Worst American Birthdays, vol. 36

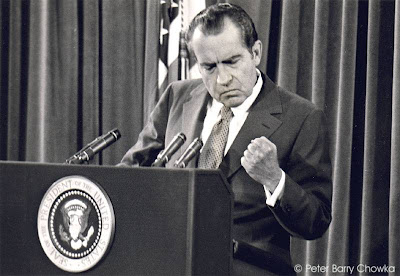

Richard Milhous Nixon was born 95 years ago today.

After California’s gubernatorial election in 1962, one observer wrote that Richard Nixon had been sent to “that small place in history that belongs to natural disasters that did not happen.” The disaster, as it happened, was merely postponed by six years. When it came, ordinary language nearly failed to describe it.

As nearly everyone who studies Nixon’s life and works has observed, the man was a stew of psychopathology. As both candidate and as president, Nixon made a virtue of secrecy, which he viewed as the key to strength. Rather than soliciting enthusiasm from Congress and the public for his policies, Nixon’s White House preferred to act without public scrutiny and debate. Among other things, this disposition enabled him to continue a war in Vietnam that he knew could not be won but which, in public, he insisted could be concluded with “honor” as well as victory. By the end, more than 20,000 Americans died so that Richard Nixon would not have to suffer the indignity of appearing weak. In every other venture, he concealed whatever he could — including the invasion of Cambodia — for as long as he could, bypassing government bureaucracies and actively deceiving nearly everyone outside his inner circle. Nixon ran foreign policy from the White House with very little input from the Defense or State Departments, both of whose secretaries, Melvin Laird and William Rogers, Nixon’s goons had wired for sound. Like most of the late 20th century’s behemoths of the right, Nixon was particularly suspicious of the State Department, which he believed to be staffed with Ivy League liberals who would “sabotage us from within [or] sit back on their well-paid asses and wait for the next election to bring back their old bosses.”

When the “next election” actually cycled around in 1972, Nixon’s squad of burglars and saboteurs — backed by the full faith and credit of Tricky Dick himself — set in motion the events that would eventually leave him wandering the White House, soaked with drink and pondering suicide, by the summer of 1974.

When Nixon’s brain exploded nearly twenty years later, Hunter Thompson offered him a fitting eulogy.

If the right people had been in charge of Nixon’s funeral, his casket would have been launched into one of those open-sewage canals that empty into the ocean just south of Los Angeles. He was a swine of a man and a jabbering dupe of a president. Nixon was so crooked that he needed servants to help him screw his pants on every morning.

If hell exists, Richard Nixon is surely there now, bubbling on a spit like an unwanted convenience store hot dog.