This Day in Labor History: August 18, 1823

On August 18, 1823, slaves in what is today Guyana rose up in what became known as the Demerara Rebellion. This was brutally suppressed by the English colonialists, but also played a critical role in building abolitionist support in Britain, paving the way for emancipation less than a decade later.

Slaves hated their condition. So in Demerara-Essequibo, which is what the British called this new colony they acquired from the Dutch at the end of the Napoleonic Wars, they started planning to change that. This was a sugar colony like so much of the Caribbean. The British intended to make money off this colony and that meant driving slaves hard. The British abolition of the slave trade in 1807 only made the lives of the slaves still in this colony worse, as the extreme labor shortage that resulted convinced planters to drive them even harder. By 1823, there were probably about 77,000 slaves in the colony, a bit more than half of which were native born and a bit less than half from Africa. There were a couple of thousand free blacks and about the same number of whites.

There wasn’t a particular moment when slaves snapped. They were simply infuriated by their servitude. There were rumors that Parliament had emancipated them and the plantation owners had refused, so that contributed too. In such a slave-heavy society, with relatively few whites, there were layers of slaves, with some having more rights than others. Not surprisingly, the organizing for this came out of slaves with relatively more privileges. A father and son started the planning for resistance. The father was Quamina, who was a deacon at a Protestant church and his son Jack Gladstone was a cooper on a plantation. They started disagreeing though. Quamina wanted a strike that avoided violence. Gladstone was significantly less interested in nonviolence. As the plot grew, they actually took it to the pastor at the Protestant church, John Smith, who did not give the plot away, but rather counseled patience and hope that Parliament would improve their lives. The issue of the churches for Africans was controversial. An 1805 attempt to construct a church led to the Dutch governor kicking the pastor out of the colony. The British were nervous about introducing religion as well but with the rise of the London Missionary Society as a growing power in British life, they reluctantly agreed to establish churches to convert the slaves. The slaves remained enthused by the church, in part because it tended to put pressure on the planters to improve conditions. The planters were…somewhat less enthused. The actions of John Smith would suggest to them why they did not want these meddling missionaries helping out their slaves. Shortly before the rebellion, Smith wrote back to England:

Ever since I have been in the colony, the slaves have been most grievously oppressed. A most immoderate quantity of work has, very generally, been exacted of them, not excepting women far advanced in pregnancy. When sick, they have been commonly neglected, ill treated, or half starved. Their punishments have been frequent and severe. Redress they have so seldom been able to obtain, that many of them have long discontinued to seek it, even when they have been notoriously wronged.

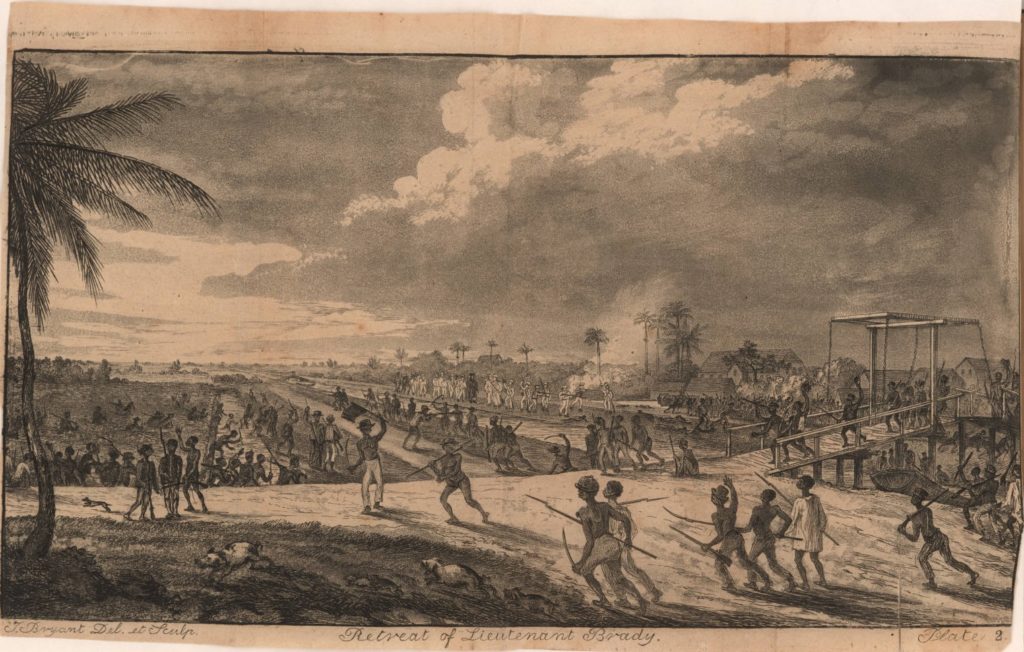

Despite the very real sympathy from the white pastor, Jack Gladstone and his growing number of followers did not want to listen to him, so they rose up on August 18, 1823 at the Plantation Success, where he was a slave. About 13,000 slaves rose up that day, which is actually an incredibly impressive number, though the planners evidently hoped for a complete and total rebellion. They seized the plantation’s firearms and locked up all the white people. This was not a slave rebellion in the sense that it was a desperate attempt to end slavery entirely and return to Africa. Rather, it was more akin to a strike. They took the whites on the plantation as hostages to negotiate for better conditions in the area, not to kill them.

The governor of the colony, John Murray, ordered all the slaves to quit their protest and return to the plantations. When they refused, he declared martial law. The slave revolt continued with quite a bit of discipline and cohesion. Throughout the colony, plantation owners who did not flee to the capital at Georgetown found themselves locked up but not killed–this happened on 37 plantations. But the military was ready to kill all the slaves if need be. On a plantation that actually had the name of “Bachelor’s Adventure,” the militia faced off against thousands of striking slaves. When they refused to disperse, the commander ordered his troops to open fire. Perhaps 200 slaves were massacred that sad day. There were smaller massacres at other plantations.

With this kind of violence, the rebellion was effectively over by late the next day and officially over by August 20. But the governing class of Demerara-Essequibo was furious. Many slaves headed to the swamps and hills to try and survive. Hundreds were captured and brutally murdered. About 200 were decapitated after being shot and their heads put on pikes lining a road. Eventually, the governor decided it made more sense to commute the death sentences and just send the slaves to other colonies. For example, Jack Gladstone was sent to St. Lucia. Quamina managed to remain free for about a month. But he was killed as well and his body chained to the plantation fence for weeks.

Somewhat more remarkably, the colony’s leader also held Smith responsible. Trying a white pastor for a slave rebellion was another thing than massacring slaves entirely. After a trial of a month, he was found guilty and given a sentence of death. He supposedly died of tuberculosis in prison in February 1824. A royal pardon came the next month but was too late. Who knows if he in fact did die of this; certainly the prisons did kill their fair share of people unfortunate to be incarcerated in them.

In the aftermath of this, Smith became a martyr to the abolitionist cause in England. Parliament began to restrict slavery even more, forcing the planters to mostly end whipping (and entirely on women) and allow the free practice of the Christian religion. They nearly revolted and often just refused to allow the laws to be enforced on their lands. But the writing was on the wall and Parliament passed the law to end slavery in 1833, paying off the plantation owners with final emancipation in 1838. Of course, the British would discover many ways of oppressing workers of color in their empire without actual chattel slavery.

This is the 404th post in this series. Previous posts are archived here.