Erik Visits an American Grave, Part 1,915

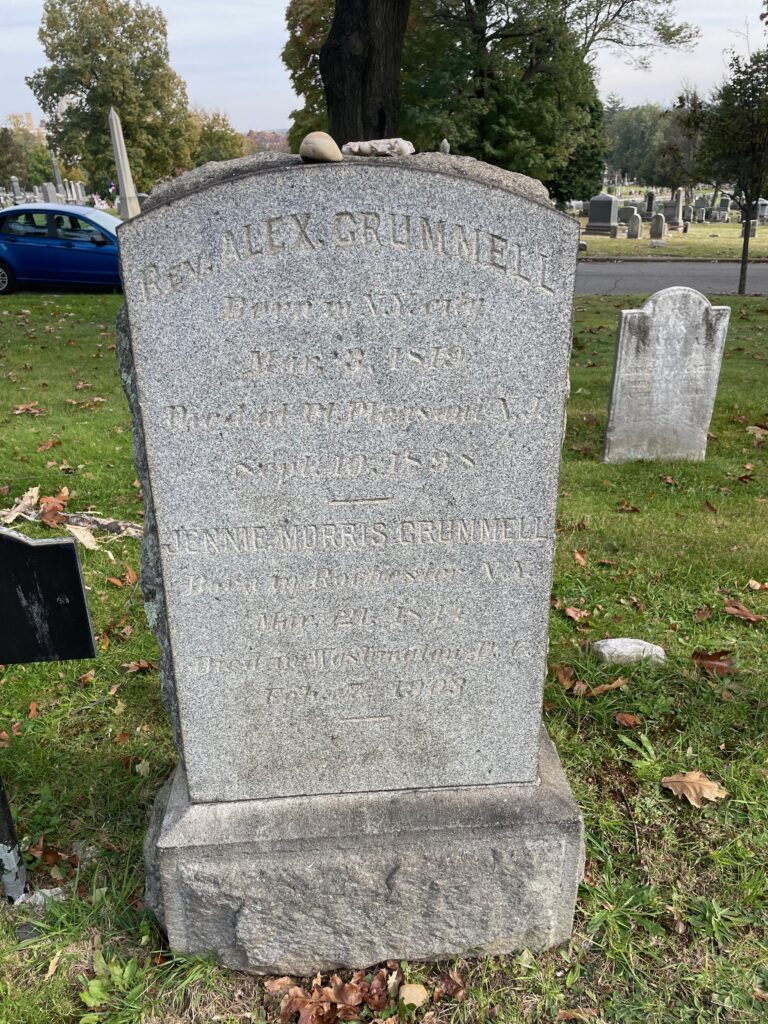

This is the grave of Alexander Crummell.

Born in 1819 in New York City, Crummell grew up in the free Black world there. Remember though that New York was the center of northern slavery and there were still slaves in the city and in the Hudson Valley when he was born. His father was a freed slave. His parents were involved in the abolitionist movement and taught their children of the evils of slavery and their duty to fight this horrible institution. In fact, the city’s first Black newspaper, Freedom’s Journal, was published inside their home. He attended the best schools he could in New York and then was sent to New Hampshire, where a Black boarding school had opened. This of course led the good whites of New Hampshire to burn it down. Live free or die.

That burning led Crummell to the Oneida Institute, where a lot of abolitionists had studied. He decided while there to become an Episcopalian minister. He went to Yale for further study in 1840 and was ordained in 1842. He had a church in Providence. I should find out where that was. But there were so few Black Episcopalians and whites were racist so wouldn’t be served by a Black minister. This leads to me another point, which is that since the only people who become priests these days are Africans, we are starting to see these racist whites who attend Catholic Churches every week in the United States have to deal with Africans giving them the host and confessions. In any case, Philadelphia offered him a church, but on a segregated basis. He rejected that offer.

Crummell ended up going to England, first to raise money for his churches, but then to speak about abolitionism and then to study. In fact, he became the first known Black person to graduated with a degree from Cambridge, though he is known to not be the first Black person to study there.

Crummell became deeply invested in Black migration out of the United States and to Africa. This was never really very popular in Black communities, but the idea to get Black people out of United States and to the new nation of Liberia was popular among a lot of whites and had some understandable appeal to some Black folks. The problems became obvious once it actually was put in motion–tropical diseases killed a lot of migrants back to Africa, those who survived legitimately thought they were there to convert the savage Africans and so treated the locals like a colonized people and caused a ton of resentment that still resonates in that country today, and of course whites were not going to see Liberia as equal to a white country anyway. Plus, most Black people considered themselves Americans and wanted equality at home, not to go to some country they did not know.

But for someone such as Crummell, Liberia meant freedom from whites and you can see why that would be appealing. Crummell moved to Liberia in 1853. He would stay there for most of the next twenty years, engaged in both the creation of a free state for Black Americans and the conversion of west Africans to evangelical Christianity. In the end, Crummell wasn’t very successful on either end of this project. Ideas for moving back to Africa continued after the Civil War, so that event didn’t make that huge of a difference here. Whether before or after the war, the vast majority of Black people had zero interest in returning to Africa. The fight was here, not there. Moreover, Crummell’s condescension toward Africans as savages who needed civilization did not play well with everyone. Of course most Black Americans were Christians, broadly defined, in the 1850s through the 1870s, but the inherent inequality in his vision of Africans did not go totally unchallenged, even if people would have broadly agreed that converting people to worshipping Christ was a good thing.

Even compared to other Black advocates of going to Africa though, Crummell really embraced the anti-African language. Some scholars have suggested that doing so was advantageous in dealings with the white funders of back to Africa projects. Perhaps that’s true. Like Booker T. Washington, it can be difficult to tease out his actual beliefs compared to what he needed to say to whites to maintain the funding and his status. He would state some pretty bad things though, such as denying that west Africans even had a history, talking of “the long, long centuries of human existence in Africa…Darkness covered the land and gross darkness the people.” Ugh. He also subscribed to some of the geological and environmental determinism rising in this era, saying that the reason for the Africans’ backwardness was that the Sahara Desert isolated them from the great advances of European civilization.

In fact, Crummell knew that things weren’t going that well among his friends who initially had come to Liberia. He started to criticize the corrupt leadership in Liberia and how they treated Africans, which eventually led him to leave Liberia, fearing for his life.

Fundamentally, Crummell was a Black nationalist. He was forecasting the work of people such as Marcus Garvey decades later. He simply did not believe that Black Americans could have anything like equality in the United States and that the only hope was to leave the United States instead. Again, he was filled with the cultural prejudices of the day created by whites toward Africans and was far from a perfect person himself in articulating this stuff, but it’s easy to see where he was coming from, He wasn’t the first person to articulate this stuff and it wasn’t that far of a distance from him to the Black Panthers or the Nation of Islam in the late 20th century.

Crummell returned to the United States in 1872. He started a new church in Washington, D.C. and then another in 1875. He would remain involved in that until his retirement in 1894. He published a bunch of his sermons over the years. He then taught at Howard University for a couple of years, from 1895-97. He still pushed for Black pride and Black self-determination and spent quite a bit of his energy in his later years creating the American Negro Academy, which was intended to provide financial and institutional support for Black artists and intellectuals. He founded it in 1897 and it continued until 1928, so not a bad run. It became closely associated with W.E.B. DuBois and his ideas of the Talented Tenth that would lead the civil rights movement in the future.

Crummell naturally did not live to see much of this, as he was pretty old by the time it opened. He died the next year, in 1898, at the age of 79.

Alexander Crummell is buried in Cypress Hills Cemetery, Brooklyn, New York.

If you would like to visit other 19th century African Americans, you can donate to cover the required expenses here. Eli Baptist is in Springfield, Massachusetts and Lucy Sprague is in Rochester, New York. Previous posts in this series are archived here and here.