Erik Visits an American Grave, Part 194

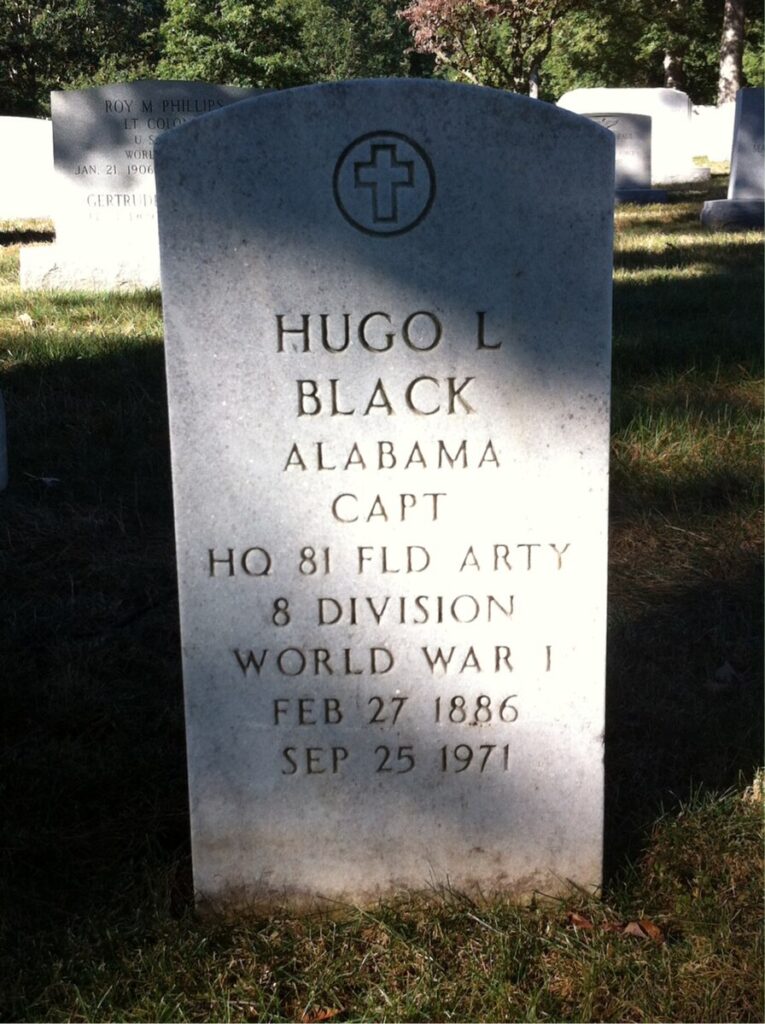

This is the grave of Hugo Black.

Born in 1886 to a poor family in Ashland, Alabama, Black had an older brother who became a doctor and suggested his brother follow in his footsteps. That didn’t quite happen, but Black went to the University of Alabama School of Law, despite not having graduated from high school, and graduated there in 1906. He moved back to Ashland and started a law practice the next year. There wasn’t much interest in lawyers in Ashland and he moved to Birmingham the following year. There he specialized in labor law and that interest in working people would go far to define his career. He served as a captain in World War I and then returned to Alabama. He also made the regrettable choice, so common among middle-class white men of his generation across the nation to join the Ku Klux Klan. This was very much not just a southern thing in the 1910s and 1920s. The KKK briefly controlled politics in Oregon, Colorado, and Indiana, where it was the most powerful in the country.

Black was also politically ambitious and in 1926, he ran for the Senate to replace the retiring Oscar Underwood. Of course the Democratic primary was all that mattered in Alabama. He won that and quickly became a major player in the Senate, pushing harder than nearly anyone in the Senate for economic populism, albeit one that just applied to whites. He first took on the issue of lobbying, which he tried to limit. He became most known for his advocacy of the 6-hour day and 30-hour workweek during the 1930s. Black basically laid much of the political groundwork for the Fair Labor Standards Act through these actions, which was passed in 1938, the last major piece of New Deal legislation that happened in no small part, and against growing opposition to FDR, because of Black, even though he had left the Senate by that time. Black in fact was one of the few southern senators who was fully on board with all parts of the New Deal, including the court-packing scheme, which he argued for by saying that the Supreme Court was unconstitutionally overruling legislation passed by large majorities.

Of course, the court-packing scheme did convince a lot of the old guard to retire. When Willis Van Devanter stepped down in August 1937, FDR named Black to replace him. He had some trouble getting through because his KKK membership was exposed and that caused some to vote against him. Black repudiated that era of his life, but it caused him real political damage. On the other hand, Black was close to NAACP head Walter White. And even though Black had opposed federal anti-lynching legislation while in the Senate, as did all southern politicians, he frequently ruled for black defendants while on the Supreme Court, such as in 1940’s Chambers v. Florida, where black defendants had been denied due process. In his early years as a justice, Black fought to stop the Court from overturning congressional legislation with strong support, reflecting his positions about New Deal legislation.

From a progressive perspective, Black’s rulings were mixed. He wrote the opinion in the atrocious Korematsu decision. That’s unforgivable. He dissented on decisions that upheld requirements for union officials to sign non-communist affidavits. He dissented on Griswold, not seeing a privacy right in the Constitution, another unfortunate decision. This reflected his overall belief in the literalism of the Constitution. But by and large, he was among the most liberal members of the Court, especially by the 1950s. Yet he never repudiated his southern stance and was not good on some cases around civil rights in the 1960s while at the same time supporting aggressive desegregation actions. He read the Civil Rights Act and Voting Rights Act narrowly but not only joined in Brown’s unanimous decision but also called for the Court to institute immediate desegregation in 1969’s Alexander v. Holmes County Board of Education. He also thought states had every right to institute a poll tax and ruled that way in the 1930s and the 1960s. He was also a major defender of the First Amendment and opposed religious teaching in public schools, even though he himself was a long-time Sunday School teacher in an Alabama Baptist church. At the same time, he hated protestors and was hesitant to help them through his opinions. This was a man who personally despised pornography and yet refused to even admit the possibility the governor could censor it.

While Black’s decisions on race and civil rights were mixed, there was no room for subtlety among the white South who considered that very proud southerner a traitor to his people and his region. And for his time and his region, Black is among the most liberal justices in comparison to what one would expect. Not only did he fly in the face of segregation despite being from Alabama, but his opinions on restrictions on speech in the McCarthy era was a noble counterweight to the overwhelming anticommunism placing a dark pall over the nation.

Black stayed on the Court until the very end of his life, resigning eight days before his death in 1971.

In short, Black was a complicated man who was a great populist on labor issues and completely conflicted on racial issues, a former Klansman who couldn’t repudiate poll taxes but could repudiate segregation while championing free speech in a pure form for nearly everyone except protestors. Such is the duality of the southern thing.

Hugo Black is buried on the lands of the traitor Lee, Arlington National Cemetery, Arlington, Virginia.