Women’s Suffrage on the Centennial

On the centennial of the Nineteenth Amendment, there’s a lot of interesting writing about its legacy, not to mention awesome grave posts about suffragists.

First, while it’s always a bit tricky to read queerness back into the past (see the lame claims that Lincoln may have had same-sex relationships, which of course it is impossible to know, but these claims simply don’t understand Victorian male culture), it’s also worth noting that many of the suffrage activists are also part of our somewhat lost and obscured lesbian history.

In 1920, the suffragist Molly Dewson sat down to write a letter of congratulations to Maud Wood Park, who had just been chosen as the first president of the League of Women Voters, formed in anticipation of the passage of the 19th Amendment to help millions of women carry out their newfound right as voters.

“Partner and I have been bursting with pride and satisfaction,” she wrote. Dewson didn’t need to specify who “partner” was. Park already knew that Dewson was in a committed relationship with Polly Porter, whom she had met a decade earlier. The couple then settled down at a farm in Massachusetts (where they named their bulls after men they disliked).

Dewson “made every political decision, career decision based on how it would affect her relationship with Polly Porter,” Susan Ware, a historian and the author of “Partner and I” and “Why They Marched: Untold Stories of the Women Who Fought for the Right to Vote,” said in a phone interview.

Dewson was far from the only suffragist who had romantic relationships with women. Many of the women who fought for representation were rebels living nonnormative, queer lives.

Carrie Chapman Catt, a president of the National American Woman Suffrage Association (NAWSA), settled down with Mary Garrett Hay, a prominent suffragist in New York, after the death of Catt’s second husband. Catt asked that she be buried alongside Hay (instead of either of her husbands), which she was, at Woodlawn Cemetery in the Bronx.

And Dr. Anna Howard Shaw, another NAWSA president, had a decades-long relationship with Lucy Anthony, the niece of Susan B. Anthony. Though the elder Anthony was concerned about her niece’s long-term well-being, given more than a decade difference in their ages, she understood the kind of relationship she was in, said Lillian Faderman, a scholar of L.G.B.T.Q. history, who wrote the book “To Believe in Women: What Lesbians Have Done for America — A History.” Shaw “assured Susan that she would take care of Lucy forever,” Faderman said in a phone interview, “and she did indeed do that.”

These are important stories to reclaim.

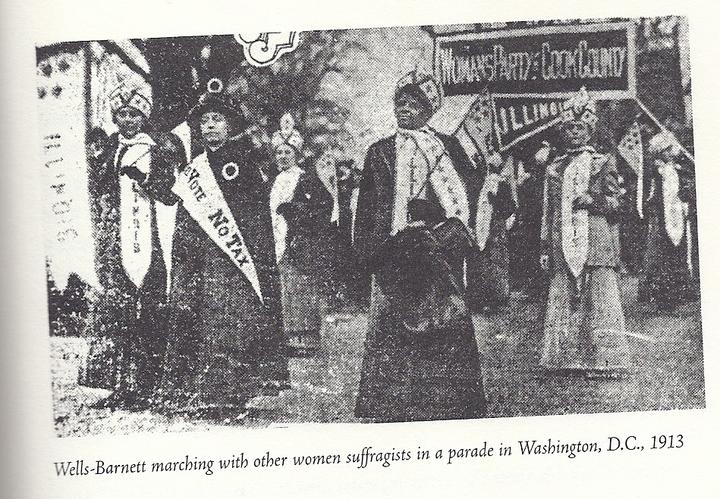

On the other hand, our memory of suffrage is, like so much of our collective memory, even on the liberal left, exceptionally white. Scholars of non-white Americans have been making these points repeatedly as the centennial has arrived. The Nineteenth Amendment did not grant women the universal right to vote. It only granted white women that right.

In other words, after its ratification, states were no longer allowed to keep people from the polls just because they were women. But officials who wanted to stop people from voting had plenty of other tools with which to do so.

States could use poll taxes and other voter suppression tactics — already used across the country to deny voting rights to Black men — to keep Black women from voting. They could, and did, use those same tactics against Latina women. Indigenous women and many Asian American women lacked citizenship in 1920, meaning they couldn’t vote in the first place. All in all, the 19th Amendment was essentially for one group of women and one group only: white women.

That was by design. White suffragists like Elizabeth Cady Stanton may have championed equality for women, but in practice, they often meant women like themselves. And in the drive to get states to ratify the 19th Amendment, white advocates wanted the support of Southern white women — and their husbands and fathers — and were willing to sacrifice Black Americans’ voting rights in order to get it. They were also willing to set aside the rights of Native American and Asian American women, even though they sometimes invited these women to appear at events as a way to build interest in their movement.

Therefore, despite all the celebration around the 19th Amendment,millions of women around the country were still prevented from voting in 1920 because white suffragists bargained against them. The racist laws and practices that kept them from the ballot box would take decades to undo — and, in some cases, persist to this day.

But activism for women’s voting rights did not end in 1920, and the advocacy of women of color like Fannie Lou Hamer and Diane Nash helped lead to perhaps the biggest voting rights victory of all, the Voting Rights Act of 1965. Now, in a time when many Americans are still prevented from voting by ID laws and other suppression tactics, women of color in politics are looking to and building on the legacy of these earlier advocates.

It’s critical to center the stories of people of color here because erasing them both reinforces the white narrative that white suffragists themselves created and also forgets that while the Supreme Court may not care today if white women vote, they very much want to stop Black women from voting, as the Roberts Court has shown again and again.