This Day in Labor History: May 12, 1933

On May 12, 1933, the Agricultural Adjustment Act went into effect. AAA would have a dramatic and permanent transformation on the history of farm labor in America. Whether this was a good thing or not depends on your perspective, but from the perspective of the sharecroppers thrown off their land, it most definitely was not a good thing. They fought for their rights, the best they could. But in the end, the government had no real interest in helping these impoverished farmworkers and mostly did not.

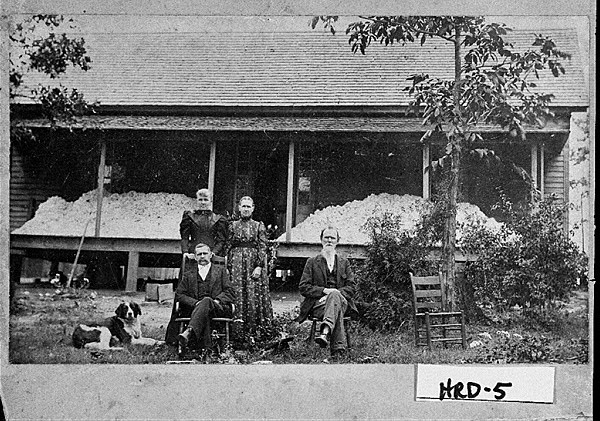

Soon after the Civil War, sharecropping became the norm in southern farm labor. After the Civil War, southern planters, and to a growing extent northern owners of southern land, wanted to tie Black labor to the land. After all, the entire point of slavery was to create a permanent unpaid labor force. Could that be replicated? Freedpeople had very different thoughts. They wanted to be subsistence farmers working for themselves on their own lands. They did not want gang labor, they did not want to grow cotton, and they mostly wanted nothing to do with white people. They simply would not accept a return to slave labor conditions, even with some kind of pay.

Sharecropping thus became something of a compromise. That does not mean it was not a horrible, exploitative system. It was. But at least on a daily basis, Black farmers had more control over their lives. They might not own land, but at least they could build their own cabin away from the plantation house and escape the daily watch of the white overseer or landowner. The debt burden upon these farmers–backed with violence if they complained–had mostly tied that Black labor to the land as whites wanted.

By the late nineteenth century, sharecropping increasingly had become something drawing in poor white farmers too. There was little room in the pre-Civil War South for everyday white farmers and this was a long critique by the North about slavery. After all, for most who opposed slavery, their top concern was not what it did to Black people. It was what it did to white people. Plunging cotton prices and growing debt loads undermined whatever limited power many white farmers had in the economy and soon many were driven into sharecropping. This helped fuel the farmers’ uprisings of the 1880s and 1890s into the Farmers Alliance and then the Populist Party, but that was short-lived.

The Great Depression started a long time before 1929 in the farming community. The expansion of agricultural production during World War I, which was actively encouraged by the Wilson administration as part of its propaganda campaigns to win the war, combined with the growth of expensive machinery to create a situation of extreme overproduction once wheat or cotton was not needed to win the war. Moreover, these farmers were now burdened with the debt of their new machines.

Now, this particular issue was less prominent in cotton than in wheat because the extremely cheap labor of the sharecroppers meant that mechanization was less necessary. However, the overall state of the farm economy is what led people such as Henry Wallace to push for a broad-based agricultural reform bill that would limit the amount of crops produced by the fecund farms of America, while having the government set price floors and pay farmers not to produce. Republicans had long roundly rejected such a government intervention in the market, but when Franklin Delano Roosevelt became president in 1933, he named Wallace to be Secretary of Agriculture and the Agricultural Adjustment Act was a top priority.

When AAA was passed, the idea was that in the South, landlords would move some of the money they received to reduce the cotton crop to the sharecroppers. But there was no mechanism to make them do that and by and large they did not. What they did instead was to evict thousands of sharecroppers from the land and force them to find their way with nothing. The cotton planters now invested heavily in machines and mechanized the process, vastly decreasing their labor needs and increasingly their efficiency and profits.

Now, we can argue that sharecropping was horrible and exploitative while also arguing that this draconian way to end the system was also horrible and exploitative. In truth, the Black side of sharecropping was already in decline because of the Great Migration. Black rural workers lives were so horrible that many fled north starting in World War I for jobs in the factories and even though they faced enormous levels of racism in the North too, life was still better than in the South. That process had continued into the 1920s. There was less migration during this period from white sharecroppers, many of whom were committed to farming as a lifestyle and wanted to earn enough money to buy their own land. The idea of moving to the city was anathema to them.

So when AAA happened, this created a crisis among rural farm labor with a response that largely depended upon race. For white sharecroppers, they often tried to find new land to work. This is the story of the Joads in The Grapes of Wrath. The story of the Okies gets caught up in the Dust Bowl, but that was actually a relatively small number of people and mostly not sharecroppers. The site of the Dust Bowl on the western Plains was not sharecropping cotton country, but wheat production created before and during World War I. Those were usually landowners who found themselves blown out, baked out, and burned out by the weather. And yeah, some of them went to California. But by far the greater number were sharecroppers thrown off their land during AAA from Oklahoma, Arkansas, Tennessee, and other states. These are the people who gathered their belongings in the jalopies and went to work in the California farms, often to great disappointment. Others ended up buying extremely marginal lands, such as deforested lands in the Pacific Northwest, and tried to make a go of it there.

As for Black sharecroppers, many of them left too. The Great Migration would continue until well after World War II. But having fewer opportunities, others decided to fight. This led to the Southern Tenant Farmers Union. That formed in 1934 in Arkansas. It was biracial, but mostly it was Black croppers. A socialist sharecropper living in the town of Tyronza named Harry Mitchell and a gas station owner named Clay East saw that the owners were not sharing their Agricultural Adjustment Act payments with the sharecroppers and they began organizing their neighbors into what became the STFU. They began to strike in 1935 and soon spread to Texas, Oklahoma, Missouri, and other states.

In Arkansas, it forced politicians to create the Governor’s Commission on Farm Tenancy. Oklahoma passed the Landlord and Tenant Relationship Act in 1937 to encourage long-term residency on the land and promote the government as a mediator of the problems of the sharecropped farm, but conservative outrage led to its repeal in 1939. The STFU joined the Congress of Industrial Organizations’ agricultural union, the United Cannery, Agricultural, Packing, and Allied Workers of America (UCAPAWA) in 1937 but withdrew a year later, worried that UCAPAWA’s communist leadership was looking to take over the STFU. UCAPAWA president Donald Henderson saw the STFU as a utopian vanguard of rural revolution rather than a real union and attempted to overwhelm its leadership with paperwork so he could take it over. When the STFU leadership withdrew, it led to UCAPAWA ending its attempts to organize in the fields, focusing on the canneries, where the CIO (and the CP) was always more comfortable. The break with UCAPAWA severely hurt the STFU’s ability to function, especially as several of its leading organizers were CP and stayed with the union. Two-thirds of its locals collapsed.

As the STFU and landowners battled each other with increasing intensity, the situation finally received some attention from the government. This led to the Resettlement Administration (RA), intended to help sharecroppers find better lives. But the funding for the RA always remained small and the solutions it developed long-term rather than immediate. The government also created the Farm Security Administration (FSA), to provide low-cost loans to poor farmers who wanted to buy their own land but this was not a realistic option for the vast majority of STFU members. The 11,000 farmers around the nation it helped in 1939 was a nice start, but far too small to deal with the scale of the problem. Ultimately, the government did little to alleviate the problems AAA had spawned for sharecroppers.

The STFU declined by the early 1940s. Mitchell continued leading it, called the National Farm Labor Union after 1945, for the rest of his life, but it was only a shadow organization except for some success organizing the California cotton fields in the 40s. Because of the mechanization and industrialization of farming, most of the cotton labor force disappeared from the fields not long after World War II. The same happened for many other crops. The exception to this history of agricultural labor is Latino farmworkers, laboring in exploitative conditions not dissimilar to that of the early 20th century American South. On these farms, usually in more difficult to mechanize fruits and vegetables, the fight continues.

This is the 482nd post in this series. Previous posts are archived here.