major split or defections at the upper levels in the military, and likely either an economic collapse or major authoritarian consolidation of power.

Q3: How does recent political violence in the United States compare to historical patterns?

A3: A people “numerous and armed” are bound to have a history defined by periodic waves of political violence and civil conflict. From the 1791 Whiskey Rebellion to Bleeding Kansas and the U.S. Civil War, there were numerous small and larger-scale violent episodes in the formation of the nation.

The United States did fight a bloody Civil War that was a secessionist variety that included large splits in the military, battle deaths on both sides that were well above 1,000 people, and lasted four years. The end of the Civil War led to a decisive victory by the North, a common outcome in civil wars. Reconstruction followed, but political violence—particularly in the South, targeting Republicans and newly enfranchised African Americans—remained widespread.

The 1960s and early 1970s, another volatile political time period, saw daily incidences of political violence on college campuses, the bombing of the U.S. Capitol by the Weather Underground, and the assassinations of President John F. Kennedy, Martin Luther King Jr., and Robert F. Kennedy.

All of these periods likely had more heightened levels of polarization and violence within U.S. society than today. One period that may be more similar to ours is the early 1900s. On the left, anarchists perpetrated attacks like the Wall Street Bombing in 1920, which killed 38 people and injured hundreds more. President McKinley was killed by an anarchist in 1901. During this period, the United States also witnessed a series of mail bombings in 1919 that targeted wealthy industrialists, including John D. Rockefeller. While these high-profile events were tragic and deadly, other violence during this period was from the far-right, including a major resurgence by the Ku Klux Klan in the 1920s. Additionally, the Palmer Raids and First Red Scare were organized repressions by the U.S. government against immigrants and suspected radicals. While these events were tragic and violent, this period was never close to what scholars or observers would characterize as a civil war.

Q5: So, is the United States headed toward another civil war?

A5: Based on data, history, academic literature, and scholars who study political violence, the United States is not headed towards a second U.S. civil war. That does not mean the nation will be spared episodic political violence and other unnecessary loss of life. It does mean that the likelihood of a large-scale battle between the government and an organized rebel group that goes on for years, and claims thousands of lives on both sides, is highly unlikely.

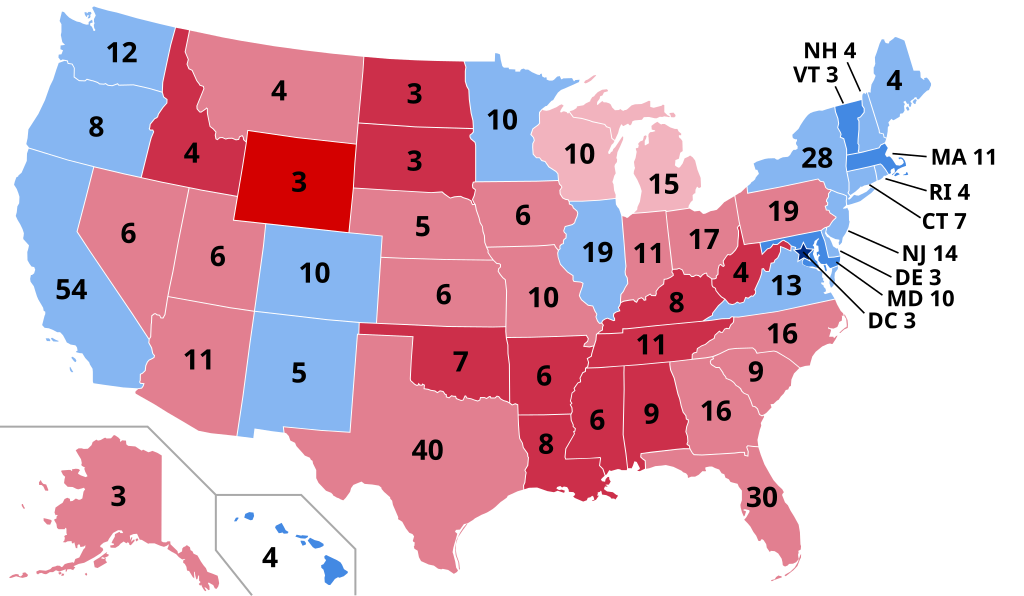

This puts me in the mind of Paul’s post on civil wars and American disunity. I doubt it will surprise many to find that I agree completely with the second perspective (I believe from Christopher Bird) that the character of contemporary political division makes secession and civil war on 1865 lines pretty much unthinkable. As I’ve argued many times before, political conflict in the United States has much less to do with the imaginary lines that divide Red and Blue states than with the much, MUCH messier urban-rural divide. The Confederacy could possibly have been a coherent political and economic unit; Blue America and Red America can not be disentangled so easily, even if the foundational issues were more dire than they are at the moment.

But of course “we’re probably not on the verge of a Second Civil War” doesn’t mean that we’re not on the road to a period of increased political violence and of authoritarian consolidation. These latter, rather than a replay of 1862, are the real threats facing the country.