Saving a sport

The Times recently published an op-ed arguing that the rule changes MLB instituted during the last off-season requiring in various ways players to play baseball instead of engaging in self-indulgent dicking around ruined the “poetry” of baseball. This is extremely stupid, and precisely the illogic and misguided nostalgia (the way baseball was played in 2022 was not the way it had been played for most of its history.)

Jayson Stark summarizes how effective the changes were:

Does anyone miss getting home from the ballpark at 12:45 a.m.? Does anyone miss watching those batting gloves get adjusted after all 300 pitches, every night?

If you do, you have way too much time on your hands. If you don’t, you can thank the pitch clock — 15 seconds between pitches with no one on base, 20 seconds with runners on. After watching the clock tick away for a season, do we even have to ask: Does the pitch clock work? In truth, it’s hard to think of any rule change in recent memory that accomplished exactly what it was designed to accomplish as well as this one did.

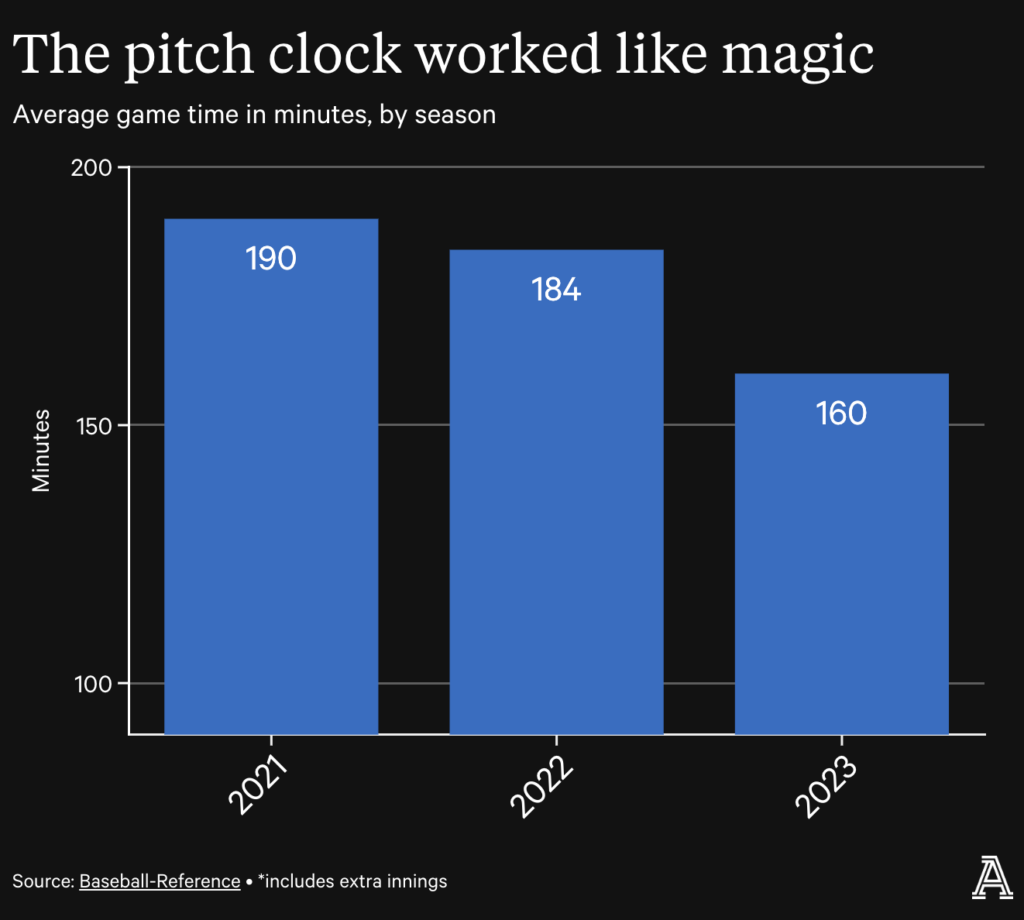

Average game time: Who knew it would be this easy to chop a half-hour’s worth of dead time off every game? But that’s the exact magic trick the clock has pulled off. Check out the time of the average nine-inning game over the last three seasons:

But average game time doesn’t even fully tell this story. There’s also this …

Games of 2 hours, 15 minutes or shorter — In 2022, there were 13 nine-inning games that short all season. In 2023? That number went up slightly … to 170. In other words, there used to be one game that quick every two weeks. This year, there was, essentially, one every night.

Games of 2:30 or shorter — But let’s keep going. In 2022, there were 84 nine-inning games all season that lasted 2 1/2 hours or less. In 2023, there were 678.

Games of 3:30 or longer — How routine did the 3 1/2-hour game used to be? So routine that in 2022, there were 232 nine-inning games that lasted at least 3:30. This year, there were nine — four of them in September, after rosters expanded. And in seven of those nine, at least 16 runs were scored. So at least there was a good excuse. But one more thing …

We’ve killed the four-hour game! How many nine-inning games lasted four hours or longer in 2023? That answer is … zero. That’s down from 39 two years ago and 19 in 2022. But even if you include extra-inning games, there were only six four-hour games over this entire season — and every one of them lasted 12 innings or longer.

Even among people who weren’t necessarily opposed to the rule changes, there were arguments that pitch clock violations might “decide” a game and perhaps should be more loosely enforced in late innings. This was a terrible idea — the best way to get players ot adapt was to enforce the rules strictly and without arbitrary exceptions, which would ultimately lead to a small number of violations as players got used to the pace. Again, MLB got this right, and want to guess how many pitch clock violations there were in the entire postseason?

The pitch clock turned invisible in the World Series: During the World Series, Fox never popped the ticking pitch clock onto its screen. Not for one pitch. Did anyone even notice? In a possibly related development, there wasn’t a single violation during the World Series. There were only seven violations in the postseason. And of the 23 postseason games NL teams took part in, there was just one violation. Amazing.

Was there any better indication of what a non-topic the clock was by October than that invisible TV pitch clock? We’ll vote no.

And even just looking at the reduction in game times in isolation is misleading, because the shorter games contained more action:

Luckily, that was not all these rule changes wrought. Instead, baseball in 2023 was a significantly more entertaining mix of the two qualities every sport aspires to:

More action. … Less dead time.

How much more action was there? We’re talking about …

• Over 1,600 more runs than the year before.

• Nearly 1,300 more stolen bases.

• More than 1,100 more hits.

• Nearly 1,500 more baserunners (a formula based on hits plus walks, minus homers).

• But there wasn’t nearly as much waiting around for all that action to unfold. The average time between balls in play dropped by nearly 30 seconds — from 3 minutes, 42 seconds last year to 3:13 this year. That’s a level baseball hasn’t seen since 2009, according to Baseball Reference.

And, most importantly, the rule changes were popular with fans and returning fans and new fans:

Was there a 100 percent approval rating for all of this in Year One? Ha. We don’t need to go there. But you know who was all in — based on attendance data, local TV ratings and the significant increase in people watching entire games on their favorite mobile devices? The customers. And that’s telling the rule-change architects that they seem to be cruising down the right lane of the sports highway. Finally.

The reason that arguments against the rule changes are almost always couched in metaphysical abstractions is that if they’re made more concrete they’re self-refuting. Nobody thinks that a batter stepping out to adjust his gloves or a pitcher standing on the mound doing nothing is entertaining. Nobody really thinks that a pitcher throwing 8 half-assed lobs to first base is a more exciting play than the stolen base. Nobody actively decided they wanted the game played this way — it was the result of ill-conceived laissez-faire on the part of “traditionalists” and “purists,” But as Bill James pointed out 20 years ago in an essay I wish had been more immediately influential, for most of its history baseball had a clock — the sun, and then a generation of players and umpires who learned the game when it had to be played at a brisk place to be finished on time.

These rule changes would be eminently justified simply on the grounds that they make the game better, But the traditionalist argument is nonsensical even on its own terms — the rule changes make the game more like it has been played for most of its history, not less. I haven’t had a lot of occasion to praise MLB leadership in my lifetime, but these changes were an inside-the-park home run.