This Day in Labor History: May 16, 1910

On May 16, 1910, the federal government created the U.S. Bureau of Mines to investigate the terrible conditions that killed thousands of miners a year and to attempt to regulate those conditions. It was something, but given the extremely lax atmosphere of regulation in Progressive Era America, it ultimately did very little to protect the workers that kept on dying.

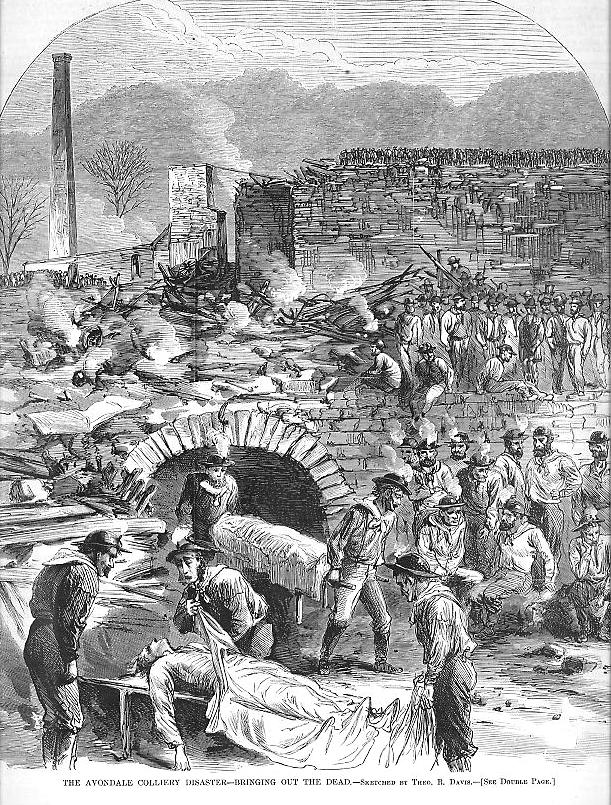

The late 19th and early 20th centuries were horrific for miners, especially in coal. In this series alone, I have covered the 1869 Avondale Colliery Fire in Pennsylvania (110 dead), the 1907 Darr Mine Fire in Pennsylvania (239 dead), the 1907 Monongah Mining Disaster in West Virginia (at least 362 workers but probably closer to 500), and the 1909 Cherry Mine Fire in Illinois (259 dead). This doesn’t even get at the smaller mine disasters that killed 5, 10, 20, 50 workers. It doesn’t get at the murder of strikers and organizers by company thugs. It doesn’t get at the broken strikes and the children dying from malnutrition, and the occupational diseases leading to quite and unmarked deaths. This was a terrible industry.

Meanwhile, those in power rested on the doctrine of free contract, which stated that if workers chose to labor at a job, they accepted the risk involved and thus employers had no obligation to workers, no matter how bad the conditions. The idea that an impoverished coal miners just immigrating from Wales or Poland was equal in power with a coal mine owner or railroad executive was ridiculous on the face of it. But this was the dominant legal doctrine, as the nation saw once again in the infamous Lochner case of 1905.

At the same time, what made the Lochner case important is that states with strong Progressive movements were challenging the uncontrolled dominance of workers by employers. After all, the New York legislature had passed a law limiting the hours of workers in bakeries, leading to the case. This was happening nationally. Theodore Roosevelt intervening to mediate the 1902 anthracite coal strike instead of using the military to bust it was the harbinger of a new day. A limited new day–Progressives were hardly pro-union. But still, workers could have their voices heard in the halls of a power in a way they could not before, or perhaps more accurately be recognized by the powerful that they even had voices.

Mine disaster after mine disaster began to put pressure on the federal government to do something. The disasters did frequently lead to state-level reforms if enough people died. But these reforms were largely ineffective, creating underfunded agencies without enforcement mechanisms that frequently just withered away within a few years. During the decade before 1910, an average of 2,000 people were dying each year in the mines alone, not to mention all the deaths outside the mines from related causes.

The Cleveland administration created the first quasi-regulatory agency for mining in 1896 with the Federal Department of Mines, but it did very little. In 1907, the most deadly year in American mining history, with over 3,000 dead, Roosevelt called for the creation of a U.S. Bureau of Mines to see what could be done. It did not pass immediately, but in 1909, a bill did pass and was signed by William Howard Taft.

The Bureau of Mines was located in the Department of Interior. It also did almost nothing to save workers’ lives. Like the state level agencies, it had no enforcement authority. It could not tell mine owners to do a single thing. It could do research. It could write reports. It could make recommendations. And that is about it. It also served non-safety functions the government wanted to promote, such as the acquisition of helium supplies and disseminating mining research within the U.S. around the world. Not surprisingly, the emphasis of the agency almost immediately shifted away from safety to these more business-oriented programs. That’s what it became known for and no doubt was quite effective at these tasks. Mining safety was part of the agency into the 1970s, but was never a major part of what it did functionally; the 1970s moves reflected the first time in American history that the government actually got serious about protecting miners from death and thus created a new effective agency.

To be fair here, the Bureau of Mines did engage in some valuable research in its early years. Its first head, Joseph Holmes, was committed to finding ways to stop workers from dying, even if mine owners had to adopt his suggestions voluntarily. The Bureau worked on efficient mine rescue operations, developing better equipment for mine rescues, safer explosives, better roof supports, lamps that would not set mines on fire (a major problem), and other safety issues. So long as they didn’t actually have to do anything, plenty of mine owners were interested in having the Bureau’s agents come and give safety demonstrations to workers, for instance.

In the aftermath of the creation of the U.S. Bureau of Mines though…not much changed. The mines did slowly become slightly safer and the death tolls did decline some, but that had much more to do with better technological developments and fewer workers in the mines than it did with any kind of meaningful regulation. The 1917 Speculator Mine Fire in Montana (168 dead) showed that these were still enormous problems. Having the Bureau was better than not having the Bureau, but not by that much.

Ultimately, if the story of the Bureau of Mines should tell labor activists anything, it’s that regulatory agencies without enforcement mechanisms are completely worthless, then and now. Today, our regulatory agencies are far too hamstrung by corporate control, helping to create a new era of indifference to workplace safety, as we have seen in the COVID-19 era.

If you need extra detailed information on the history of the U.S. Bureau of Mines, here’s a thorough essay on it.

This is the 392nd post in this series. Previous posts are archived here.