This Day in Labor History: November 21, 1896

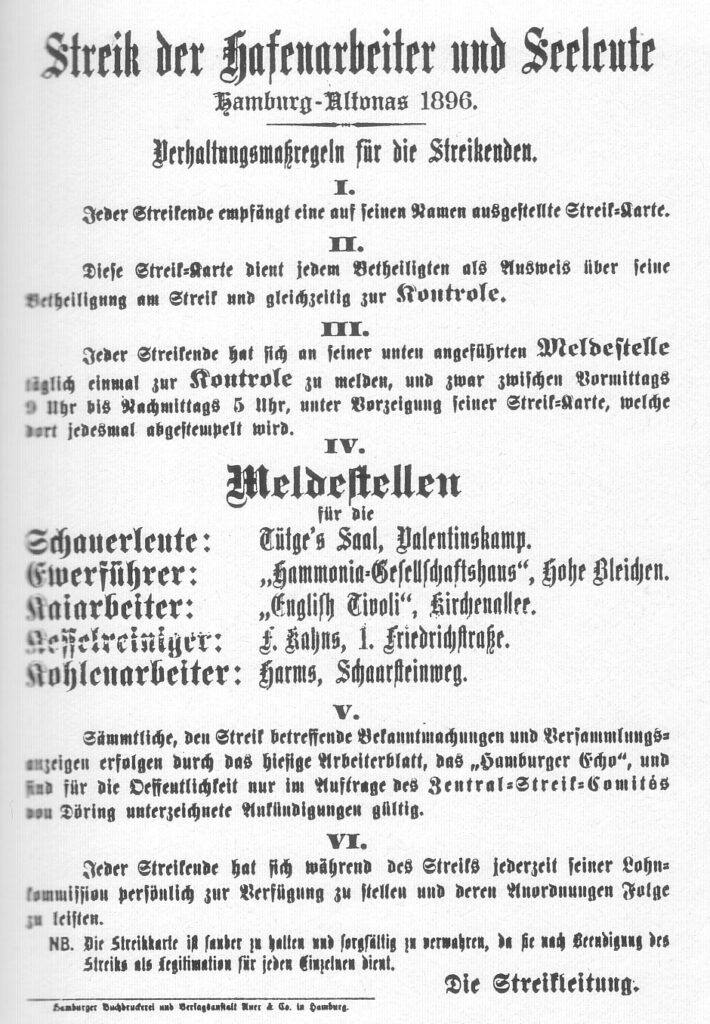

On November 21, 1896, dock workers in Hamburg, Germany went on strike. One of the major working class struggles in German history, the conservative leadership of that nation went ballistic over the sheer existence of these workers striking. The strike failed, but it was also an important moment in the development of international solidarity efforts.

Hamburg was a hugely important port in Germany going back to the early 19th century. By 1873, the port accounted for 30 percent of German shipping traffic. This critical hub also made it vulnerable to worker activism, since striking the docks in some ways meant striking Germany as a whole. The entire country was reliant on the port for its economic livelihood.

Unsurprisingly then, Hamburg was a center of trade unionism. It was nearly a wall-to-wall union city by the 1890s, though what power those unions really had was not always clear. But the workers party–the Social Democratic Party–had all of Hamburg’s seats in the Reichstag, so they were politically organized.

Now, workers in Germany had a similar demand to many workers around the world in the 1880s and 1890s–the eight hour day. This was truly the first universally held goal by huge swathes of the working class. But like in the United States, German employers sharply resisted this and a series of strikes in 1890 did not win it for them. So it was an unmet demand in 1896. This also lowered the power of the trade unions in Hamburg, since the crushing of the workers’ dreams meant many didn’t really believe unionism could achieve the power they demanded. But there were also histories of successful organizing, particularly coal workers in 1889.

The economic downturn of the 1890s affected the Germany dockworkers too, but by 1896, things were looking up in Germany and increased hope meant increased demands. There was a lot of grain being produced that was sitting on the docks. This all led to a new wave of organizing. The old belief that workers tend to organize when things are looking up than when they are at their worse usually proves to be true. An English organizer named Tom Mann was in Hamburg and leading a lot of this organizing. There was a lot of international organizing going on in these years. He was successful, so the government expelled him from the country, angering the workers. Through November 1896, the workers debated striking and finally those in support won out. They walked out on November 21.

The local employers association took it on themselves to defeat the strike. They imported 2,000 strikebreakers by December 7. They were met with violence from strikers, determined to protect their jobs from these scabs. But the employers had a big ally–Kaiser Wilhelm II. He told one of his generals to intervene, saying “Just go ahead and do it, even without asking.” Carte blanche to crush the strike. Most of the government agreed. But it wasn’t just sending in the army. It was a slow crushing, mostly using the power of the law to make it impossible for them to continue.

The Hamburg workers tried to reach out to other German workers, but didn’t succeed very well. By this time though, there were a lot of connections between the different European union movements. Dockworkers in Stockholm, Bristol, and Hull, as well as in a few French ports, agreed not to unload ships from Hamburg they thought were loaded by scabs. There were sympathy strikes in Amsterdam and Rotterdam and the Swedish union movement attempted to stop the migration of any worker who might head to Germany to scab.

There was also some donations. The actual point of solidarity as it was articulated in the late 19th century, when they word was coined, was mutual aid, usually financial, for strikers. So the dockworkers and other sympathetic unionists tried to donate. But it was so hard to raise enough money–it cost a lot to feed families, not to mention run the strike, intimidate scabs, print propaganda, and all that stuff. Aid came to about 69,000 marks. But it needed 1.75 million marks over the next three moths. The government made it illegal for the union to collect contributions door-to-door.

Meanwhile, the government cracked down hard on any worker accused of violence against scabs. About 500 strikers were arrested for this, whether they were involved in such actions or not. Strike leaders went to the German Senate in mid-December to ask for mediation, but the Senate sided with employers and said that was only possible if it was not binding and also if the strike ended first. Still, the leaders recognized it was probably lost and urged workers to accept this. But the workers were not yet ready for that. About 70 percent of the workers voted to go on. Workers inability to get machinists to join them helped undermine the strike. The machinists thought themselves superior workers and these craft divides undermined so many strikes, in Germany and elsewhere.

In fact, by January, some employers were willing to deal. But the strikers were also getting tired. Maybe if they had held out a little longer, they might have won something. There was a last minute appeal from German academics which led to some money being raised for the workers. But this backfired and hardened the softening employers’ positions. Meanwhile, workers were hungry and they were cold. Striking in Hamburg in January is not fun. More scabs started appearing from other parts of Germany.

Ultimately, it was just not possible for the dockworkers to go on. The union called off the strike in February 1897, though not before multiple votes finally convinced workers that they had lost. This certainly did not destroy the union though. In fact, just a few months later, those workers were raising money for metal workers striking in England. Those workers didn’t win much either. But the financial capability was just too much for unions to overcome, even with foreign assistance.

Also, the union actually grew out of this. More dockworkers joined the union in the aftermath, impressed by the level of strength and solidarity shown. But the union itself got pretty scared to strike in the aftermath, as the state and Kaiser especially wanted to use power to repress workers’ movements entirely. Finally, after 1898, some employers began accepting the principle of collective bargaining, figuring that such agreements with unions would reduce striking, which is the point after all. By 1913, the entire port had collective bargaining agreements.

I borrowed from Nicholas Delalande, Struggle and Mutual Aid; The Age of Worker Solidarity to write this post.

This is the 582nd post in this series. Previous posts are archived here.