“Manson was just that—A convenient, spontaneously-appearing boogeyman.” A discussion with historian Jeffrey Melnick about his book, “Charles Manson’s Creepy Crawl: The Many Lives of America’s Most Infamous Family”

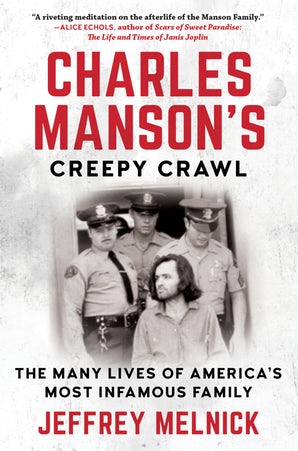

Fifty years after the Summer of ’69 and nearly two years after Charles Manson’s death, the Manson family murders remain the most notorious crime spree in American history, with psychic reverberations that continue to haunt the culture like a spectral hippie phantom. How it is that a marginal drifter and devoted white supremacist came to command a small army of acid-drenched counterculture dropouts and compel them to wicked deeds is the stuff of noir-ish nightmares, a contemporary Grimm’s fairy tale that terrifies and titillates at a primal level. University of Massachusetts history professor Jeffery Melnick’s outstanding recent survey of the Manson murders and their long-spiraling ramifications Charles Manson’s Creepy Crawl—initially published in 2018 with a paperback edition recently issued—is filled with fresh insights and perspectives on how the incident impacted our society far beyond two crazed nights in August of 1969. I recently spoke to Melnick about Manson’s impact on the death of Utopian idealism, its role in the rise of the American right and the many ways in which the saga has been misconstrued and manipulated through the decades, including Quentin Tarantino’s recent hit film Once Upon A Time… In Hollywood.

EN: Given the recent success of Once Upon In A Time… In Hollywood, I was particularly interested in the direct line you draw between the Manson murders and the famous horror and vigilante films of the 1970s ranging from Wes Craven’s Last House On The Left to Tobe Hooper’s The Texas Chainsaw Massacre to Sam Peckinpah’s Straw Dogs. The Manson murders are often referenced as the death of the hippie dream as it were, but less often thought of as a harbinger of the cultural and political shifts to the right which would characterize much of the ensuing forty years. Do you see Manson as a sort of functionary of the reassertion of conservative values generally, and do you think this might have been somewhat mitigated had he not become such a sensational boogeyman?

JM: Can I answer in two slightly eccentric ways? First by talking about the television show Aquarius and then by talking about Tom O’Neill’s heartbreakingly misguided recent book Chaos? Here’s the thing about Aquarius: it is a batshit crazy mess. But it has this one very admirable quality about it, which is that it plots Manson into a California political/cultural history that stretches back into the late 1950s and makes clear that the forces of reaction were plotting their takeover of the state—and the nation—way back then. I mean we know this from the scholarship on California—it’s all there in work by Mike Davis and Eric Avila, whose wonderful book Popular Culture in the Age of White Flight uses case studies about the building of Dodger stadium, freeways, film noir, and Disneyland, to explore suburbanization and the rise of the conservative movement in California. Those guys—like me—are focused on Southern California, but we also have loads of great work on how the Free Speech Movement at Berkeley because a flashpoint for the forces of reaction. So the idea that somehow the counterculture/the ‘60s/ the “hippie dream” dies over the course of two nights in August 1969 is, to paraphrase Joan Didion, a story we tell ourselves in order to live. Because otherwise we have to acknowledge that the counterculture/New Left proved pretty ineffectual when it came to offering a successful alternative to the conservative movement that has its amazing victory with Southern California homeboy Richard Nixon’s election in 1968—here’s one reason among many to love the movie Shampoo: it makes clear, even after invoking Jay Sebring in Warren Beatty’s character, that the cataclysm came in November 1968, not August 1969.

So Manson was a convenient vehicle to help carry this movement along on its well-established track. But he was just that—a convenient, spontaneously-appearing bogeyman. Lots of shit went South after the Tate-LaBianca murders, but it was not because of them. Plenty about the New Left/counterculture was really just getting going: the Stonewall riots were in June of 1969 and what we think of as the modern gay liberation movement was a 1970s movement. Communes sure came under attack after Manson but new kinds of family arrangements continued to develop. So this brings me to Tom O’Neill. He has spent decades, admirably, hunting down every hint that this right wing attack on the counterculture was so organized that it managed to somehow pluck this incarcerated personality, Charles Manson, out of obscurity to do its bidding. Manson was a bad guy who committed terrible acts in many registers. The notion that he was maybe a CIA asset takes a global truth—the CIA was doing bad stuff ALL over the place—and turns it into a nutty piece of local lore. In a way O’Neill’s book lets us keep focusing on Manson as an avatar of evil. He wasn’t really up to that role.

EN: Following up on that, I find it interesting that Manson—a fundamentally apolitical nitwit—would evolve into a fulcrum for political anxiety. As horrifying as the violence he was responsible for perpetrating was, it really didn’t have much meaning beyond one individual’s criminal megalomania and racial paranoia. As opposed to someone like Jim Jones, who actually brought to bear a reasonably persuasive socialist-utopian worldview based on tolerance, before going absolutely crazy. I find the Jones example far scarier in that sense—an apparently reasonable actor becoming murderously unhinged. Do you think, in a way, that Manson is a misplaced exemplar of the limits and flaws within the counterculture?

JM: Interesting to think about Jones and Manson together—biographer Jeff Guinn turned to Jones after publishing his Manson book some years back! The example of Jones’s interracialsm that Guinn does such a good job of chronicling is a good reminder that there were plenty of folks in the 1960s and beyond who were taking this kind of inclusiveness as a first principle. The African American Studies scholar Geoffrey Jacques had a great Facebook thread going recently in which he outlined just how integrated Woodstock was—giving the lie to the “great white acts” vision that has dominated the 50th anniversary coverage. Manson was definitely some kind of racist and segregationist. He was raised in prison and learned many of the lessons of white supremacy and demographic segregation that obtained in the carceral context. But he did not have a unified vision: he was not George Wallace—or McGeorge Bundy! He did not have the power to do much besides spool out some crazy theories to a captive audience. He was briefly tapped into the actual counterculture during his short San Francisco sojourn. But in Los Angeles he was much more tied in with a species of bohemian celebrity culture. The fact that Manson has scanned as a hippie for so long is the work of badly motivated actors ranging from Vincent Bugliosi to Joan Didion to Greil Marcus: pretending that Manson had anything to do with the hippies of the Haight or Laurel Canyon or Woodstock is a pernicious lie that gets repeated over and over—not to discredit Manson, because well, that’s been taken care of—but to discredit the hippies.

EN: One thing you discuss in your book which I find compelling is the implicit and toxic sexism of the hippie counterculture which found its full expression in cults like the ones led by Manson and Mel Lyman, but which really was a feature of the culture more generally: “free love” as a shorthand for treating women as objects to be used and discarded. I’m curious to know, from your perspective, how an ostensible liberation theory evolved into just another means of diminishing women and re-asserting gender inequity?

JM: There are two ways I want to answer this question. The first is to say that I’m not sure that what we generally refer to as the counterculture ever had gender liberation baked into its central mission. Of course there is a Venn Diagram of “counterculture” and “Second Wave feminism” that covers plenty of terrain. But the women’s movement was distinct from—and not infrequently at odds with—the male-driven New Left and counterculture. The great photographer Lisa Law and so many other crucial players in the counterculture speak firmly about how fully the patriarchy was reproduced in these spaces. I spend a decent amount of space in my book talking about a heart-wrenching essay by Ellen Herst published in 1972 in a Boston alternative paper and called “Mel & Charlie’s Women.” Herst—and I simply have not been able to find out who she was, maybe this was a pseudonym—basically argues that Manson and Mel Lyman, a Boston-based cult leader were the fullest expressions of countercultural misogyny. Herst’s work is shattering: she works from an assumption that her female readers will totally know what she is talking about as she outlines the daily hurts of being a woman in the counterculture. It’s brutal and you can read it right here.

But the other thing I want to say is that thanks to scholars like Gretchen Lemke-Santangelo (Daughters of Aquarius) and Lisa Rhodes (Electric Ladyland), novelists like Emma Cline and Allison Umminger, and filmmakers like Mary Harron and Guinevere Turner (Charlie’s Girls) it has become much more possible to understand that even under these conditions of male-dominance, it was quite possible for women to find other and create meaningful, sustaining bonds. That is one of the great insights of this newer generation of scholars and artists: Manson and Lyman, and Stephen Gaskin at the Farm in Tennessee, and so on, were invested in reproducing the patriarchy. But this does not mean that the women around them found it impossible to resist, create pockets of female-directed activity, and on the whole, find a deal that maybe was better than the one they left behind in their family of origin. So, it’s complicated!

EN: An interesting point you make which I had not previously thought of, is the manner in which the rock establishment essentially abandons hippie utopianism following the Manson murders, but that those ideals are picked up on and in many ways improved by soul and funk performers in the ‘70s, ranging from George Clinton and Parliament/Funkadelic all the way through Chic and disco, where Nile Rodgers restores the term “freak” to a place of pride on the disco track “Le Freak.” Is it fair to say that acts like these were able to separate out the positive, outsider-championing elements of the hippie ethos while leaving aside the more disturbingly classist and culturally performative elements of the movement?

JM: Right. I probably ran through this too quickly in the book and I probably make it sound too mechanistic—the white musicians swear off “freak” and the Black musicians, swoop in to save the day. I think “freak” as word and concept had been in lots of Black music: I’m sure you could create a reasonable genealogy that stretches at least back to the dirty blues of the 1920s. But I was trying to extend my argument about the fairly widespread backlash against hippies and freaks on the part of the well-entrenched white musical establishment in the wake of the murders: people like Dennis Wilson and Terry Melcher and Jack Nitzsche and Van Dyke Parks and John Phillips wanted to make it clear that these freaks were NOT their people. And this happened to correspond with a great soul/funk moment when people like Clinton—obviously drawing on the work of Sly Stone and electric Miles Davis—were seeing all kinds of artistic and commercial possibilities in embracing the freak.

EN: Part of the insanely complicated backdrop for the Manson murders was his belief that a violent uprising among African-Americans was looming on the horizon. Another point you make in your book which I had not previously encountered is that while Manson was clearly delusional and insane, the extent of his anxiety about racial violence in Los Angeles in 1969 was not entirely baseless within the context of the moment. Can you explain some of the factors taking place at the time that would have fed Manson’s paranoia about what he felt was a looming race war?

JM: Can I talk about Aquarius again? I can’t believe how much I’ve ended up drawing from this very bad television show. But Duchovny and company capture how completely Los Angeles, in 1969, was defined by racism, racial paranoia, and dread. In January of that year there was a shoot-out at UCLA between members of the Black Panther Party and members of Ron Kaurenga’s US organization. We know now that the FBI was very much involved with helping to create this battle, which resulted in the deaths of two Panthers, Bunchy Carter and John Huggins. And while we are pretty sure Manson was not exactly sure who the Black Panthers were, we know that his alliance with various scary motorcycle club guys was at least, in part, meant to protect him from these forces of Black evil. But however politically benighted Manson was, he must have been hearing about the racial strife in various American cities: one way to periodize this era is by starting with the Watts Rebellion in 1965—right there in Los Angeles. Every summer brought explosive racial violence—very often kicked off by an act or series of acts of police brutality. From Chester Himes to NWA and beyond we have a tradition of Los Angeles-based art that explores how much the landscape was defined by white supremacist violence committed by the police. How much of the racial conflict was present in Manson’s life is not clear: we know he had one very fraught interaction earlier in 1969 with a guy named Bernard Crowe, who Manson believed had burned him in a drug deal. And Manson’s response was to shoot that Black man.

EN: One of the complicated figures to emerge from the Manson story is Vincent Bugliosi, the prosecutor from the LA district attorney’s office who successfully prosecuted the Manson case and later wrote the best-selling account of the crime spree Helter Skelter. What is your view of Bugliosi with the vantage point of history? Do you see him as an opportunist, a stalwart civil-servant or something else entirely?

JM: Yeah, Bugliosi. Tom O’Neill’s book is actually quite good at capturing how fully Bugliosi came to believe he had the copyright on the Manson story and obsessively, litigiously protected his sense of the positive role he played here. I guess what I most want to say about Bugliosi is that he was some kind of genius: I’ve been shocked, in this summer of the 50th anniversary, to see how many of the folks in my social media bubble—good Leftists, anti-mass incarceration, et cetera—are still fully in Bugliosi’s thrall. The book—and miniseries—were huge: if you go back and reread the book and remember how it freaked you out when you were 12 it will be a disappointment. It’s pretty flat and has been passed on the highway by much gorier and detailed works. But Bugliosi’s logic—especially the “Helter Skelter” theory or apocalyptic race war—keeps getting repeated as gospel. By, like Boots Riley! Why could Boots Riley repeat what is essentially cop-knowledge-on-steroids? I know you know that Mekons line about how turning journalists into heroes takes some doing. So I’ll just leave this question by saying the same thing about Bugliosi: he turned himself into the hero of the story. And he really was a petty square who made his bones with this case and then appointed himself Big Boss of Manson. But he was just tall—compared to Manson. That’s all.

EN: Finally, I’m honor bound to ask what you made of Once Upon A Time… In Hollywood and its ostensibly corrective historical measures? Like so much of Tarantino, I enjoyed the picture while grasping immediately why others might recoil from it. How did you think it succeeded in wrestling with the Manson mythos and was there anything about it that particularly surprised you?

JM: I’ll start with the credits: QT thanks Debra Tate, sister of Sharon Tate. As far as I know this is the first piece of Manson Art that anyone in Tate’s family has approved of. So that right there makes QT a wizard, a true star. And (FOLKS YOU KNOW SPOILERS ARE COMING RIGHT?) all he had to do was create a counternarrative where Sharon Tate gets to live—and be the unofficial crown princess of the New Hollywood while those dirty hippie girls get torched. It’s not just that Sharon Tate gets to live, but the death penalty which was handed down at the trial is finally carried out.

Mostly I felt like this was some sort of apotheosis of the backlash rhetoric and art that I spend so much time talking about in the book. These Spahn Ranch hippies are so dumb! And dirty! And horny! They really can’t be allowed to walk among decent folks anymore.

The climax of the movie finds representatives of the Old Hollywood and the New Hollywood preparing to have a drink to celebrate the apocalyptic violence that has just ensued—which resulted in a handful of dead hippies and the remasculinatization of a tired old Western star. If you are gonna reinvest an aging Western Star with phallic power in 2019—well give me Bruce Springsteen’s tired old stunt man taking the little blue pill over Tarantino’s guns-blazing, wife-killing Cliff. I’m all for counterhistorical narrative: it can open up space for intellectual work and cultural action that had seem foreclosed. But this is just triumphalist flexing.