Erik Visits an American Grave, Part 883

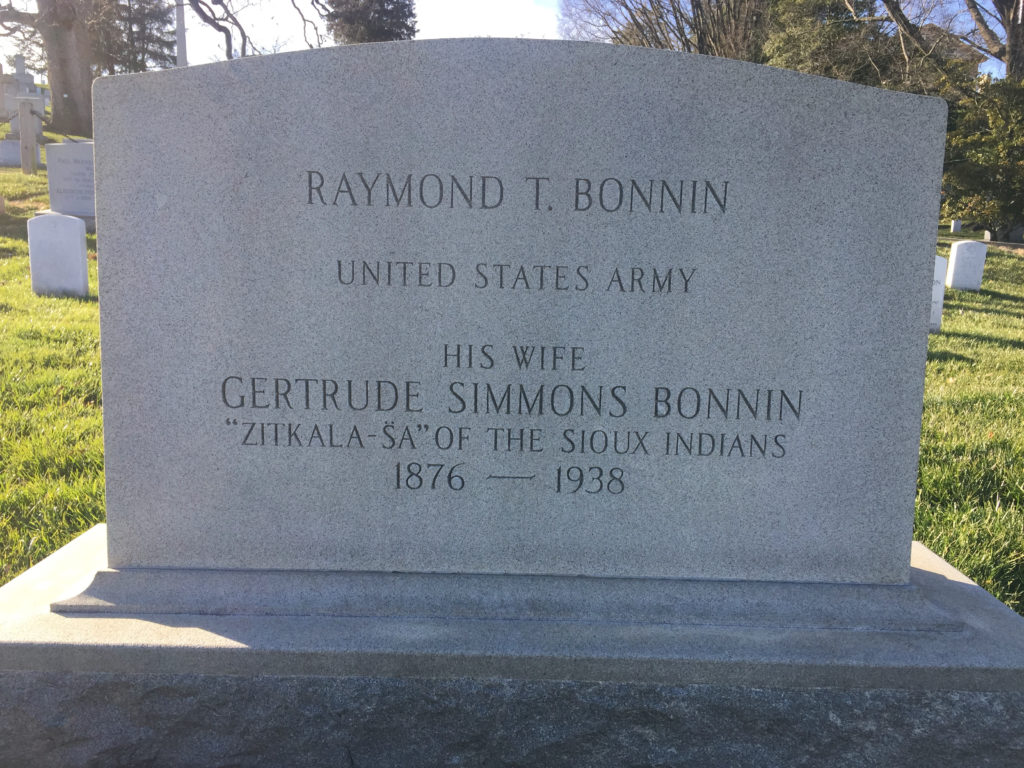

This is the grave of Zitkala-Ša, or Gertrude Simmons Bonnin, as she was known in the white world.

Born on the Yankton Reservation in South Dakota in 1876 and a member of the Yankton Dakota, Zitkala-Ša came of age during extraordinary rough years for the tribes. This is just when their resistance to white domination was being put down and the assumption that they would all so go extinct was common among whites. So she could hardly have picked a worse time to be born. To make it worse, her father abandoned the family when she was a baby, probably part of the greater depression and horror so many people in the tribes felt at this time. Then she and her siblings were stolen from their mother in 1884 by Quakers, forced to leave their home and attend an Indian school in Indiana. These experiences were horrifying to most. Forced to cut your hair, beaten for speaking your language, rampant sexual and physical abuse, this was all part and parcel of the genocide and the Quakers weren’t really any better than the rest. Part of what the Quakers and others did was strip kids of their names as part of killing their culture. So Zitkala-Ša became Gertrude Simmons.

She returned to the reservation in 1887. But like so many people who were forced out of their homes, she now existed between two worlds. She was most certainly not white, but she in many ways wasn’t quite Dakota either, with years of language and culture stripped from her. This experience of living between two worlds, neither of which really accepted you, would be a common story for those who survived the boarding schools. Like most Native peoples, Simmons did gladly adopt a lot of western culture. She grew to love the violin for instance. But she also resented the repression of her language and forced to sit through Quaker religious services. So she went back to Indiana in 1890 to finish getting a western education. She taught piano and violin to younger kids and then graduated in 1895.

Now, Zitkala-Ša was quite talented. And so she was able to go to college, at Earlham, the Quaker institution in Indiana. She had to drop out before she graduated due to financial issues, but among the projects she began at that time was collecting stories from the tribes and translating them into English for the future. Remember that the idea was that Indians had to assimilate or die and most people assumed it would be the latter. So even someone like her would have heard this and probably believed it to some extent. Anyway, after Earlham, Simmons went to the Boston Conservancy of Music to study violin and then became the music teacher at Carlisle, the giant Indian school run by the loathsome Richard Henry Pratt. They immediately clashed, as she wanted her people treated as humans and Pratt was determined to “kill the Indian, save the man,” as he notoriously had stated.

Simmons was all ready to be a good advocate for western society. But she returned to her home in 1900 and found white settlers overrunning the reservation, shocking poverty, and true desperation. She had found her way in white society. But most Dakota had not and it was sheer oppression out there. So she decided to dedicate much of her life to improving the condition of her people and the tribes generally. When she started writing about the hell of the Indian School experience in major magazines such as Harper’s, she was fired in 1901.

She went back to the reservation to help her family and collect stories for her book. That would be published in 1902, as Old Indian Legends, a way to get the stories of the tribes to the white public, with the goal of increasing understanding of them. She also took a job as a clerk at the Bureau of Indian Affairs office at the Standing Rock Reservation. There, she met and married a white Army captain named Raymond Bonnin. They were then assigned to the Uintah-Ouray Reservation in Utah, where they lived and worked between 1902 and 1916. During these years, Zitkala-Ša became more militant in her fight for Native rights. Her husband joined her. In fact, he was fired in 1916 for their advocacy and criticisms of the BIA, long one of the most corrupt backwaters of the federal government. She became a huge advocate for women’s suffrage, at part of her demands that Native peoples be granted citizenship and the full rights that white Americans had.

This advocacy took many forms. Some of it was working with whites translate Native culture into American cultural production, such as the opera she co-wrote with a BYU professor in 1910 that took the Dakota sun dance, prohibited by the federal government, and recast it for a broader audience. Sometimes, that advocacy was openly militant and radical. She reported on the beating of children at the Indian schools who refused to pray as Christians. As late as 1934, she reported on the theft of land and resources in Oklahoma of the so-called “Five Civilized Tribes” who had moved there and now had oil on their land that whites wanted.

Native Americans did get citizenship rights in 1924. But it was still up to the states whether they could vote or not and of course many of them banned them from voting. So in her later life, Zitkala-Ša focused her fight on this issue, again combining her passion for women’s suffrage with a broader sense of injustice that denied many Indians the right to participate in the nation that governed them. She joined the Society of American Indians as the group where she focused her activism. She edited their journal in 1918 and 1919. She became a national lecturer for the rights of the tribes, which were gaining more support among liberal whites at the time. In 1926, she and her husband founded the National Council of American Indians to try and bring the different tribes together in a single advocacy organization. This hadn’t really happened before. It’s not as if the tribes suddenly put aside their own grievances with each other once whites came along. So creating a sort of pan-Indian lobbying group was a big step. All of her work helped lead to the Indian Reorganization Act of 1934, the so-called Indian New Deal, which finally ended the Dawes Act allotments and began to give limited self-government back to the tribes, a very important moment in Native history. Simmons deserves a lot of credit for this. She died in 1938. She was 61 years old.

Gertrude Simmons Bonnin, aka, Zitkala-Ša, is buried on the confiscated lands of the traitor Lee, Arlington National Cemetery, Arlington, Virginia.

If you would like this series to visit other Native Americans of this era, you can donate to cover the required expenses here. Charles Eastman, whose From the Deep Woods to Civilization remains one of the best books to understand the issues of boarding schools and genocide, is in Detroit, and in one of the saddest and most disturbing stories out of the 20th century edition of the genocide, Jim Thorpe is in Jim Thorpe, Pennsylvania, a place he never even visited that bought his bones and changed its name to become a tourist attraction. Previous posts in this series are archived here.