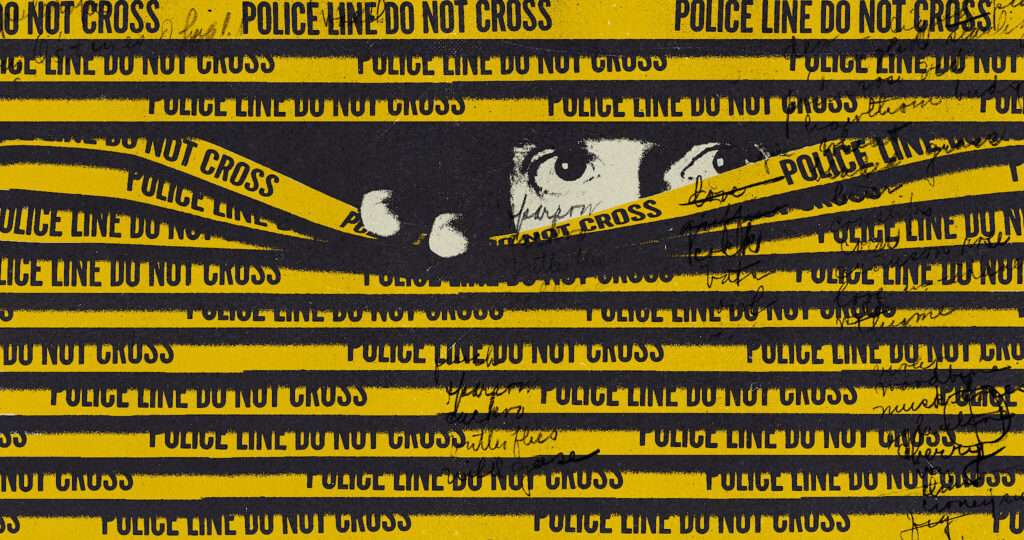

True Crime as Exploitation of Suffering

I’ve talked before about my disdain for true crime as a genre. In short, it is gaining entertainment out of people’s actual suffering, which seems abominable to me. I get it if you are reading about a heist or something, but when we are talking kidnapping and murder and sexual violence…why the hell would you read/listen/watch that? Given my preexisting predilections on the matter, I was happy to read this op-ed from Polly Klass’ sister, telling people to knock it off.

Though the media frenzy should have ended there, it only intensified, fueling a political climate primed for reactionary reprisal. Polly’s kidnapping from our middle-class, white, suburban community triggered a national outcry for punishment and retribution.

In the next few years, true crime began to morph into the media obsession it is today. Last year, The Hollywood Reporter alerted its readers to “30 True-Crime Series to Binge Right Now.” As I write this, nearly half of Apple’s top 20 podcasts in the United States are devoted to true crime, and the internet is saturated with recommendations for the best new true crime books to read.

One might argue that this genre honors victims and those who solved or sought to solve the cases. However, as a survivor whose tragedy continues to be exploited by creators of true crime stories, I know the personal pain of this appropriation, as well as how coverage of these high-profile cases can contribute to broader injustices. The exploitation of victims’ stories often carries a steep cost for their families as their tragedies are commodified and their privacy repeatedly violated for mass consumption.

In 2022, for instance, the release of “Dahmer — Monster: The Jeffrey Dahmer Story” on Netflix caused profound distress among many family members of Dahmer’s victims, who felt that the show was profiting from their pain, misrepresenting actual events and retraumatizing those who had lived through the horror of Dahmer’s crimes.

On top of those harms, the stories that don’t fit with true crime’s cultural emphasis on white female victimhood too often go untold.

Before my sister’s murder, a version of what has become known as the three-strikes law was proposed in California. The measure called for a sentence of 25 years to life for almost any crime, no matter how minor, if the defendant had two prior convictions for crimes the law designated as serious or violent. The measure was initially seen as so unjustifiably harsh that it was swiftly rejected by the State Assembly’s Public Safety Committee.

But Polly’s case changed things in California. In the wake of our highly publicized tragedy and the murder of 18-year-old Kimber Reynolds the previous year, politicians were able to leverage the grief of some victims’ family members to revive their proposal, swiftly passing one of the harshest sentencing laws of the past century.

….

Although none of the content creators who went on to dramatize my sister’s murder have ever asked me for consent, a few have reached out in recent years to ask me for my memories. In so doing, they often excitedly bombarded me with details about the case I didn’t want to know, causing an onslaught of post-traumatic stress. I can recall the subsequent weeks that I spent lying awake at night, trying to quell the panic in my nervous system. How could I explain to these writers and producers that my memories of Polly are the only things I have left of her that haven’t been exploited or extracted for public consumption? How could I convey the traumatic upheaval these books and shows could set off in my life and the lives of my loved ones? Would our pain matter to these people who claimed to care so much about justice and the welfare of victims?

An unfortunate result is that packaging trauma as entertainment ignores the diverse needs of victims. Whereas some true crime audiences may view victims and their families as a monolith crusading for punitive sentencing, a 2022 report by Alliance for Safety and Justice, an organization I work with, reveals that most of the survivors it surveyed favored rehabilitation and prevention over punishment. To truly dismantle cycles of harm, it is imperative to amplify survivors’ stories on their own terms and earnestly embrace the safety solutions they are pioneering in their communities.

On our path to healing, my sister Jess Nichol and I started “A New Legacy” in memory of Polly, a podcast of conversations with community organizers and people harmed by three-strikes laws to explore how we can replace systems of punishment with systems of care. I also am a producer for the “Crime Survivors Speak” podcast, on which we amplify the insights and experiences of members of Crime Survivors for Safety and Justice, a survivor organization with nearly 190,000 members, to reduce incarceration and increase investments in crime prevention, trauma recovery and rehabilitation. Through this work, I’ve learned that when you truly listen to survivors, your heart rate should never be speeding up; it should be slowing down. This is how new dimensions of justice and healing become imaginable.

I mean, really, true crime as entertainment is a moral cancer. And before someone mentions football, note that people play football consensually and, today at least, they get paid for it.