Erik Visits an American Grave, Part 1,060

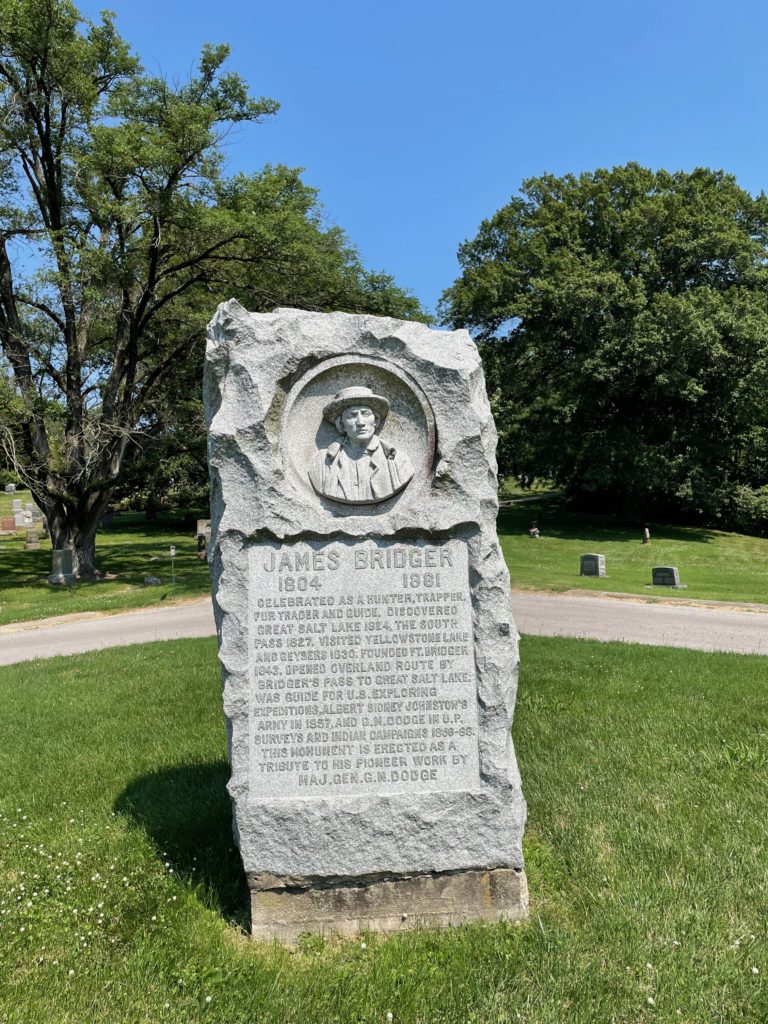

This is the grave of Jim Bridger.

Born in 1804 in Richmond, Virginia, Bridger grew up among the mobile working class of the period. His father ran an inn, but soon got the bug to move West. The family ended up in St. Louis. By 1817, both of his parents had died. Bridger had not learned how to read. In fact, he would never learn to read. He had no money. He had nothing except for being apprenticed to a blacksmith. He hated it and wanted something else. So in 1822, there was an advertisement in a St. Louis newspaper looking for men to join a fur trapping expedition up the Missouri River led by William Henry Ashley. He loved it. It is worth noting something here: fur trapping is one of the most disgusting jobs of all-time, largely because to be good at it, you had to cover yourself in beaver smell. These were very gross men. But that wasn’t going to stop Bridger, not to mention Jedidiah Smith and the other future fur trappers who joined Ashley’s expedition.

For the next twenty years, Bridger roamed the West, trapping furs and pushing forward American empire. He was one of the first whites to see and report on Yellowstone, the stories of which were not believed when members of the Lewis & Clark Expedition had first visited it and told of the geysers and volcanic and geothermal wonders of the place. He was also among the first whites to visit the Great Salt Lake and other areas around there. It’s important to understand people like Bridger in their proper context. They were agents of empire. They may not have used that term to describe themselves, but that’s what they were. They were the vanguard of American power, doing it for a number of reasons–adventure, a dislike of society, money–but they saw themselves as European conquerors bringing capitalism and civilization to the West.

By the 1840s, the furs were being trapped out. But at the same time, men like Bridger could make a living thanks to the second wave of American empire–settlers–wanting to move to the far west. So in 1843, he and his friend Louis Vazquez founded Fort Bridger in modern Wyoming on the Oregon Trail to serve the new trail for settlers. What Bridger did here was serve as the expert for wagon trains crossing the Plains. He could tell them where water was. He could tell them about the Native peoples they would encounter. He could tell them about the land and the condition of the road. But let’s be clear here–Bridger may have been an “expert” but that didn’t mean he knew what he was talking about. His expertise basically consisted of maybe having once been in a place and maybe knowing slightly more than the people he advised. The West is a big place after all. For example, Bridger has some responsibility for the Donner Party disaster. He knew that route across modern-day Nevada a little bit. He knew water was scarce but he believed there was more water around than there actually was. So he told those people that they could cross and sure there was a 40 mile stretch without water, but you could manage that. Well, the stretch of land without water was 80 miles, which nearly killed the wagon train right there, making them late, and then putting them in the Sierra Nevada range right as winter started. Of course there were many people at fault for that disaster, but Bridger deserves his share.

Bridger was also useful to the U.S. military as it expanded national power into the West. First, he worked for the Army in the 1858 Utah War when near full-fledged violence between the Mormons and the U.S. took place. The next year, the Army hired to lead an expedition to Yellowstone to see what exactly this weird place was about. However, it was so snowy that they never reached it, although they did plenty of exploring outside the park. He worked as a guide as well for various wagon trains, mining operations, and other parts of the expansive American empire. In 1864, with the tribes very unhappy about the growing mining expeditions in Montana, Bridger found an alternative to the Bozeman Trail, which was under frequent attack. The Bridger Trail became a popular route to the Montana gold fields. The next year, Bridger, who was as pro-genocide as any other white man, headed the scouts in the Powder River Expedition, which was intended to stop the Native attacks on the Bozeman Trail. They did not succeed in that, but they did manage in killing a bunch of Arapaho who were not resisting white occupation. Meanwhile, Bridger was married to a Native woman. This was pretty common–just because you were married to a Native woman did not mean you weren’t pro-genocide. In fact, Bridger’s first wife was Flathead. When she died, he married a Shoshone woman and then another after that. He had quite a few children with these women but he outlived all but one.

Meanwhile, as the West was being “won,” Bridger embraced the tall tales, the mythology, all the ridiculousness that people wanted to hear about the region. A process already being mythologized as it took place, Bridger embraced his role as agent of empire by telling people the jokes and stories they wanted to hear.

However, Bridger was not exactly a healthy man. It may not surprise you that life on the frontier wasn’t precisely following 21st century health magazines. A lot of drinking and a lack of fresh food was a bad combination. Bridger had to leave the far West in 1868 because he had a nasty goiter plus growing arthritis. He also was going blind, which was complete by 1875. Naturally, the federal government, an unbelievably cheap and stingy institution in this year, refused to pay him the owed rent on Fort Bridger. So he was not in great shape as an old man. He died in 1881, at the age of 77.

Jim Bridger is buried in Mount Washington Cemetery, Independence, Missouri.

If you would like this series to visit other of these old west fur trapper/agents of empire types, you can donate to cover the required expenses here. Auguste Choteau is in St. Louis and Pierre Louis Vazquez is in Kansas City. Previous posts in this series are archived here.