Gaming Notes

I’d like to say that a new games review roundup is your reward for reaching the LGM fund drive goal. But really, it’s a reflection of the fact that, after two or three months of not feeling compelled by any new game, I spent the long holiday weekend riffling through my Steam library, firing up games that I bought a year or two ago and then never touched. As you can see below, not all of the resulting gaming experiences were positive ones, but at least we got a blog post out of it.

Before we get to the reviews, the now-traditional Golden Idol update: in my last Gaming Notes post, I rhapsodized about Rise of the Golden Idol, the sequel to the already excellent The Case of the Golden Idol, which continues that game’s idiosyncratic and delightful approach to pulp mystery. Developers Color Gray Games promised to expand Rise‘s story with additional mysteries, and in the last few months they have delivered: The Sins of New Wells, which functions as a coda to Rise‘s story, was released in March, and The Lemurian Phoenix, which fills in a major character’s backstory, last month. Both are fantastic as both stories and puzzles, and only further cement this series’s place in the pantheon of modern puzzle games.

As usual, consider this post an open invitation to talk about your own recent gaming. How many unplayed games are in your Steam library, and what will it take for you to finally play them?

The Roottrees Are Dead (2025)

Dedicated readers of these posts may recall that I already reviewed this game in late 2023, in its free, web-based version. At the time, I said of The Roottrees Are Dead, a logic puzzle inspired by Return of the Obra Dinn (2018) and Her Story (2015), that it was so compelling and well-crafted that surely a commercial version would soon be in the works. Happily, it hasn’t taken very long for this to materialize. Joining forces with designer Robin Ward, original developer Jeremy Johnston has preserved the original game’s setup—in which the player must untangle the titular family tree, searching through databases, periodicals, and books in order to place each of the descendants of a 19th century candy mogul in their correct position—while making some necessary quality of life improvements. Most importantly, the original game’s AI-generated graphics have been replaced (Johnston cited the use of AI as the reason he offered the original game for free, and I think if this was the use case for the technology, as a placeholder to drum up investment money with which to pay actual artists, it would be far more defensible than it currently is). But the process of identifying the various Roottrees—searching the web, identifying sources that might contain relevant information, poring through pieces of evidence, and placing the results on the family tree—has been streamlined and made more intuitive. The result is the same excellent game with a new coat of paint, and well worth a look if, like me, you are obsessed with the subgenre of story-based logic puzzles that has flourished in Obra Dinn‘s wake.

If this were all the new Roottrees had to offer, however, I might not have bothered reviewing it again. But somehow, in a little over a year, Johnston has also managed to add an additional layer of story and puzzles that is essentially a whole second game. In the wake of the original game’s events—in which your work uncovered a long-hidden Roottree secret—the world has become consumed by “Roottreemania”, with multiple people emerging from the woodwork claiming to be illegitimate Roottree scions. This makes an amusing conceptual twist on the original game, which required you to work out the history of a family that was obsessed with legitimacy and blood connection. But it also subtly changes the sort of work you need to do to solve the game. Instead of tracking down records of marriage and people proudly boasting about their heritage, you need to figure out whether a particular woman worked as a certain Roottree’s secretary at the right time, or whether a marriage broke down because of an affair.

The new Roottree puzzles up the difficulty level by quite a bit, to an extent that I eventually found a bit wearying. There’s such a glut of information, and so many avenues of investigation to follow it down, that you can eventually lose patience with the process, with having to decide, of each new name or company or event, whether you should search for it online, or in the archives of four or five different periodicals. Happily, one of the additions Johnston has made to the game’s interface is an extremely helpful and intuitive hint system, which keeps track of the evidence you’ve discovered and the searches you’ve conducted, and can point you in the direction of the next step in your search without making it feel like you’re not doing the work. At the end of the revamped game, there is an indication that Johnston might expand the puzzle even further, to other parts of the Roottree family tree. If this version is any indication, that too will be a pleasure to play.

Thank Goodness You’re Here! (2024)

Barnsworth, the small Northern English town where the zany antics of Thank Goodness You’re Here! take place, feels like a place plucked out of a long-ago time—or, perhaps, out of a particular type of mid-century British comedy. Its residents debate the kind of beans they prefer for breakfast, and start feuds over whether to serve a large or small pie for their tea. The local chippie failing to open for the day is a matter of some scandal and public debate, and any missing tradesman can be found at the pub drinking their morning pint. Humor manages somehow to be both racy and vegetable based, and overheard punchlines include such bon mots as “in arrears? Well, I’ll try, but it’s your wife.”

The player discovers all this by sending a visitor to Barnsworth—a small visiting salesman who has decided to wander the town while waiting for a meeting with the mayor—on a series of quests for the townspeople, each of whom greets him with the titular phrase and immediately dispatches him on an errand: to work out why the watering hose for the allotment isn’t delivering water, or find a handyman’s missing tools, or deliver meat to the local piemaker. Unraveling these tasks often takes a turn for the psychedelic and the surreal—you find yourself exploring the secret society of the city’s rats, or plumbing the psyche of the butcher and his fraught relationship with meat production, or crawling through sewers, drainpipes, and chimneys.

The idea of taking the conventions, character types, and gags of a random episode of Dad’s Army or Fawlty Towers, porting them over to a 21st century platformer, and then considerably upping both the weirdness and lewdness quotient (one of the game’s final gags involves a mission to deliver milk for a resident’s cup of tea, which somehow segues into a dip in a hot tub with a cow) is so wild that you have to stand up and salute the game’s creators, the (unsurprisingly) Yorkshire-based studio Coal Supper. The level of execution, too, is impressive, with deliberately-grotesque graphics full of distinctive and humorous detail, and a voice cast, led by Matt Berry, who perfectly understand their assignment and deliver an array of instantly recognizable types. In terms of gameplay, Thank Goodness You’re Here! sends the player on loops through the town’s nonsensical geography (one transition requires you to repeatedly drop down a hapless resident’s fireplace, covering his sitting room with soot as soon as he’s finished cleaning up after your last visit). In each go-around, the available paths and interaction points are changed in subtle but noticeable ways that make progressing through the story, and your current set of tasks, feel intuitive while also giving you a sense of accomplishment.

All that being said, if you’re not steeped in this sort of setting—either the real thing or the cultural edifice that has built up around it—your reaction to Thank Goodness You’re Here! may, like mine, be more a matter of anthropological fascination than genuine delight. This is a game made by a certain subset of English people, for that same subset of English people. The rest of us will, I think, have to settle for admiration for a job well done, as well as genuine awe that this sort of project actually got off the ground.

Lorelei and the Laser Eyes (2024)

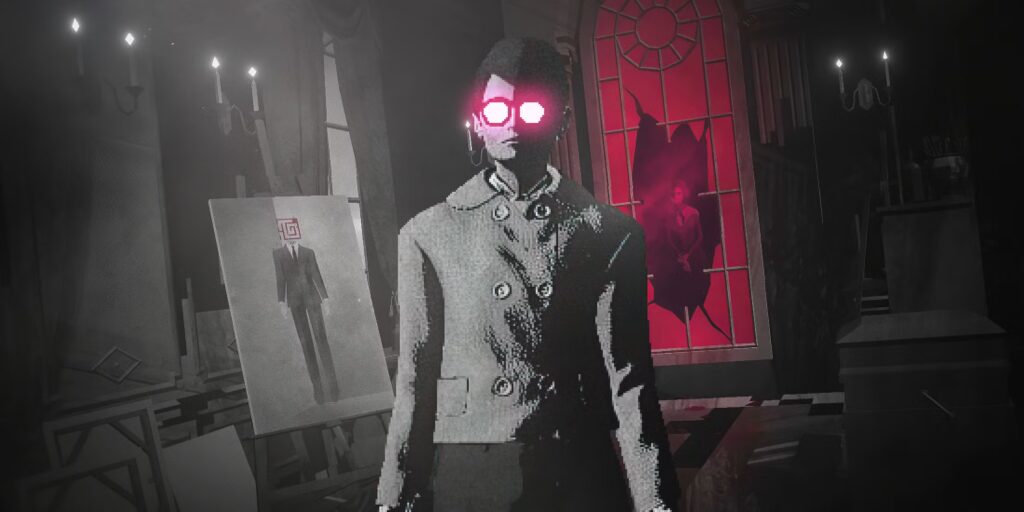

At the beginning of this eerie, impeccably crafted puzzle game, a chicly-dressed woman arrives at a closed-for-the-season hotel in the middle of a German national forest. The year is 1963, and our heroine has been invited to collaborate with avant garde Italian director Renzo Nero. Immediately, things take a turn for the weird. Mysterious figures—a man in a magician’s costume, a woman in an antique dress—appear and just as quickly disappear. The heroine’s room is already occupied, by a dying old woman whose eyes glow red. Nero himself, after making grand pronouncements about how their project will save art from the grasping claws of capitalism, locks himself in his room, demanding that the heroine retrieve his lost script pages—pages that, when they are discovered, describe the deterioration of this artistic collaboration, with the Nero who appears in them quickly losing his grip on reality.

To reveal all this, the player must fully explore the hotel and its grounds, most of which are locked down at the game’s beginning. As the heroine moves through the hotel—a shadowy, greyscale space with occasional, disquieting splashes of red—she encounters keypads, combination locks, mazes, and number puzzles. The puzzles are tough but fair, and solving them often hinges on entering the right conceptual space. The keypad puzzles, for example, mostly have the same password, and the trick is figuring out how the entry system has been altered—in one case, the numbers on the keypad have been shuffled; in another, the player must press buttons as if they were drawing the number on the pad. The more of the hotel you discover, the more you understand about what happened in it, both in 1963 and in the 1847 events which Nero’s film fictionalizes. And the more you learn about those events, the more information you have with which to solve the next puzzle.

The game I found myself thinking about while playing Lorelei and the Laser Eyes was The 7th Guest (1993), the classic haunted house tale that set one of the core standards for videogame horror. Like that game, Lorelei achieves much of its effect through having the player explore a creepy, dimly-lit space, where at every turn you expect to find horror—and where the fact that you instead discover yet more empty rooms is in no way reassuring. (The two games even feature the same mechanic, of a map whose rooms change color as the player gains access to them.) If The 7th Guest was an inspiration for Lorelei‘s creators, the Swedish studio Simogo, they have delivered an extremely clever riff on the original. Unlike the earlier game’s straightforwardly horrific tale of child sacrifice and demonic possession, Lorelei and the Laser Eyes is doing something more slippery. The haunting at the center of its story is the haunting of painful memory; the ghosts the player encounters are the past literally existing alongside the present. Moments of horror are often undercut—splashes of red are usually paint rather than blood; a body in the hotel’s garden turns out to be dummy used in a film shoot. Fiction and reality blend together, and different types of art—Nero’s giallo-inspired movies, the installations by electronic art pioneer Lorelei Weiss that litter the hotel, and even a game within the game that seems to be a prototype of the game we’re playing—are intermingled, raising questions about who, and what, the heroine actually is.

Another similarity between Lorelei and the Laser Eyes and The 7th Guest is the way their gameplay hinges on brain teaser puzzles, whose presence in the game space ultimately feels intrusive—just as you eventually had to wonder why deranged toymaker Henry Stauf had populated his demonic mansion with so many chess puzzles, it raises similar questions when the process of unraveling what happened at the hotel seems to depend on knowing Roman numerals or answering trivia questions. To an extent, this is simply the buy-in of the game—and a major component of its appeal, since the satisfaction of getting through another locked door is immense, whether or not it makes sense for that door to be locked. But the more we learn about events in 1963, and about the nature of the game we’re playing, the more incongruous the presence of the puzzles is. It’s not enough to undermine what is ultimately an impressive, immersive experience, but it’s a niggle that lingers, even after the game reaches its stunning conclusion.

No Case Should Remain Unsolved (2024) & Phoenix Springs (2024)

It’s not often that I write about games I didn’t like in these roundups, for the simple reason that I usually don’t get very far into them. If a game doesn’t find at least some way to grab me within the first half hour of playing it, odds are good that I will put it down, promising to get back to it when I’m in a more suitable headspace, and then just… not do that. So the fact that I made it to the end of both of these games despite not enjoying either one very much speaks to their combination of compelling elements and deep-seated flaws. On paper these are both the type of game I tend to enjoy—that story-based puzzle I mentioned above—and both have been positively reviewed elsewhere. But in both cases, I encountered problems that repeatedly cut into my immersion and investment. At some point, since these are both also pretty short games, it felt easier to just fire up a walkthrough and power my way to the end.

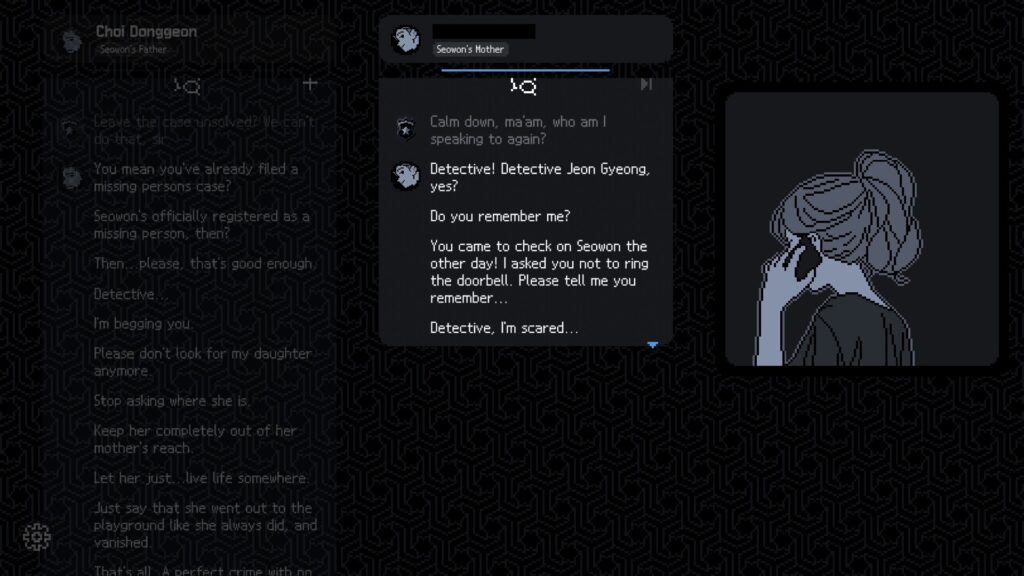

Of the two, No Case Should Remain Unsolved, by Korean studio Somi, comes closer to being a success, since its problems are more in execution than concept. That concept is initially a bit vague—a former police detective steeped in self-loathing, who may be a patient in a mental health facility, and may be hallucinating in the last moments of life, explains to an interlocutor, who may be a police officer and may be the angel of death, that she is haunted by the one case she failed to solve, the disappearance of a young girl. Once the premise is established, however, the game finds a more solid footing when it sets up the means of resolving the detective’s trauma. The player is presented with fragments from interviews the detective conducted while investigating the case, which they must assign to the correct subject, and arrange in their correct order. Doing this unlocks more interview fragments, as well as questions about the case, finally leading to the truth of what actually happened.

The combination of an unfussy gameplay mechanic with a mystery story should have been an instant win from me, but unfortunately in this case “unfussy” actually means “bare-bones” and even “clumsy”. The organization of the interview fragments fills your screen with text which you have to laboriously drag around to find the bit you’re interested in. Unlocking new interview segments requires tracking down a relevant keyword, which in practice means scrolling through the same text again and again. I spent most of the game struggling to figure out how to reorder segments, because the button that does this was too dark against the game’s black background. It feels instructive to compare No Case to The Roottrees Are Dead—a game that started its life as a no-budget lark and which still maintains its extremely minimalistic graphics and interface in its commercial version, but which nevertheless places an emphasis on streamlining the gameplay experience so that players can focus their attention on the mystery. It’s a great shame that No Case doesn’t do the same, because there is a genuinely clever twist at the center of its titular case which it might have been a real pleasure to work out, if I were not, by that point, too annoyed by its cumbersome mechanics to care.

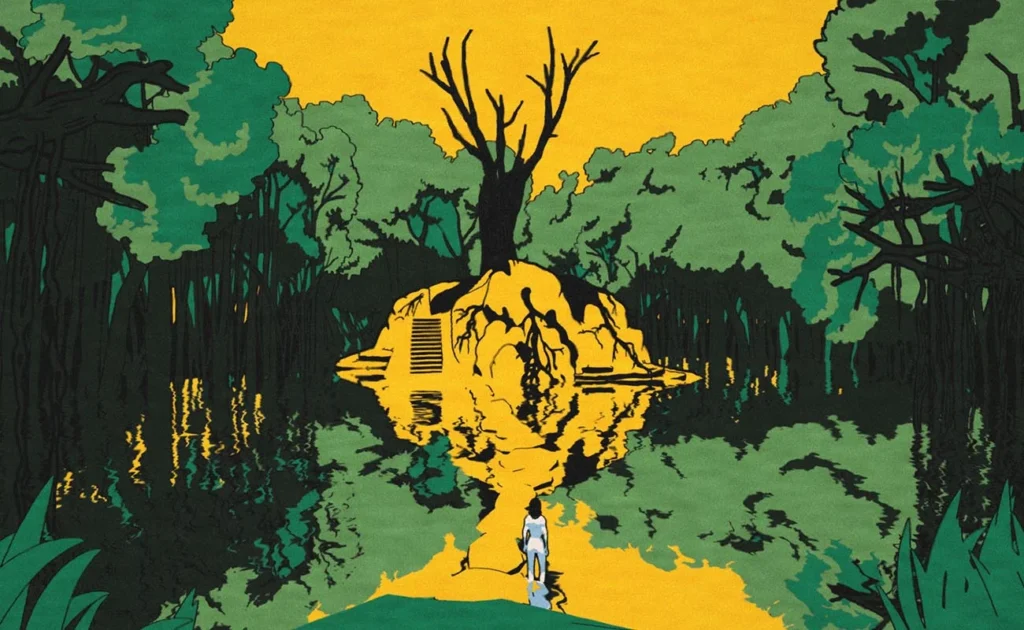

Phoenix Springs, by British-based Calligram Studio, is in many ways No Case‘s polar opposite. On a technical level, it is an absolute joy to play. Its graphics, which feature bold, inky lines and blocks of color in a style that reminded me of silk-screen printing, are gorgeous to look at. Its fascinating setting is half cyberpunk dystopia, half folk horror. And its interface is the epitome of minimalistic elegance. You play Iris, an investigative journalist who is searching for her estranged brother Leo. As Iris collects information relating to Leo’s work as a boundary-pushing bioengineer, text bubbles appear in a repository called “leads”. Progress in the investigation is achieved by combining a lead with an object or person on screen, a single mechanic that can represent actions as diverse as questioning a source, leafing through document stores, or searching the internet. Combined with voice actress Alex Anderson Crow’s dry, unflappable narration of the increasingly odd characters and psychedelic events Iris encounters, this has the effect of making you feel like an old-timey reporter, wearing down shoe leather in pursuit of a hot story.

It’s that story that ends up being the game’s downfall. Phoenix Springs begins in a quasi-realist mode, introducing us to a near-future setting in which ubiquitous surveillance and government control of speech and research have served to criminalize vast swathes of the population. The further Iris’s investigation progresses, however, the more the game descends into weirdness. The titular location is a desert oasis whose inhabitants have lost all sense of self and spend their days performing nonsensical, repetitive tasks. As the narrative skips and starts, Iris’s own sense of reality starts to come into question. All of which might work in another type of a narrative, but in a game whose key mechanic involves asking questions and following them to the next logical step, the fact that the story being revealed is increasingly illogical can feel alienating rather than exciting. (It does not help that at key moments, Crow’s narration is drowned out by music, making me miss what might have been important information—that’s right, the shitty sound mixing that has infected film and TV has now made its way to computer games.) By the time I arrived at Phoenix Springs‘s ending, the whole thing felt so incoherent that I could feel no pleasure in my accomplishment.

Saltsea Chronicles (2023)

There’s a lot of conversation these days, in genre circles and outside it, about what constitutes “cozy”. Is it a storytelling mode, or an aesthetic, or a collection of tropes and plot elements? Personally, I find the term “cozy” too wooly and subjective to be of much use, but every now and then a work comes along that seems to epitomize it. Saltsea Chronicles, from Danish studio Die Gute Fabrik, is one such work. Set in post-climate-collapse future, on a chain of islands that are all the habitable land that remains after massive sea-level rise, it is nevertheless a cheery and deliberately cute game, right down to its construction paper cutout animation. A group of friends who are refurbishing an old sailing vessel are shocked when their leader disappears, apparently carried off by a mysterious ship. Such acts of violence and subterfuge are supposed to be impossible in their society, which has abolished money and private property (“don’t be a hoarder!” is a common exhortation) and where decisions are made entirely by consensus. And yet as the remaining crewmembers follow in their lost friend’s footsteps—traveling from an island where scientists study lost biomes in environmentally controlled domes, to a nonstop party on the slopes of a volcano, to an island whose inhabitants live in symbiosis with cats—they discover increasingly troubling hints that all is not well in their society. A mysterious, oily black substance kills plant and animal life. The lost, feared technology of “engines” appears to be on the rise again. More people seem to have disappeared, and fallen under the sway of a charismatic captain.

The chief pleasure of Saltsea Chronicles lies in how versatile its storytelling is, and how much freedom it leaves the player to direct the course of its story. In every chapter, you can choose which of the clues the crew has collected to follow, and which crewmembers should explore each location. Should you send the grizzled veteran who has maybe seen a bit too much to take the current crisis seriously, or the green newbie who needs to learn how to handle a mission on their own? Should you pair up people who get along, or force crewmembers who have been quarrelling to team up, in the hopes that a shared goal will help them bury the hatchet? A further complication is that not everyone on the ship is entirely likable. The captain is moody and snappish; the radio operator is too wrapped up in their own problems to notice when they steamroll others. You can choose to sideline these characters, or put them in the middle of a story in the hopes that they can work through their issues. Characters you encounter along your journey will sometimes ask to come aboard, which you can grant or deny. Every one of these choices ends up affecting the ship’s dynamic, and in turn, the crew’s ability to work together and make future decisions.

Of course, choice in games is almost always an illusion. If you play Saltsea Chronicles a few times to explore different story paths (an ingenious load/save mechanism allows you to branch off an existing saved game so as not to waste too much time with repetition) you’ll quickly discover how much of its story is actually fixed, with specific story beats that always arrive at the same point, directing the player where the game wants them to go. This, to be clear, is not a complaint: it’s the job of a story to bring you to its ending, and the genius of narrative-heavy games is in making you feel like an active participant in reaching that end, even if it’s not of your making.

It’s in the substance of that ending that Saltsea Chronicles fumbles. As the crew close in on their missing friend, they discover a looming danger to the whole archipelago, and a group who have gone to violent extremes to, as they believe, prevent it. The reaction our heroes have to this new information, and the way they choose to address it, raise a whole host of thorny questions. Is violence always completely unjustified, even in the face of existential risk? Is it possible that a society that prioritizes consensus will struggle to respond to a crisis that demands immediate action? Could that same desire for consensus lead to the ostracism of people who stand out for their scientific curiosity or thirst for adventure? These are not easy questions to resolve, so the way that the game responds to them with categorical statements, and the firm insistence that this way of approaching a complicated problem is wrong, while this way is right, puts the lie to its cutesy aesthetic and sops to inclusivity. Which, to be fair, is a problem I tend to have with a lot of cozy fiction, so it’s not a great surprise to discover Saltsea Chronicles falling prey to it. But it means that at the end of a story that has pulled you along with its myriad possibilities, you discover a conclusion whose dogmatism makes the prospect of exploring those possibilities seem distinctly less appealing.