Erik Visits an American Grave, Part 1,049

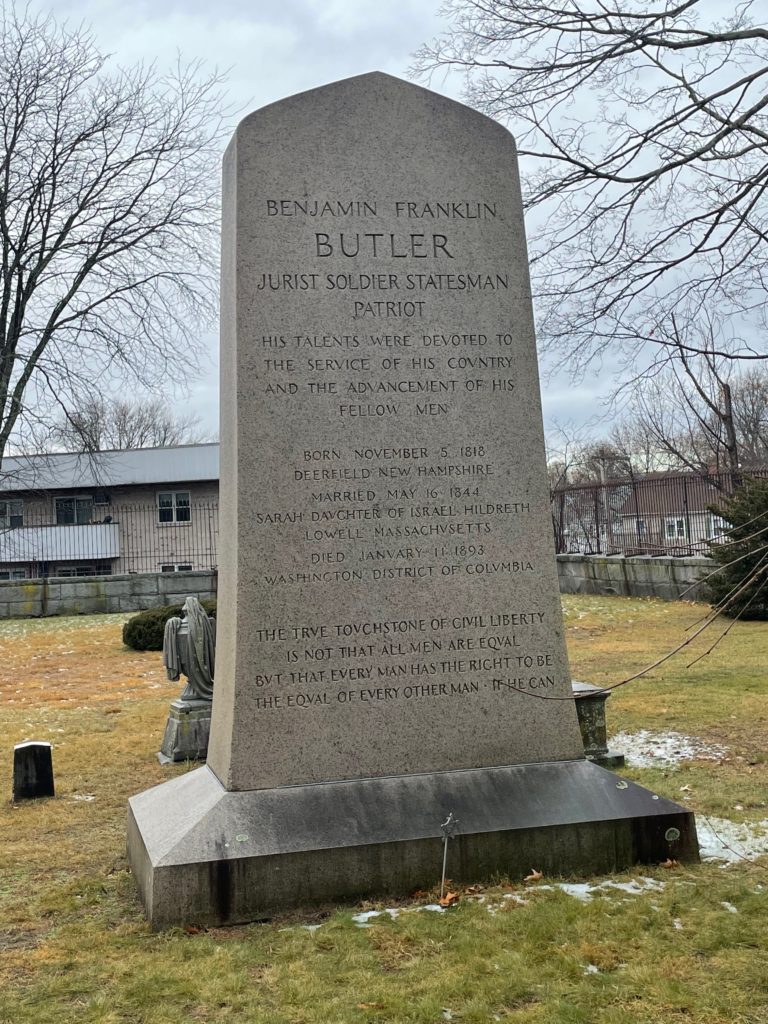

This is the grave of Benjamin Butler.

Born in Deerfield, New Hampshire in 1818, Butler is one of the great weirdos of American history. A man who combined a completely incoherent political stance that led him into every conceivable party and great political leadership in the Civil War that undermined the Confederacy significantly. Butler is a great way to get into the sociopolitical world of the late 19th century.

Butler’s father was a former soldier turned privateer and soldier of fortune who ended up dying of disease in the West Indies. He was fatherless, but the family still had money. Young Butler was seen as very bright and was sent to Philips Exeter for a year when he was only 9, but he got into lots of fights. Plus that family money was going away. His mother moved to Lowell, the experimental factory town, where she ran some of the boarding houses that put up the workers in a way that was supposed to be morally satisfactory. He attended the public schools there where he got into more fights all the time. He ended up being able to go to college, at Colby, because his mother was determined he become a minister. The idea of Butler as a minister is kind of funny. Instead, he wanted to be a soldier and tried to get into West Point, but didn’t get in. So he stayed in Maine, graduated, and got involved in Democratic politics. Early in his political life, this future hero of the North would be a total pro-Slave Power doughface.

Moving back to Massachusetts, Butler became a leading criminal defense lawyer with a reputation for fighting hard for his clients. He soon practiced in both Lowell and Boston and had no shortage of clients. His weird politics already came into play here. He grew up around the textile factories of course. So he would represent workers in fights to lower the hours of work to ten a day. And then he would represent the factory owners if the workers actually went on strike over it. He also became a leading Democrat in the state. Again, he had weird politics already. He was strongly against abolishing slavery but worked with reformers to push Free Soil candidates at the same time he supported Franklin Pierce as president. Part of this is that he was a strong partisan Democrat and that simply mattered more than anything else. But it was also these inchoate contradictions that defined him for his whole life. He was the Democratic nominee for governor in 1859, but lost to the Republican candidate. He also headed a militia made up largely of Irish immigrants. As his own political base was Catholics, he was the top enemy in the state of the Know-Nothings and in fact a Know-Nothing governor broke up his militia for awhile, playing up to the worst tendencies of Massachusetts Protestants about arming Catholics who of course were papists who wanted to overthrow American democracy for the pope, amirite?

In 1860, Butler was a huge supporter of John C. Breckinridge’s southern extremism. But that he would support the most radical Democratic pro-slavery candidate while also being vociferously anti-secession is just typical Butler. He walked out with the southern extremists and was at the Charleston convention of 1860 to coronate Breckenridge. But while there, Butler, who really didn’t want war, threw his support behind a more moderate candidate. That moderate was Jefferson Davis. Then Lincoln won and South Carolina committed treason in defense of slavery. How Butler didn’t see his own contribution to this is hard for me to imagine, but he was genuinely outraged. He immediately went to Washington and told James Buchanan that everyone associated with treason should be arrested, which the weak doughface was not going to do. Butler then met with Jefferson Davis to reason with him, but he was then shocked that the future Confederate president also supported treason.

Given Butler’s political predilections, it makes no obvious sense why he became such a critically transformative individual in the Civil War. He became a commander like lots of these people–he was rich and well-connected. In fact, he really worked it. Butler really wanted to be a general. So he lobbied directly for it. He knew Simon Cameron, Lincoln’s corrupt Secretary of War. So he contacted Cameron and did three things. First, he personally requested that Massachusetts be allowed to add a general to the military. Second, he demanded that he be the general. Third, he contacted his banking friends to make sure that the funding for the militia was dependent on him being the general. Cameron was fine with all of this. So even though Massachusetts governor did not like this at all, Butler became that general.

Butler did not mess around as a general. He was so outraged at the whole idea of treason that he was more aggressive than most other generals. His men ended up arriving in Maryland the day after the infamous Baltimore riot, where pro-slavery thugs killed a bunch of American soldiers. Butler said OK, I’m going to put my men in Annapolis for now. The governor was unhappy. He said that no one would sell supplies to his men. Butler responded that he didn’t need them to sell them. They had guns and would just take them if the people weren’t going to support the troops. He then threatened to arrest any Maryland legislator who didn’t support the Union. Winfield Scott was grateful to have someone not screwing around with any of this treason crap. So the aging general had Butler lead the operation to secure Baltimore for the Union. Butler so outdid his orders though that even though he easily succeeded, Scott couldn’t handle his orders being ignored to this extent and recalled Butler. But that didn’t last long. Butler was too successful at a time when the Union really needed that.

So Butler was sent to take Fort Monroe, the American fort on the mouth of the James River. Taking these coastal forts and cutting off water transportation to the slavers was a key strategy for the Union. He still wasn’t too concerned about acting own his own volition, no matter how mad Scott was at him. So he went ahead and conquered Newport News as well, giving the Union control over southeastern Virginia. Well, this all forced Robert E. Lee to respond, as he feared Butler would move on Richmond. But the problem with Butler is that he was excellent at visualizing how a war should be fought but was very bad at actually fighting a war. There was value for this kind of general, as Butler’s later career would show. But he was strategically not a smart guy, typically being too confident in himself and of course having zero military experience. Lee was able to draw Butler out and then overwhelmed him with superior forces at the Battle of Big Bethel. In fact, he did so poorly, that his permanent commission was nearly rejected by Congress, which voted on these things at the time. But sometimes his confidence could work out. For instance, soon after Big Bethel, uncowed by the criticism of his actions, he led a force that took a couple of key forts on the coast of North Carolina. This led Lincoln to publicly talk of him and then he was sent to Massachusetts to raise more troops.

Well, Butler’s actions at Fort Monroe were pretty mixed from a military perspective. But that’s not why we remember his time here. See, slaves were not just sitting back hoping the North would free them. They were actively pushing for their own war policy. Of the four main groups in the United States as this time–southern whites, free northern Blacks, slaves, and northern whites–the first three knew what the war was about. It was just northern whites trying to pretend it wasn’t about slavery, and not all of those either. So it didn’t take long for runaway slaves to show up at Fort Monroe, forcing Butler to figure out what to do. So he called them “contraband,” following the rules of war that allowed such a thing. Sure they were people but if the South considered them property, well, why not? Butler’s actions around self-freeing slaves were brilliant. One can argue that calling these people “contraband” just went further to dehumanize them. But we had already seen what outright emancipation was going to do–force Lincoln to overrule you and return people to slavery as had happened in Missouri when John C. Fremont tried it. However, Butler was smarter than that. He knew that regardless of his indifference to actual emancipation at this time, he was both following the rules of the war and allowing the southern labor force to become the northern labor force. In other words, instead of growing cotton for the Confederacy, former slaves could dig latrines and cook and do other grunt work for the military, freeing soldiers up for other activities and then helping the Union win the war. Lincoln thought this was brilliant. It was. So there you go. A policy was created. Hilariously, the owners of these slaves who had fled to Butler’s lines tried to invoke the Fugitive Slave Act to get them back. Butler was like, uh, you aren’t part of the United States anymore, Fugitive Slave Act doesn’t apply to you. But god, those southern whites were the most ridiculous people.

After his time in Virginia, Butler was sent to capture Ship Island off of Mississippi in late 1861. Then he led the force to capture New Orleans in 1862. It wasn’t that hard to take due to its extreme vulnerability based on location. Plus this put the Union in charge of the mouth of the Mississippi River, a hugely important military victory. New Orleans was a secessionist hotbed. Butler had no patience with this. Not at all. He found New Orleans completely disgusting. This is because New Orleans was completely disgusting. To be fair, all cities at this time were disgusting. But New Orleans was also a disgusting swamp. Yellow fever ran rampant in the city. So the first thing he did was try and clean up the city to make it livable. That included getting rid of trash and dead animals and sewage. No one knew what caused yellow fever in 1862, but that wasn’t going to stop Butler’s cleanliness campaign. It actually worked too, as a much cleaner city led to far fewer deaths. Butler had some other trash to clean up too: Confederates. The elite of New Orleans were furious to be under control of a damned Yankee, not to mention a slave-freeing one who didn’t put up with any shit. So he simply responded in kind. This is where his nickname “The Beast” came about. The South was predicated on gender norms that allowed men to be as violent as possible but women, especially rich white women, were these gentle creatures above political engagement who deserved chivalric respect. Let’s just say that Butler didn’t exactly see it this way. These women could often be the most aggressive toward the Union soldiers, shouting out them, insulting them, spitting on them, etc. So Butler issued General Order No. 28 which said that any woman not showing respect to a U.S. officer would be treated as a prostitute and arrested. This was a huge outrage to southern elite ideology. Butler did not care. It worked too. The women backed way off. Butler became hated throughout the South.

Another part of his ruling of New Orleans was related to his earlier actions on seeing slaves as contraband. The Confiscation Act of 1862, which generated from his actions at Fort Monroe, legalized the taking of Confederate property for the Union cause. Butler considered how else he might use this. So he started seizing any cotton he could find. But he gave the residents of the city a chance to not have their cotton seized. He had his soldiers go around and get them to sign a statement of loyalty. Many did, out of convenience as much as anything. But about 4,000 didn’t. So Butler just took anything of value that the Army could use from them. He also took control of newspapers. When one editor approached him about disagreeing with the U.S., Butler responded, “I am the military governor of this state — the supreme power — you cannot disregard my order, Sir. By God, he that sins against me, sins against the Holy Ghost.” And he was serious. The same editor used the death of his father in the Confederate Army to write an obituary that praised the Confederate cause. So Butler threw him in prison for three months. He had clergymen arrested for refusing to pray for Lincoln. In short, Butler was pretty harsh, but there was a simple solution to all of this from his perspective–don’t commit treason in defense of slavery. Butler executed a guy who tore down an American flag. He also threatened to execute his old friend Jefferson Davis if he caught him. Don’t think this was bluster. It was not. He probably wouldn’t have even run it by his superiors first.

It should however be said that Butler was far from a perfect person. That included being a rabid anti-Semite. New Orleans had a large Jewish population, not surprisingly given its role as a commercial center. Butler seethed against the city’s Jews, considering them not only traitors to the nation but also to Christ. Ugh. Also, Butler’s commitment to Black rights really was never about anything more than expediency until after the war. So when slaves fled to New Orleans, Butler was overwhelmed. What was he supposed to do with thousands of women and children especially? So he ordered them out of the city and sometimes even returned them to their masters. As I have stated, consistency was not exactly his thing. On the other hand, Butler formed the first all-Black regiment in the Army before this was even really allowed by the military. The 1st Louisiana Native Guard performed quite well at the Siege of Port Hudson and Butler was proud of them. Finally Butler was recalled due to his radical rule of New Orleans late in 1862.

Butler was not a good general in battle, it’s worth noting. In battle, he was completely unskilled and was kicked out of the army after he failed at the Battle of Fort Fisher in 1864. Grant really wanted to get rid of him before this, as the great general really hated the entire idea of political generals. Given that most had proven completely incompetent, Grant mostly had his way but Butler was powerful enough that he really had to show his incompetence to get kicked out. Butler was also totally corrupt in all his dealings with New Orleans. He and his brother definitely profited off this through the sketchy deals becoming the norm as the nation moved toward the Gilded Age. Still, Butler was powerful enough to skate through it all. However, it’s very much worth noting that you know what northern mills did not lack for cotton supplies during the war? The ones Butler owned in Lowell. That confiscated cotton? He was winning the contracts through prearranged auctions. On the other hand, he also recommended that Andrew Johnson prosecute Robert E. Lee for treason and would have hanged him personally if he could.

By this time though, Butler was a deeply committed man for Black rights. He was elected to Congress back home in Massachusetts in 1867. Now associated with the Radicals, he led the fight to impeach Andrew Johnson. He was one of the managers of the trial of Johnson, though many said he didn’t do a very good job of this. This commitment to a vigorous Reconstruction continued into the Grant years. He helped author both the Ku Klux Klan Act of 1871 and the Civil Rights Act of 1875.

I do not doubt that Butler’s commitment to Black rights was real in the 1870s. But the thing about Butler is that he had a greater commitment to himself winning office. To make that happen, there was no principle he couldn’t break. In the most partisan time in American history, well at least before the present, Butler would do the unthinkable–switch back and forth between parties based on his own advantage at the time. Now, I want to be fair here. Butler was a complicated man and the Republican Party had really turned its back on helping anyone but the nation’s new financial elites by the 1880s. Of course he was also a financial elite and also personally corrupt. Again, the whole consistency thing. In any case, he did manage to win the governorship of Massachusetts in 1883, serving a one year term as a reformer, appointing both white women and Black men to public office and cleaning up some really bad corruption he didn’t like. He really, really, really wanted to be president. But the conservatives in Massachusetts had come to hate him. So he didn’t win his reelection bid in 1883. He was furious and now figured the Republican Party was beyond the point of no return. He started aligning with reformers, especially the Greenback Party. Now I don’t think Butler had really expressed reformist ideas about paper currency before, but what did consistency matter for him?

When he ran for Greenback Party president, Republicans saw an opportunity. They were running James Blaine and of course did not want Grover Cleveland to defeat him. Then, as now, third parties were pretty useless and just opened the door for one of the other two parties to divide and conquer. That was certainly the Republican goal and it seems that the Blaine campaign paid Butler $25,000 to help him run in what was an open case of bribery. Butler was not above the corruption of the day, no question. But the Greenbackers never really had that much support. The growing economic discontent of average white people needed a little more time to gestate, as it would with the Populists in the next decade. So Butler only got 175,000 votes and that was not enough to throw the election to Blaine.

After his Greenbacker loss, Butler finally stopped running for things and went into a general retirement from elected office. He wrote a memoir, published in 1892. He died the following year, in 1893, at the age of 74. It was a bronchial infection of some sort, but he was still functional until the end. Literally, he argued a case before the Supreme Court the day before he died. Guess he probably should have rested instead.

Benjamin Butler is buried in Hildreth Family Cemetery, Lowell, Massachusetts.

If you would like this series to visit other Civil War figures who interacted with Butler, you can donate to cover the required expenses here. I can’t say they will make as long of posts as this one (Butler is hard to write about succinctly!), but they will be interesting anyway. William Mumford, the dude Butler had killed for tearing down the flag, is in Kansas City (moved there presumably) and Nathaniel Banks, another political general who replaced Butler in New Orleans, is in Waltham, Massachusetts. Previous posts in this series are archived here.