Erik Visits an American Grave, Part 570

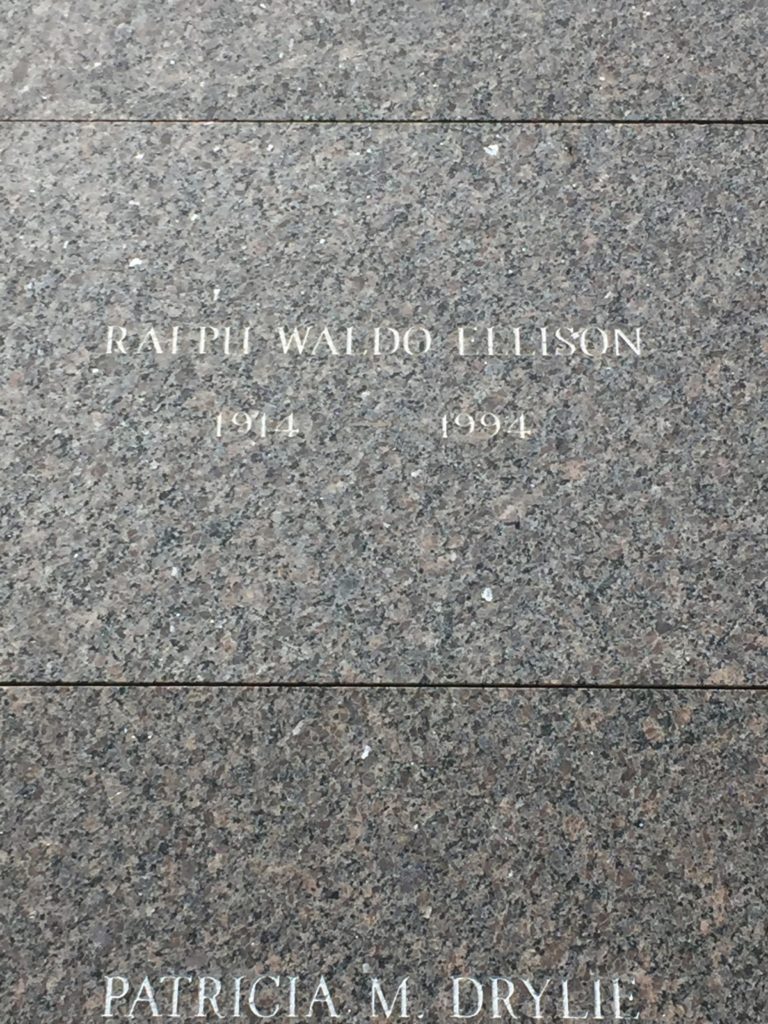

This is the grave of Ralph Ellison.

Born in 1914 in Oklahoma City, Ellison grew up without a father. See, African-Americans worked the most dangerous jobs at a time when all jobs were pretty unsafe. So not surprisingly, Ellison’s dad died on the job in 1916, when a 100 pound block of ice pierced his abdomen on the job. In fact, his father was a foreman for a black construction company so he wasn’t just a laborer, but still. In 1921, Ellison, his mom, and his siblings moved to Gary, Indiana, where they had family. But Ellison’s uncle they were counting on for a hand lost his job and the family, impoverished, returned to Oklahoma, The young Ellison worked a huge variety of jobs as a child and dealt with an unstable family life as his mother married three more times. He also became a musician. This was a critical thing for him. He applied to Booker T. Washington’s famed Tuskegee Institute. The first time he was rejected. But the second, well, the school band needed a trumpet player. So he was admitted. I’d say things worked out.

Ellison spent his time reading and playing music at Tuskegee. He never really fit into the Tuskegee culture and yeah, I’d say that worked out in his favor. He read all the modernist classics while taking a wry eye to his surroundings. After graduation, he moved to New York in 1936, lived in Harlem, came to know Langston Hughes, and also came to know the fertile field of politics that was communism in Depression Era New York. He also met Richard Wright and starting writing book reviews and essays. He got involved with communism but also found the CP totally hypocritical during World War II, when it was far more concerned with defending the Stalinist USSR than issues in the U.S., including racism. Despite its verbalization of anti-racist politics, Ellison found them as hypocritical as other whites.

And that started what I would argue is the greatest novel in American history, Invisible Man. This took a long time to write. He was not drafted in World War II and enlisted in the Merchant Marine late in the war, but never say any action. He relied on his wife, the writer Fanny McDonnell, to support him while he wrote his great novel. Finally, in 1952, Invisible Man was published. It’s hard for me to express how much I love this book. The first two parts are utterly brilliant. The first, at Tuskegee, is such a cold view of both the hypocrisy of Tuskegee and an understanding of why it was hypocritical. Our uptight, forward-thinking, do-gooder narrative there runs up against the whiteness of Booker T. Washington’s rich funders who were perfectly clueless about southern life until they weren’t. I am not a literary critic at all so I imagine there is some literature about this, but I always have found it odd that The Founder is so obviously Washington and yet Washington is referenced by name later in the book. Maybe he was covering his bases, I don’t know.

As those of you who have read Invisible Man know, which I assume is all of you because how have you not read the best novel ever published in the United States unless you are reading stupid fantasy stuff, our narrator gets kicked out of Tuskegee and is given letters of introduction to rich white New Yorkers, all of which tell them to never hire this wild boy who exposed a white man to the real black South. So, by accident, the narrator ends up as a communist. This is such wonderful writing. It places the CP at violent odds with the Garveyites and also the narrator at odds with the white CP members who claim to care about race but actually don’t. It’s the ultimate literary attack on Class Not Race leftists, showing their ignorance and racism and pointlessness. And as a novelist reflecting reality, there is certainly no positive ending here. While I actually don’t care for how Ellison concludes the book (as I don’t care for the ending of the other competitor for the greatest American novel, The Adventures of Huckleberry Finn, which also tries to handle the nation’s complex racial issues), there is no question of his laser-like ability to spot the contradictions of American ideals, the realities of racism, and the reality of life for African-Americans.

Invisible Man was released to enormous acclaim. Ellison won the National Book Award in 1953. Alas, there would be no second novel. Ellison published a lot of essays. In 1967, his house burned down and Ellison claimed the fire burned 300 pages of his next novel, which I don’t doubt is true, but it had already been 15 years so who knows if it would have ever been published. Supposedly, Ellison wrote 2,000 pages of a new novel but didn’t like it. And I respect that. Writing is really hard and is basically a horrible, awful, no good process that mostly leads to self-hatred. Do I wish Ellison had written another book in the last 42 years of life? Yes. But I also understand why he didn’t. And it’s not like he was some slacker. He continued to write essays, many of which on jazz, that are really valuable. After his death, a version of that novel, Juneteenth, was published. I haven’t read it because I feel I shouldn’t. Maybe I will at some point. Ellison died in 1994.

Ralph Ellison is buried in Trinity Church Cemetery, Manhattan, New York.

If you would like this series to visit other African-American writers, you can donate to cover the required expenses here. Zora Neale Hurston is in Fort Pierce, Florida and Octavia Butler is in Los Angeles. Previous posts in this series are archived here.