This Day in Labor History: May 10, 1972

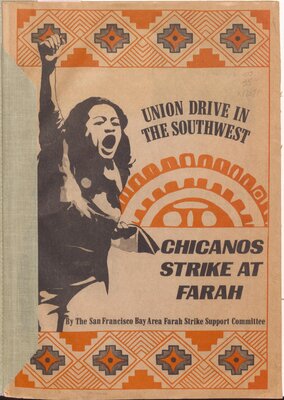

On May 10, 1972, the Farah clothing strike in El Paso began. This almost all-Latino workforce, mostly women, were on the front lines of labor activism in the early 70s. This became a nationally important strike and while the textile industry was not to last in Texas for very long, was an important moment in the struggle for decency in the ever-exploitative apparel industry as well in connecting the labor struggle to the Chicano struggle.

Willie Farah grew up in a Lebanese immigrant family that had settled in Las Cruces, New Mexico. His father had invested heavily in building textile factories in El Paso, taking advantage of the cheap labor coming out of Mesxico in the aftermath of the Mexican Revolution. His sons took over the factories, led by Willie. They opened more, including in San Antonio. They were particularly active in getting contracts to make blue jeans by the 70s, which had become the uniform of the youth and in many ways remains the uniform of Americans today. The factories also made a lot of slacks. Farah saw himself as a welfare capitalist who would engage in charity for his workers, but he wasn’t really. Sure, he would give out a free turkey on Thanksgiving. My dad’s plywood mill used to do this, as if that was enough. Then they would give out another free turkey on Christmas, meaning we ended up eating turkey for like six straight weeks. Given my well known disdain for this lowest and driest of meats, you can imagine this did not endear me to this form of welfare capitalism. More importantly, Farah was deeply anti-union and did not hide it. For him, unionism was an assault of his right to do whatever he wanted with his workers and since he was so invested in his own righteousness as an owner, how dare they attack him!

Unionization at Farah began in 1969, when the mostly male cutters joined the Amalgamated Clothing Workers of America. This soon spread through the factory and other units joined the union. While the cutters were mostly men, most of the other workers were women, about 85% of Farah employees in Texas. Given the low-wage nature of the work, most were Mexican-Americans and Mexicans. In 1972, workers from Farah’s San Antonio factory came out to El Paso to engage in a solidarity action with their union brothers and sisters. Farah fired six of them. Five hundred of his San Antonio workers struck to protest. El Paso workers voted to strike as well on May 9 and walked off the job on May 10. The El Paso workers became the centerpiece of the strike.

This became a two-year long struggle that was one of the most important labor actions of the era. The AFL-CIO came out pretty big in favor of the workers, calling for a national boycott of Farah products. They did a lot of fundraising, building up strike funds to keep the workers comfortable with being off the job. This entire action very much and quite consciously built upon the success of the United Farm Workers in the previous decade and the idea that the new frontier of labor organizing was among Mexican-American workers. That population had largely been left out of the bigger organizing victories of the 30s and 40s and were in fact pretty ready to organize.

The strike of course divided El Paso. First, Anglos (and this is what whites are known as in this part of the country, up into New Mexico) were almost all opposed to the strike. It threatened their racial hierarchies after all. Some leaders in the Mexican American community were also often opposed to the strike. Worker activism has often made leaders who might otherwise be progressive very uncomfortable. That was especially true in the 1970s, as people previously excluded from major power now could win it and saw worker activism as a threat, such as Maynard Jackson in Atlanta. A similar dynamic played out in El Paso. But a local priest named Father Jesse Munoz did a ton of critical solidarity work for the strikers in El Paso and kept large parts of the community on their side. Our Lady of the Light Catholic Church became the unofficial strike headquarters.

It wasn’t that hard to find replacement workers. Many were brought north from Mexico and could just return to Ciudad Juarez at night. But the boycott bit. Moreover, the workers became more confident as time went on, training in public speaking and becoming more broad-based activists. There was a larger hope here that by organizing in El Paso, the garment workers could move across the border and organize the growing maquiladoras that had sprung up since the creation of the Border Industrialization Program in 1965 that had lured American companies to move their operations to the Mexican side of the border.

Finally, in 1974, the National Labor Relations Board came down wholly on the side of the strikers. The decision absolutely lambasted Farah, in a way that rarely happened, even then. It accused Farah of “flouting the [National Labor Relations] Act and trampling on the rights of its employees as if there were no Act, no Board, and no Ten Commandments.” It ordered Farah to reinstate all the fired workers and quit getting in the way of union organizing. In February, he reluctantly recognized the ACWA as the legitimate bargaining agent of his workers. The workers soon won a contract that included all the things one would want–pay increases, greater job security, grievance procedures, seniority rights, all the normal stuff.

The longer-term story was less happy for both Farah and the ACWA. The ACWA talked a big game about how this was a revolutionary moment, but it really wasn’t. It was a single victory. For Farah, the strike really did hurt his business. He made other mistakes too that had nothing to do with the union but which undermined the company, such as missing out on newer fashion trends. The ACWA did sign up a lot more workers once they weren’t scared of losing their jobs, but the two year strike and boycott was tremendously expensive to run and the union probably never broke even on it. They did not successful move into the maquiladoras. The workers were not very happy with the contract, saying that the national union leadership sold them out for far too little money, which absolutely can happen. Moreover, many of the original workers moved on to better jobs. It’s not like working in an apparel factory is that great even with a union contract. The problem though is that when workers are not committed ot the job, it becomes easy for the company to retake power and that’s what happened here.

I borrowed from Alicia Schmidt Camacho, Migrant Imaginaries: Latino Cultural Politics in the U.S.-Mexico Borderlands and Jefferson Cowie, Stayin Alive: The 1970s and the Last Days of the Working Class, to write this post.

This is the 562th post in this series. Previous posts in this series are archived here.