Erasing Native Americans From Modern History

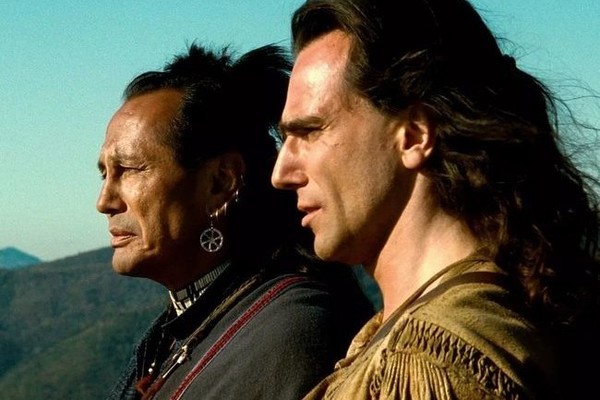

Evidently there is going to be yet another film version of Last of the Mohicans (yawn), this time for television. And as the Mohegan theatre director Madeline Sayet notes, this is yet another example of Hollywood, and Americans generally, erasing Native American history, assuming like Cooper that there is a last Mohican, when that is very not true.

So I have to ask: Why tell The Last of the Mohicans again? There have already been nine film versions of the story, and casting decisions can’t redeem it. Producing any version of The Last of the Mohicans perpetuates erasure and reinforces genocide — and those sentiments begin with the title. Then there’s the way the attached talent talks about the story: “I am profoundly excited … to be bringing a new light and perspective to this period in our history,” said Nicole Kassell, while Fukunaga has said, “We have the chance to revive the forgotten ancestors that define American identity today.” Both of their quotes fill me with dread that this new version will continue to promote Cooper’s work as factual history when the reality couldn’t be more different.

The Last of the Mohicans ends with the death of a Mohegan named Uncas. In actuality, the real Uncas was not in upstate New York at the time, and was not from there. Uncas was the chief of the Mohegans in Connecticut, not the Mahicans in New York. But most importantly, Uncas was not the last: He is my ancestor. I exist only because he survived.

Despite what Fukunaga says, my ancestors aren’t forgotten, and their story is far more interesting than that of the fictionalized characters in Cooper’s imaginary tale. Mine is a storyline of resilience, yet in Cooper, Kassell and Fukunaga’s world, I don’t exist — and that erasure begins with the title, never mind the content.

Making yet another Last of the Mohicans isn’t just damaging, it’s lazy and unimaginative. Think of the new “American classics” being written by Native people. In 2019 alone, Tommy Orange’s There, There became a finalist for the Pulitzer Prize, Joy Harjo became Poet Laureate, Larissa Fasthorse won the Pen America Literary Award for Theater, while Lisa Brooks’ Our Beloved Kin: A New History of King Phillip’s War won the Bancroft Prize. These are only a few examples of groundbreaking Indigenous writers telling Indigenous stories. These are stories of resilience and survival — stories that could have positive impacts on the world around us and contribute to the visibility, and inspiration, of Native people. Instead, The Last of the Mohicans will continue to tell us that we don’t exist.

The United States government’s policies to erase Indigenous peoples have ultimately failed, but the myths those policies created are still here, as is the desire to retell stories, like Cooper’s, time and again. It’s time for those storytellers to leave those stories behind and accept we exist.

It’s time to tell a different story. A new story. A powerful story. A healing story. Uncas, my ancestor, chief of the Mohegans, wasn’t the last and he never will be. He is the reason I am alive today, and I am exhausted by how little this conversation has moved forward since my mother was my age, writing her rebuttal on her typewriter.

One of the biggest problems in American race relations today is that Native Americans keep having to jump up and down and remind people they even exist and that very much includes people who are left of center and should know better.