Here’s Something Not Terrible

To distract us from all the horrible things in the world, here’s a great story on how a Catholic library in Cairo began collecting street-level Islamic religious texts in the 1950s and have compiled an invaluable collection of material that would have otherwise been lost. This is the by the scholar, as Islamic woman herself, involved in digitizing it all.

The IDEO’s rare books collection is currently in the process of being digitized for online open access, in collaboration with France’s national library Bibliothèque nationale de France (BnF). This is where I come in. My work examines the history of the transition between manuscript and print in Arabic in the 19th century; thus, I have plenty of experience using this particular collection. I almost cried the first time I pulled out one of their prayer books from the 1880s. I dropped everything and ran into Jean’s office to show it to him. “That’s crazy” he said, indulging that excitement of finding exactly what you want in a library or an archive. He smiled knowingly at me, then returned to his work. Over time, he began to clue me into the digitization process and asked me, since I was always pulling rare books out of the collection, if I wanted to pick the books IDEO digitized.

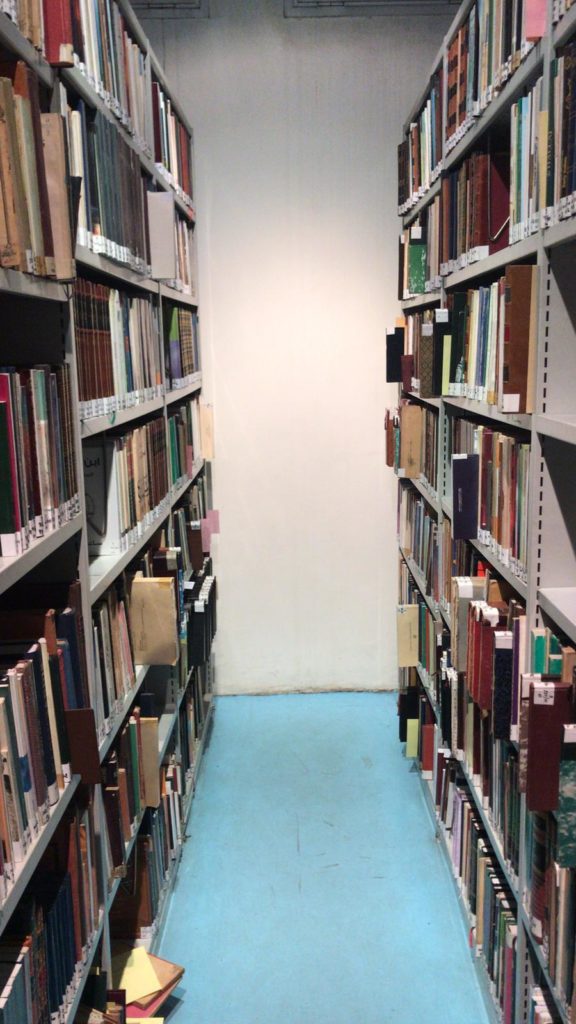

The texture of my visits to the Dominicans changed as soon as I began working on the project. Instead of going to sit in the library itself, I head downstairs to the collections, which are closed stacks. Amir Samir, who is one of the staff members responsible for the stacks, goes over the set-up and his meticulous standards for how I am to behave in the stacks. Finally, he hands me bright yellow cards: these will function as “ghosts,” that I will put in the place of the books I have taken off the shelves to consider for digitization. The cards have a place for the title of the book, their classmark, their inventory number, and the date I removed it from the shelf.

My work begins with the IDEO online catalog itself. I review the catalog’s classifications, which correspond to different subjects. I gravitate towards the subject of tasawwuf.3 I take my yellow cards, which I fill out as I go along, and enter the stacks, retrieving what copies of tasawwuf works I’ve identified from the catalogue. But my eyes find much more. I begin pulling the slim volumes off the shelf based on the binding, which hints that the books are older. I open them, and flip to the front page to confirm.

These prayer books have been rebound by a professional, keeping the original book covers, a thin cardboard-paper hybrid. Jean told me to focus on texts produced before 1950: these are the metrics he and the BnF have decided on. These books are the bulk of what I am recommending for digitization. I bring a stack of ghost cards to slip into the stacks and take the books away with me to enter into the spreadsheet Jean gave me: it functions as a replica of the metadata available in the IDEO catalogue.

…

There’s the ethics of it, too. The books IDEO digitizes will continue to live in Cairo, but they will also go online, for anyone to download. And my profession–the academic study of Islam and the Middle East–will exploit them for personal gain. People who don’t know many Muslims or our cultures will use them. At least when academics came to use them in person they were coming to Egypt; digitization will eliminate that need. What scares me the most, however, is that Muslims will never pray from these devotional texts again. The texts themselves might be reproduced somewhere else but these material objects were created for prayer. And if the prayers aren’t reproduced somewhere else, they will disappear forever. I do not care if an academic ever uses these books but I want other Muslims to know they exist. But then the conversation ends as my friends and I are interrupted by one of the cats in the garden who wants to be held. Talk then veers to whether or not we’re watching a Marvel movie that upcoming Sunday afternoon. We’ll ask Jean if he wants to come, too.

Finding out how historical scholarship happens is really important. It really a matter of someone bothering to collect stuff no one else would have thought worthwhile, maintaining that collection, then someone has to have the resources to organize it, then someone has to find it useful. It’s all kind of magic.