Erik Visits an American Grave, Part 637

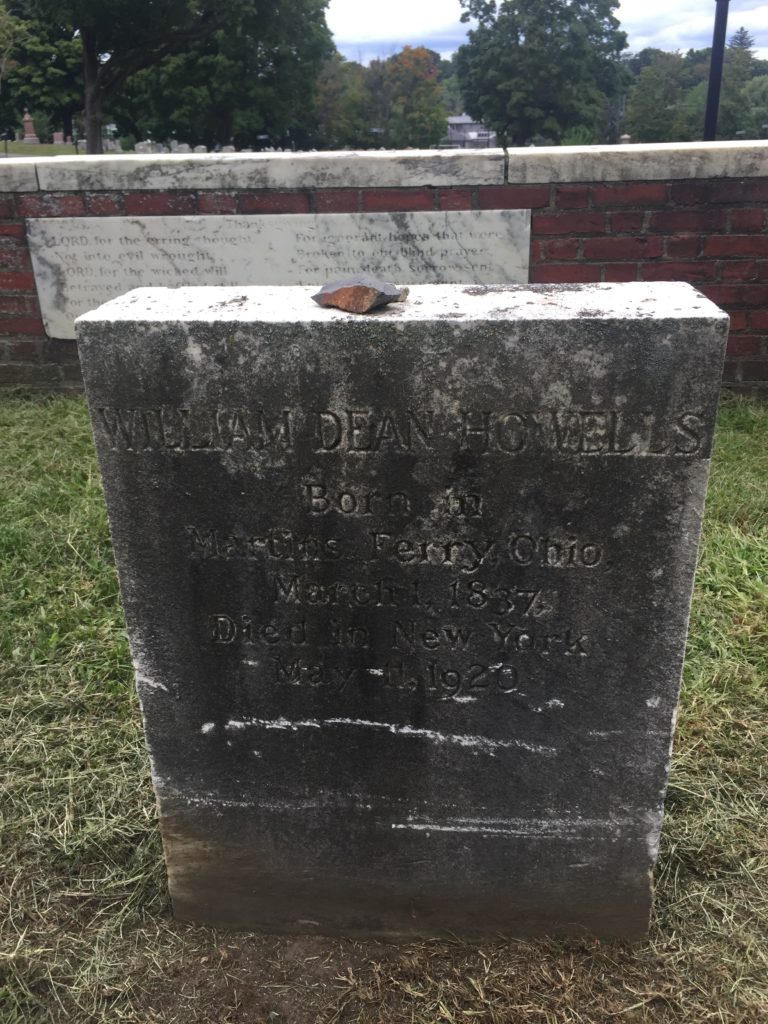

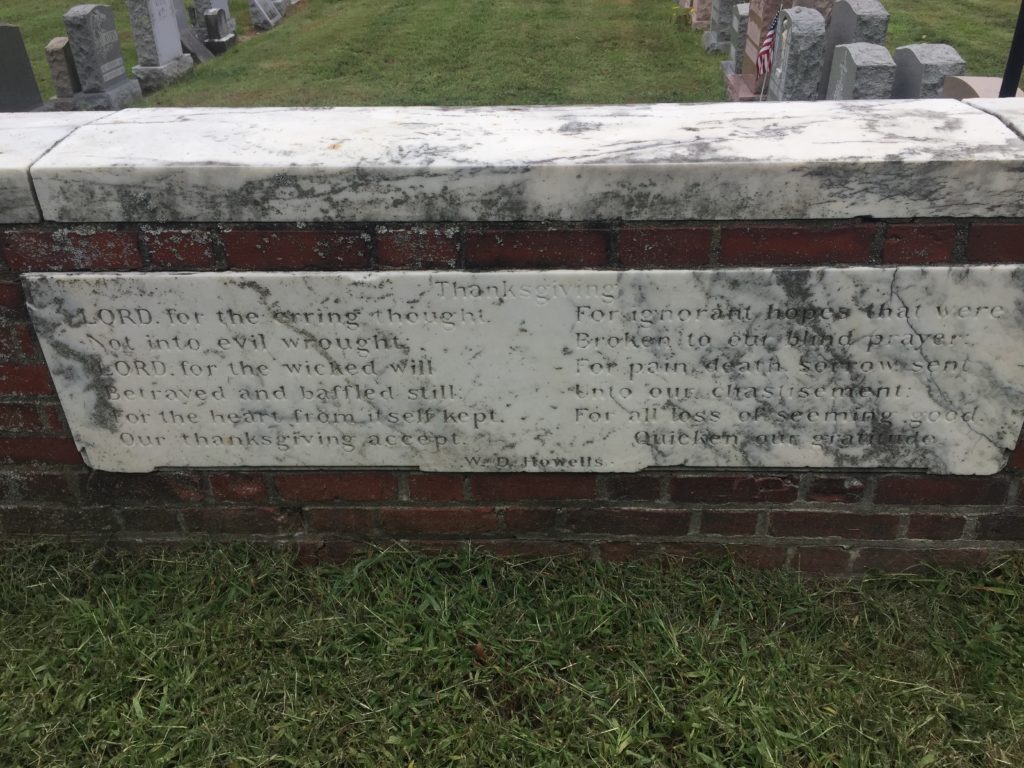

This is the grave of William Dean Howells.

Born in 1837 in Martinsville, Ohio, Howells grew up in a somewhat downwardly mobile family. His father was a Whig newspaperman and Swedenborgian follower who moved around a lot, looking for the next chance. Given that background, even though the family didn’t have much money, it’s not surprising that his parents encouraged the boy’s growing interest in literature. He started working at the age of 9, as a printer’s devil, which is a wonderfully colorful name for a kid who was a typesetter.

As the son of a reasonably prominent local Whig, Howells had a good start in advancing his career. In 1856, the Ohio state legislature hired him as a clerk. He started publishing his work in a journal called the Ohio State Journal in 1858, not only his own original publications, but his own translations of work in French, Spanish, and German. By 1860, Howells was a rising young star in American letters. As such, he began to spend time in the American literary capital of Boston, getting to know the leading people of letters of the time, including the James brothers, Ralph Waldo Emerson, Nathaniel Hawthorne, James Russell Lowell, and many others. He became friends with these people and at a very young age had risen into the American elite.

Howells’ meteoric rise really to fruition at the beginning of the Civil War. He was hired in 1860 to write Abraham Lincoln’s campaign biography. For his work, he was granted a patronage position at the American consulate in Venice, a plum post. In 1862, he marred Eleanor Mead at the American embassy in Paris. Mead was the sister of William Rutherford Mead, from the legendary American architectural firm of McKim, Mead, and White. In fact, one of their children was the prominent architect John Mead Howells, who would become one of the nation’s leading Art Deco designers.

In 1865, Howells and family returned to the U.S. and Howells became probably the most important literary figure of the Gilded Age. Yes, this was because of his own fiction, but it’s especially because of his work as editor of The Atlantic Monthly. He took over as assistant editor in 1866 and then gained total control in 1871. In that role, and especially in his embrace of realist writing, he became a mentor to and published many young rising writers such as Frank Norris, Hamlin Garland, Stephen Crane, Sarah Orne Jewett, Abraham Cahan, and Paul Laurence Dunbar. That Cahan was Jewish and Dunbar black was significant. For Howells may have had some of the prejudices of his time, but he placed literary quality above all and especially for Dunbar, he was the mentor who opened the white world to him. Howells also introduced Americans to many foreign writers, most notably Leo Tolstoy, who he wrote about at length. Howells’ novels were well-known, but it was his literary criticism at The Atlantic, and then later at Harpers, that really cemented his importance in American letters.

Howells started writing novels around the same time he took over The Atlantic. His first was Their Wedding Journey, in 1872, a minor work. His first real hit was in 1882, with A Modern Instance, about the decline of a marriage. The Rise of Silas Lapham, from 1885, is perhaps the best American novel about the Gilded Age. The story of a paint manufacturer from rural New England attempting to make it among the Brahmin elite is a brilliant expose of the hypocrisies of the American class system as it is developing, the crude capitalism of the era, and the snobbery that defined old money vs. new money.

Now, Howells was initially like a lot of his contemporary elites as a fervent defender of free-market capitalism as a moral impetus. This is why these self-described liberals, which are the Gilded Age equivalent of free-market fundamentalists, so hated labor unions or anything else getting in the way of the Holy Market. That included many abolitionists, for whom getting rid of slavery let the market take over, as it should. As the Gilded Age went on and the violence of the capitalist system became more overwhelming, many of his fellow elites who grew up before the Civil War became more defensive and called for blood at the slightest worker outrage at the horrors of their lives. Others, most notably Henry Adams, simply withdrew from public life, feeling totally adrift.

Howells was different. Much to the horror of many of his contemporaries, he realized that the unregulated capitalism of his time was a problem and he started to shift his politics to the left. The state murder of the Haymarket martyrs was a critical moment for him. He wrote against the trials and executions and wrote a novel vaguely based on Haymarket that was sympathetic to workers titled A Hazard of New Fortunes. He was already shifting before 1886 though. While he had been a big supporter of the awful Liberal Republicans to toss out Grant in 1872 and was a strong Republican up to 1884, when he cast his vote for Benjamin Harrison, he already started becoming interested in reform movements. Before this, Howells, who was connected to Rutherford B. Hayes due to his wife being related to Hayes’ wife, was given a month to write a Hayes campaign biography. Richard White, who uses Howells as his guide through his brilliant book on the Gilded Age, The Republic For Which It Stands, says it “reads like a book written by a man given a month off to write a book.”

But when Edward Bellamy published Looking Backwards in 1887, Howells became of the interested converts to his vision of the cooperative commonwealth that gave workers equality without social revolution. This was Howells’ sort of socialism, the type that clamped down on the rampant individualism of the Gilded Age but without class conflict or consciousness. His journey here was part of the broader and difficult American shift from its idealized and ideological belief in the glories of free market capitalism to the realization that America needed fixing to survive. When the U.S. decided to become an imperialist nation in 1898, he joined the Anti-Imperialist League. He certainly had his limitations however, being opposed to the growing women’s rights movement, which he felt took women out of their proper place in the domestic sphere.

Howells remained active to the end of his life. He was ridiculously prolific, publishing sometimes two or three books a year. There’s a reason only a few are remembered today, but the really good ones are in fact really good. Toward the end of his life, he naturally moved more toward memoir and remembering his travels, which had often taken him to Europe. In 1904, he was one of the seven founding members of the American Academy of Arts and Letters and was the organization’s first president. He took a huge blow in 1910 when his wife died, just a few weeks after his good friend Mark Twain died. But he lived on until 1920, when he died in his sleep at the age of 83.

William Dean Howells is buried in Cambridge Cemetery, Cambridge, Massachusetts.

If you would like this series to visit other Gilded Age writers, you can donate to cover the required expenses here. Frank Norris is in Oakland and Stephen Crane is in Hillside, New Jersey. Previous posts in this series are archived here.