This Day in Labor History: November 11, 1942

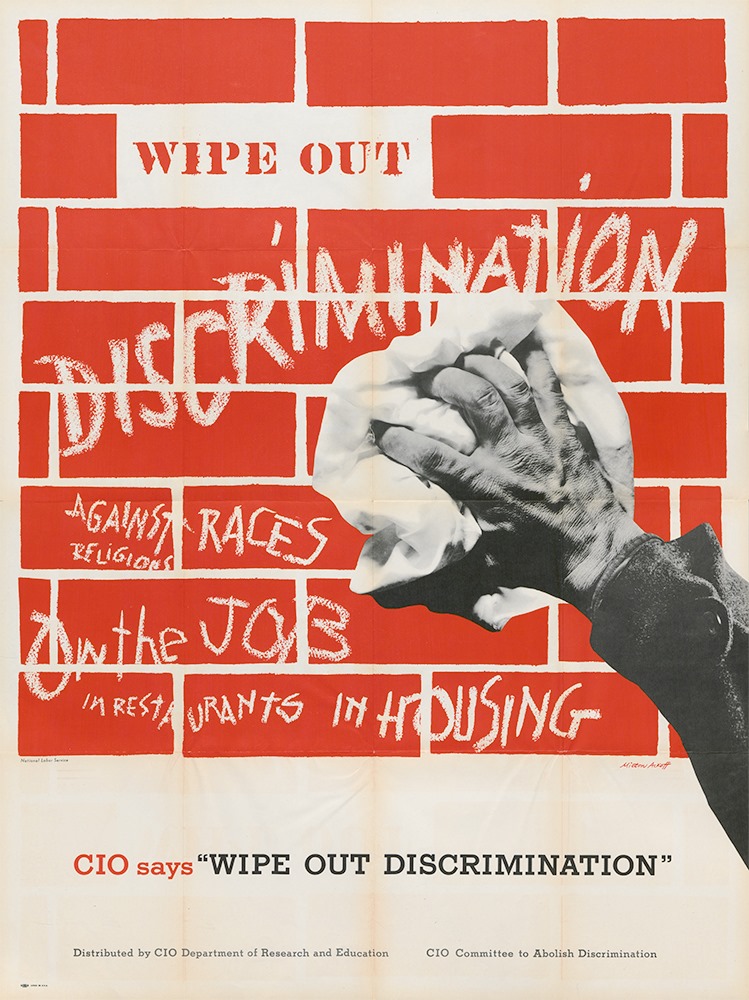

On November 11, 1942, the Congress of Industrial Organizations began its annual convention. One of the key parts of this convention was the creation of the Committee to Abolish Racial Discrimination, an official union effort to combat racial discrimination on the job within the government, at the workplace, and among its own members.

Like every white-led organization in the United States during these years, racism was a serious problem within the CIO. Simply put, white supremacy was central to American ideology. This had gone long to define the labor movement in the United States, with its very long hostility to immigration, especially from Asia, for well over a half-century by the time the CIO formed the CARD. Relationships with Black workers were not much better. Black workers had long been suspicious of organized labor because central to so many unions was keeping an all-white workplace. In fact, this racism was part of the reason the CIO needed to break from the AFL in 1937. The AFL’s reticence to organize on an industrial basis was partly a discomfort with the reality of what the industrial workforce looked like–polyglot, Black, Mexican, women.

So the CIO formed in 1935 and then became its own labor federation in 1937. Some of its unions immediately embraced a real racial democracy. Many of those were communist led. Unquestionably, the white-led organization that did the most to fight racism in the U.S. in these years was the Communist Party. So unions, many of them small, in the CIO had quite egalitarian racial politics. That doesn’t mean all rank and file members felt comfortable with that. Quite the opposite. But official policy matters. A lot. Some of the unions though with a strong commitment to racial equality were much larger, such as the United Packinghouse Workers of America, which finally organized the Jungle in Chicago.

As early as 1936, the CIO had pledged to organize workers regardless of race or color. That was a nice pledge, though maybe was more an aspirational statement than a meaningful one at the time given the CIO’s limited power. But when A. Philip Randolph, always an AFL guy with his Brotherhood of Sleeping Car Porters, threatened his March on Washington that forced FDR to desegregate employers with defense contracts, it gave an increasingly powerful CIO more incentive to do something real. The next year, it created the Committee to Abolish Racial Discrimination. That intended to build on Randolph’s principles and fight against racism in job assignments, promotions, and advancement.

Now, let’s be clear. Some of this was the CIO responding to criticism from civil rights organizations that suggested that the union talked a big game about fighting racism but not doing anything real. This was the critique of the NAACP and Urban League, as well as rank and file Black unionists. It was more than necessary. Despite the talk about Black union rights, for many white workers, their top priority was keeping the workplace lily white. This is what led to such things as the Detroit Hate Strike in 1943, which was hardly the only example of this sort of thing during World War II. The need for rank and file education for white workers on race was of prime importance during these years. It was a hard road. But the United Auto Workers supporting a crack down on its members who struck for an all-white workplace was an important precedent.

George L.P. Weaver, an officer in the United Transport Service Employees Union and a Black man, was the head of CARD. The committee itself was an interracial attempt to confront racism in the union movement. CARD itself did not have a massive impact, but it’s unfair to expect it to have. It basically served as a movement within the CIO to educate workers about the need for racial equality. This itself was a hard enough row to hoe. Roosevelt created the Fair Employment Practices Committee and CARD did a lot of work to build support for this within the CIO membership. Again, there wasn’t that much CARD could really do. The idea that the union movement can recreate the racial and political ideology of their members is overrated. It can help, that’s for sure. But that’s really if rank-and-file members want to listen. Often they do not and resent their unions attempting to address such issues.

After World War II, the communist-led unions, again the leaders for racial equality, were evicted from the CIO in the aftermath of the Taft-Hartley Act, as well as rank-and-file opposition to communists in many unions. This significantly reduced the push within the CIO for racial equality. But at the same time, Black Americans were fighting for civil rights in a new and invigorated way, with both lawsuits and grassroots action forcing racists on the defensive. So this kept anti-racism in the labor movement alive. In 1952, CARD was renamed the Civil Rights Committee. It continued until 1955, when the CIO merged with the AFL. After this, the union movement once again reverted to a general indifference to civil rights, but such movements as the March on Washington for Jobs and Freedom in 1963 would be supported by more civil rights oriented unions such as the UAW and forced the entire federation to greater commitment toward fighting racism on the job.

In the end, CARD itself didn’t accomplish all that much. But it’s still important to note attempts to reorient the labor movement as a movement that also fought racism.

This is the 414th post in this series. Previous posts are archived here.