Racism and Science

There is so much conversation about racism in science and technology today because that very real history is leading to major policy impacts as people of color are volunteering for the COVID vaccine at far lower rates than whites, despite a year of their families being decimated by the virus. Here’s an article from Canada on the issue:

Science is meant to be objective. In order to be trusted, it is to be free of any bias or prejudice and simply rely on experimentation, observation and conclusions.

However, that has not been the case when it comes to race. And centuries of scientific racism have been hard to shake — even to this day, where the effects are still being seen and felt.

Roberta Timothy, a scientist and researcher at the University of Toronto’s Dalla Lana School of Public Health, said that racism can be seen in the response to the current pandemic.

“Black people are disproportionately being impacted by COVID-19,” said Timothy, who is researching the Black experience during the pandemic. “They’re not being prioritized as a population to be supported, to be cared for, et cetera. And that comes from a history of anti-Black racism and a history of looking at how science is racist.”

…

These perceived differences have helped drive centuries of oppression. Concepts like these, which appeared to be rooted in science, were used to rationalize slavery. Painful experimentation was conducted. Segregation was justified.

There are many historical examples. In the 1700s, enslaved men and women were used as guinea pigs to test smallpox vaccines. Between 1845 and 1849, J. Marion Sims, considered the father of gynecology, experimented and operated on Black women with no anesthesia, as it was widely believed that Black people didn’t experience pain the same as white people did.

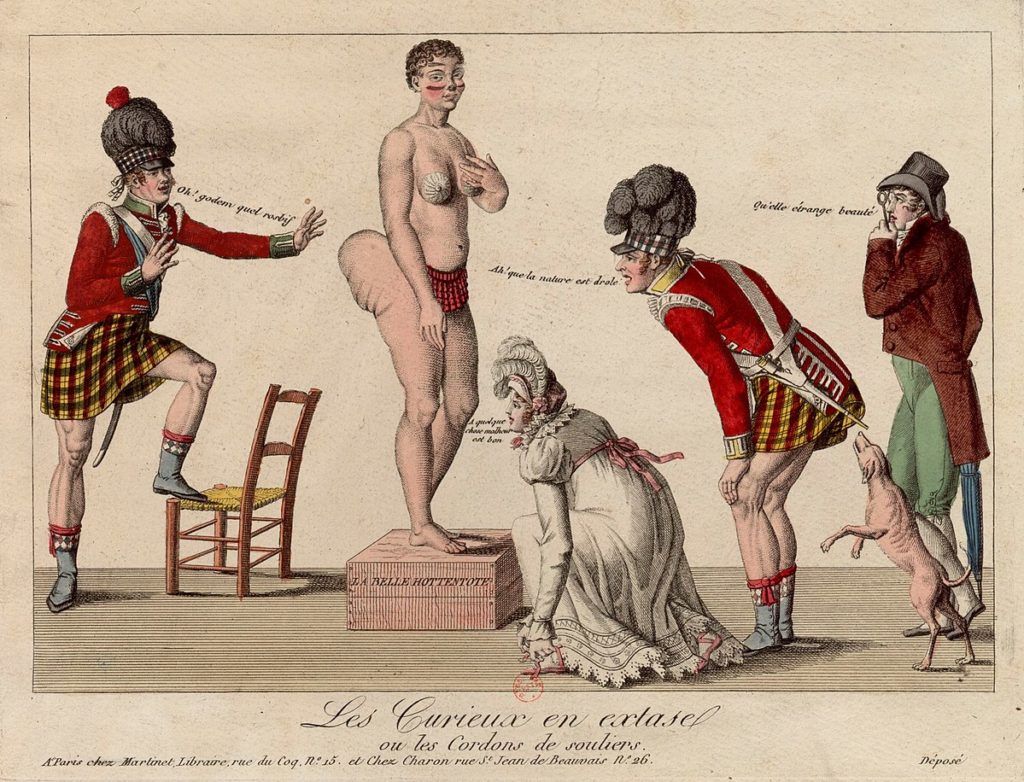

In 1810, Sarah Baartman was taken from her home on South Africa’s Eastern Cape and put on display in London “freak show” carnivals, where people could gawk at her semi-naked body.

Why? Because she, as with many of her Khoikhoi people, had large buttocks not seen before. (This trait, in which there is a high amount of tissue in the buttocks and thighs, is called steatopygia.) Referred to as the “Hottentot Venus,” Baartman died in 1815, at the age of 26, in France.

Here’s the thing: unless the entirety of your scientific question, research planning, and dissemination of your findings is designed to be explicitly anti-racist, there is a very high chance of it building on a racist past to create a racist present. Like everything else in society, scientists, tech designers, and engineers have to reckon with their own legacy of racism in order to fight this. Alas, too often there is resistance to this, as if science is something that is not part and parcel of human society but instead something purer. It is not.