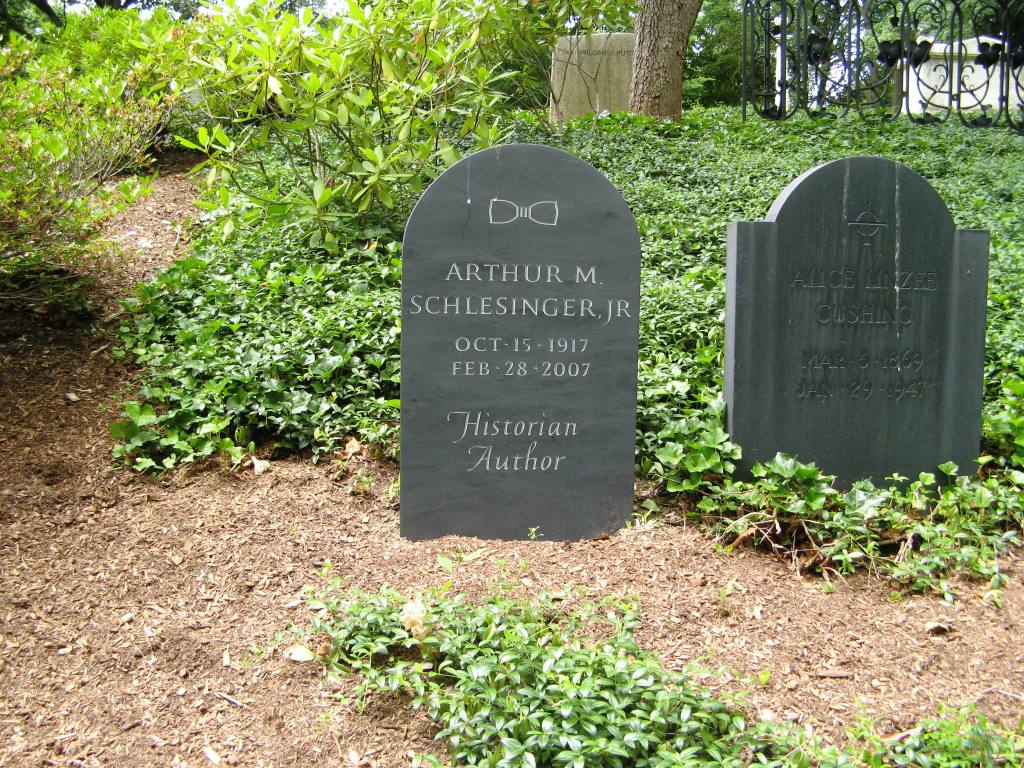

Erik Visits an American Grave, Part 227

This is the grave of Arthur Schlesinger, Jr.

Born in Columbus, Ohio in 1917 to legendary early social historian Arthur Schlesinger Sr and Elizabeth Bancroft Schlesinger, a relative of George Bancroft, it seems almost inevitable that young Arthur would go into the family business. He never earned a PhD but after graduating from Harvard in 1938 and spending a year at Cambridge, he was given a Junior Fellowship in the Harvard Society of Fellows, which was an academic appointment that actually wouldn’t let someone get a PhD. It was only a 3 year deal, but he never went back to school. Instead, after serving in World War II, first in the Office of War Information and then in the OSS, he would become a professor at Harvard.

Schlesinger became nationally famous immediately after the war, when he published The Age of Jackson. Now, no one takes this book seriously now. But they did for a very long time. In fact, it was assigned to me in a course on “Jacksonian America” in college in the early 1990s. The fact that the course was even named that came in part from Schlesinger’s influence. No one would title a course that these days. Today, it mostly gets pilloried for not even mentioning Jackson’s Indian Removal policies. How is that even possible? Well, it was bad. But it really isn’t that surprising when placed in context of how New Deal liberals viewed the world. Having explored quite a bit of 1930s and 1940s primary source material over the years, although nothing from Schlesinger, one thing that really strikes me is how obsessed these people were with narratives of American progress drawn from Frederick Jackson Turner. Even if they don’t mention Turner by name, a lot of New Deal liberals and lefties talked in terms of the Frontier Thesis to describe the nation past, present, and, they hoped, future. And while people such as John Collier did try to include reforms on the reservations as part of the New Deal, there really wasn’t a place for Native Americans in the New Deal view of the world. Now, I don’t know how Schlesinger justified excluding Native American issues from his book on Jackson. It seems inexplicable. But it also very much reflected the views of that time. I mean, how did John Steinbeck exclude Mexicans and Filipinos from The Grapes of Wrath and In Dubious Battle? That is no less imaginable to me. But in both cases, American liberalism and the nation’s democratic potential and the struggles and triumphs and failures of of the working class was a story of white people. None of this is excusing Schlesinger on this front. But he wasn’t the only sinner. Moreover, this story of democratic striving and the breaking down of elite privilege in the early 19th century appealed very strongly to New Dealers a century later, which is why the book won the Pulitzer Prize.

Schlesinger became involved in Democratic Party politics at an early age. Initially, he was a bit of a lefty but moved toward an anti-communist liberalism pretty fast. Being a rich Harvard elite from the time his dad moved there from Ohio State, he grew up around privilege and ran in those circles, knowing everyone. He co-founded Americans for Democratic Action in 1947 with Eleanor Roosevelt, Hubert Humphrey, John Kenneth Galbraith, and Reinhold Niebuhr. He became a big booster of Adlai Stevenson and was his chief speechwriter for some time. He also became friends with the Kennedys, especially after JFK intervened in 1954. when the Boston Post was going to run a bunch of stories exposing supposed Harvard commies, including Schlesinger. The historian repaid his friend by jumping to him from Stevenson for the 1960 nomination.

After Kennedy was elected, Schlesinger became an important advisor. He resigned from Harvard and was appointed Special Assistant to the President in 1961. Here he worked mostly on foreign policy issues and, like much of Cold War foreign policy, it gets really depressing when you wade into the details. To his credit, he opposed the Bay of Pigs as a very bad idea. But he said instead the way to deal with Castro was to bait him into invading Haiti or another country, turning the world’s attention to his evil, and then the U.S. could invade and destroy the Cuban Revolution. This was indicative of Schlesinger’s foreign policy. He wasn’t as hawkish as Robert McNamara, but he would always look for ways to fight leftists. Thomas Field’s From Development to Dictatorship, a book about Cold War Bolivia and American foreign policy, goes into Schlesinger’s actions there in great detail. After Victor Paz took power in 1952, a lot of cold warriors thought he would turn Bolivia to the left. But by 1961, the Kennedy administration saw him as a key ally in the Alliance for Progress. There was a lot of leftist agitation in Bolivia at this time, especially from the miners. So basically Schlesinger went to Bolivia, warned Paz that he needed to crack down on the left, and opened the door for murderous repression of the miners. Schlesinger reported back to Kennedy that Bolivia was probably going to become the next Cuba and that Paz could not be trusted. So the administration needed to fund the Bolivian military to become the bulwark against communism.

Now, what in the hell is a historian of 19th century America doing gallivanting around Latin America setting policy and urging the killing of communists? But in the land of Camelot, the best and brightest bumbled their way around the world doing all sorts of horrible things, including paving the way for the Vietnam War.

Lyndon Johnson had no use for someone like Schlesinger. He resigned in 1964 and wrote A Thousand Days. I haven’t read it, nor do I have any desire to read it. He took a job at the CUNY Graduate Center and taught there from 1966-94. But of course he was still milling about in politics. He worked for RFK’s 1968 campaign before the assassination. He hated Nixon and Nixon returned the hate. Schlesinger was on the Enemies List. Then Nixon bought a house next to Schlesinger after Watergate.

He became a cranky old white liberal as he aged. By the 1980s, the world that would allow The Age of Jackson to be written without mentioning Indian Removal was fading. Multiculturalism was replacing that white populist democratic optimism of the New Deal generation. And Schlesinger hated all of it. He had no use for a society centered on identity politics or on seriously grappling with racism and sexism. Having bought in fully to the “melting pot” he wrote The Disuniting of America in 1991 to decry threats to assimilation. Using words that would provide succor to racist pseudo-intellectuals everywhere, Schlesinger wrote of multiculturalists, their “mood is one of divesting Americans of their sinful European inheritance and seeking redemptive infusions from non-Western cultures.” In other words, stop making me think about whiteness or that Andrew Jackson did horrific genocidal things to Native Americans.

To be fair, Schlesinger hated Bill Clinton’s DLC centrism and opposed the Iraq War. He died in 2007 when his heart stopped in a Manhattan restaurant while was eating with his family. He was 89. Not a bad way to go.

Arthur Schlesinger Jr’s bowtie grave is in Mount Auburn Cemetery, Cambridge, Massachusetts.

If you would like this series to visit more historians, Kennedy administration officials, or New Dealers who pretended like Native Americans didn’t exist, you can help cover the required expenses here. Previous posts in this series are archived here.