“Nothing has been added but sentences”

Before Thomas Chatterton Williams’s book hits the remainder tables next week, we should appreciate this very fine piece of writing by Andrea Long Chu:

On February 18, 1965, students at Cambridge University assembled for a debate between James Baldwin and William F. Buckley Jr. on the topic of racism in America. Before a rapt audience, Baldwin spoke of not only the stolen labor of slaves that had enriched the Southern economy but also the daily humiliations of being Black — “the policeman, the taxi drivers, the waiters, the landlady, the landlord, the banks, the insurance companies, the millions of details 24 hours of every day which spell out to you that you are a worthless human being.” Buckley, in his famous mid-Atlantic sneer, responded that the economic condition of Black Americans had risen so greatly since slavery that they had, essentially, nothing to complain about. Of course, Buckley was lying through his teeth: Almost half of all Black Americans were living in poverty. His real disagreement with Baldwin lay at the social level. The odious behavior of a few individual whites was regrettable, but it was no great obstacle. The real problem was that Black people lacked the kind of serious moral and intellectual “energy” necessary to produce a professional elite. Instead, the civil-rights movement had encouraged a self-defeating posture of victimhood.

Almost half of all Black Americans were living in poverty. His real disagreement with Baldwin lay at the social level. The odious behavior of a few individual whites was regrettable, but it was no great obstacle. The real problem was that Black people lacked the kind of serious moral and intellectual “energy” necessary to produce a professional elite. Instead, the civil-rights movement had encouraged a self-defeating posture of victimhood among Black people that young white liberals were all too eager to affirm. Thanks to the “generosity” of white Americans, Black people had already attained economic justice, Buckley suggested. The last thing they needed was social justice too.[…]

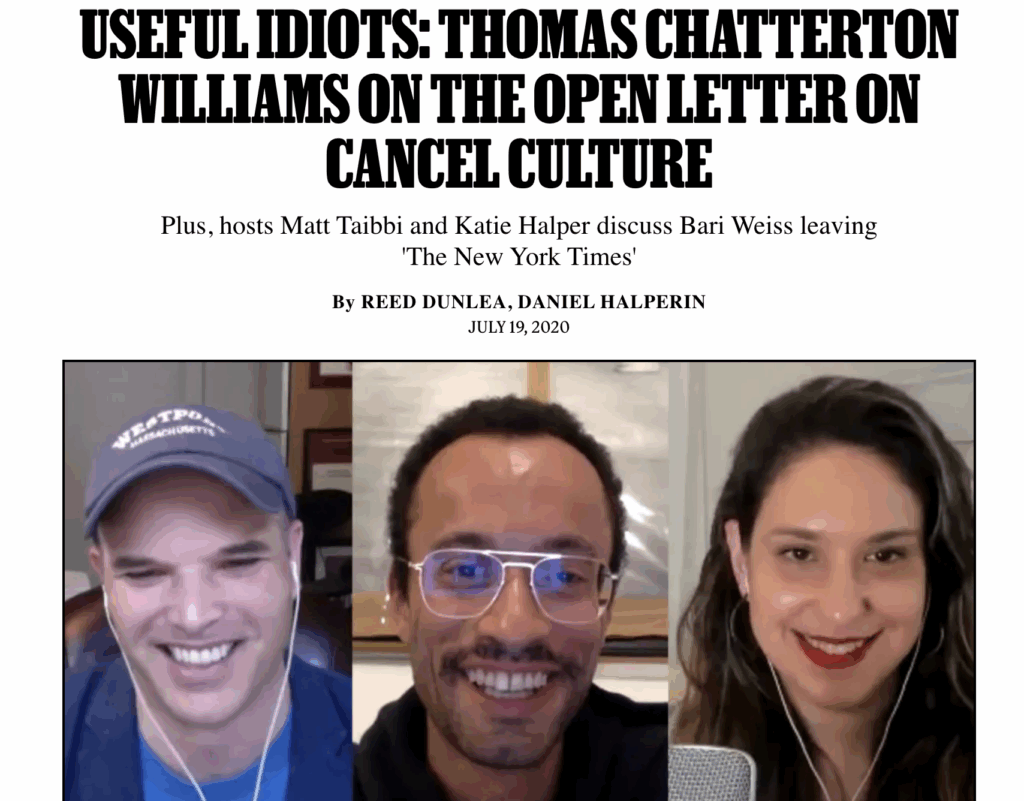

Critics of social justice sensed an opening. Later that summer, Harper’s magazine published an open letter warning that the ongoing unrest was weakening liberal norms of tolerance and free thinking in favor of “ideological conformity.” The letter, whose high-profile signatories ranged from Noam Chomsky to J. K. Rowling, ruffled all of the intended feathers, even if its successful brandishing of elite influence in the pages of a prestigious magazine deflated its own claims of chilled speech. The open letter was spearheaded by the writer Thomas Chatterton Williams, author of a memoir about “unlearning race” who liked to position himself as a centrist foil to Ta-Nehisi Coates, that bard of Black despair. Indeed, Williams was a Black dissenter in the mold of Albert Murray or Glenn Loury, the sort of anti-woke intellectual it would have been necessary to invent had he never managed to exist. (His first book, Losing My Cool, was about the deleterious effects of “hip-hop culture” on Black youth.) In the coming months, Williams would warn that a multiracial, college-educated social-justice movement had made George Floyd into a vessel for its endless litany of grievances. If Baldwin were alive today, he claimed, he would be forced to admit that the “criminal indifference” of white people 60 years ago (Baldwin’s phrase) has been replaced not by goodwill and human feeling but by the ruinous pursuit of an “ever more ineffable kind of social justice.”

Now Williams has written a book about the long hot summer of 2020. He has often imagined himself an heir of Baldwin; here, he could not sound more like Buckley. Summer of Our Discontent: The Age of Certainty and the Demise of Discourse offers a roughly chronological account of the past two decades, from the 2008 election to the protests for Gaza. But editorial indulgence has resulted in such a sludge of footnotes and block quotes that the eye must often dismount and continue on foot. The reader will find here no argument she could not have inferred from the titles of a dozen identical books on wokeness; nothing has been added but sentences.

The are many more good one-liners here, but what makes it worth reading (despite the fundamentally easy target) is that it so much smarter about the “free speech” debates than any of the interchangeable arguments you get from the “anti-woke” crew:

This is why the enemies of cancel culture cannot help but compare the firing of Hollywood directors to witch hunts. They implicitly understand canceling as a distinctly social harm, rather than a strictly economic or political one. After all, when Williams chides Obama for choosing to be Black; when he rebukes corporations for their woke HR initiatives; when he speaks balefully of sensitive college students — what could he possibly be asking for if not a more socially just world? For Williams, this would entail a “maximally tolerant society,” the kind where values of free expression and the open exchange of ideas are not only protected but “inculcated” in children by their parents. This is an amusing word choice for a man who hates orthodoxies of all kinds. But tolerance, he writes, works best when “buttressed by agreed-upon standards and a common investment in informal norms.” That is, Americans cannot have social justice until we first come to a consensus about what not to tolerate. (The Harper’s letter notably did not include any far-right signatories, for instance.) I cannot imagine any social-justice warrior disagreeing on this point. The question is who gets to contribute to this consensus — and who does not.

As we’ve said before, virtually nobody actually believes that “free speech” means “access to any platform of your choice to say anything,” not least because this would be literally impossible. And for people in the general orbit of Bari Weiss Cottonghazi is an excellent illustration of the inherent incoherence of these arguments:

In the early weeks of the George Floyd protests, the Times published an “Opinion” piece by Senator Tom Cotton urging Trump to “send in the troops.” The essay provoked immediate backlash online, with some Times employees staging a virtual walkout and tweeting that the piece endangered Black people. Within days, the paper had issued a rare apology and secured the resignation of top “Opinion” editor James Bennet. For Williams, Bennet’s dismissal signaled a genuine “crisis of democracy,” a sign that the most respected paper in America had betrayed its commitment to free speech, “the bedrock for all subsequent rights and assurances” in a liberal society. Williams regards Bennet as the victim of a “multiethnic mob of junior employees,” some of whom were “not even journalists” but mere tech workers. Never in the paper’s history, he breathlessly claims, have its employees so brazenly dared to “mutiny their bosses.”Now really, captain — mutiny? This is the language of a company man, not a freethinker. The worst injustice here appears to be the spectacle of privileged staffers openly defying the elite institution they were lucky to call their employer. (Williams was a contributing writer at The New York Times Magazine from 2017 to 2021.) The ousting of a single editor by his subordinates strikes Williams as far graver an affront to liberal democracy than the prospect of a would-be dictator unleashing the most powerful military in the world on American cities. Because the Times, he tells us, is one of the most important cultural institutions in the world; it cannot be handed over to the undeserving. “One immense side effect of social justice activism is the redistribution at scale of recognition and enrichment,” Williams writes, noting that Bennet had been a credible candidate for the newspaper’s top job. This is what the mutineers were really after: influence, prestige, and employment opportunities that they had not earned. The only difference between uppity Times staffers in Midtown and the roving bands of looters in Soho was that the law actually allowed looters to be roughed up by the police.

“[T]he language of a company man, not a freethinker” captures this entire genre perfectly. You can believe in a robust, open discourse, or you can believe that a newspaper’s staffers cannot criticize the decisions of the editors make about what to publish, but not both.

As Mychal Denzel Smith observes in his own excellent review, like so many self-styled FREE SPEECH WARRIORS his argument inevitably boils down to “it is bad to platform ideas that are in strong contradiction with my priors and it is bad to criticize the platforming of ideas that are consistent with my priors”:

It would perhaps be more intellectually consistent for Williams to assert that every idea, no matter how fringe or outlandish, must be heard across every institution, and that there should be no consequences for any of it — Nazis should publish op-eds in major newspapers, Five-Percenters who believe White people are devils should host cable news shows, etc. But he’s not this type of free-speech absolutist. Few people are. Williams doesn’t hide his disdain, for example, for NPR allowing the anarchist writer Vicky Osterweil to present an argument in favor of rioting and property damage as a form of protest. But he found the widespread criticism of Sen. Tom Cotton’s New York Times op-ed published at the height of the 2020 protests, “Send In the Troops,” in which Cotton called for the federal government to confront the demonstrations with the military, to be laughable, an overreach of online progressives. In his estimation, it is the responsibility of an institution like the Times to publish such arguments, and Cotton’s view, he says, reflected the feelings of a majority of Americans who wished to see an end to protests that had damaged property and businesses. Which is to say, it was an op-ed that confirmed Williams’s political priors, and so he had no issue with it. Which is, again, what he accuses those to his left of being susceptible to.

I won’t criticize publishing Knopf for providing this platform, though — given that the book as already outside the top 10,000 on Amazon despite being heavily discounted, the advance should be punishment enough.