Erik Visits an American Grave, Part 638

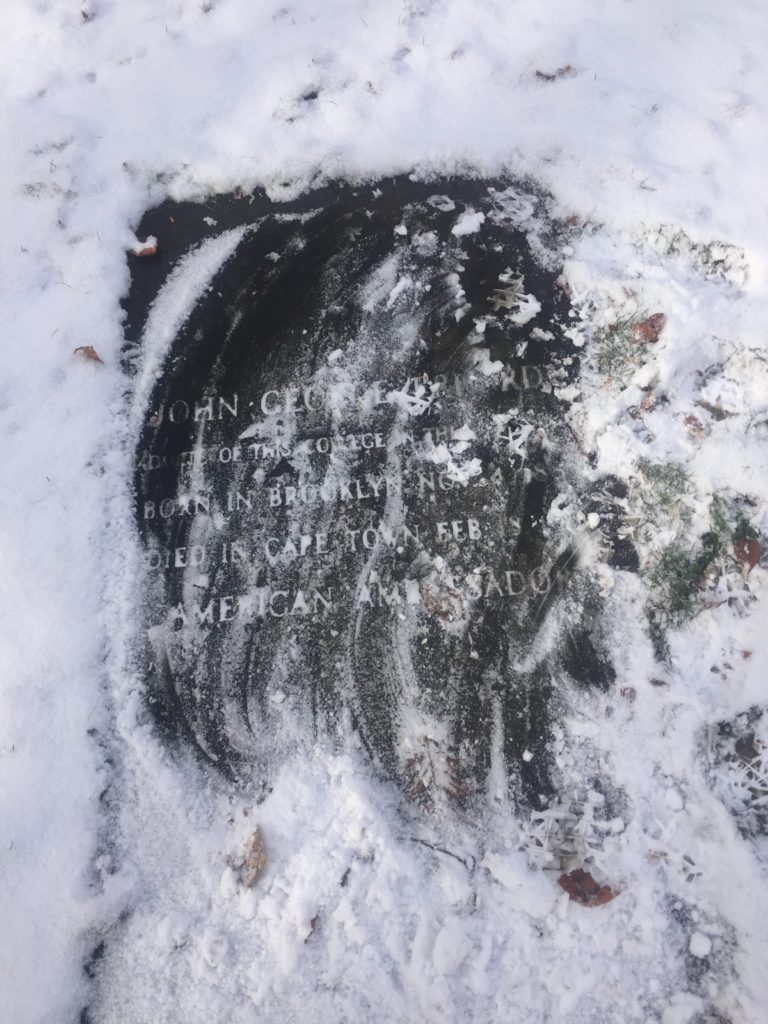

This is the grave of John Erhardt.

Born in 1889 in Brooklyn, Erhardt graduated from Hamilton College in 1915 and went to law school at Fordham. He volunteered for World War I when the nation entered that conflict in 1917, where he was a staff sergeant in the Army Engineers. After the war, he was admitted to the bar in 1919 and then went to Europe to study at the American School for Classical Studies in Athens and then further studies at the University of Bordeaux in France. He then entered the Foreign Service and had a very interesting career as a diplomat that would take him up to his death.

Erhardt started his diplomatic career in Athens, where he was consul from 1920 to 1924. One of the things that Erhardt specialized in was refugee relief, an important skill in the horrors of the twentieth century. Of course, he didn’t train for this, he just found himself in the middle of awful conflicts. He was in Greece during the 1919-22 war between that nation and Turkey. After the Turkish army retook Smyrna to effectively end the war, he assisted in the moving of 5,000 refugees to Greece. After his time in Greece, he was assigned to the significantly less exciting consulate in Winnipeg. He then spent four years in Washington at the State Department’s commercial office. He became an expert in trade issues at this time and was a representative to many international trade conferences in the early 1930s.

In 1930, he was named the American consul in Bordeaux and then by 1933 he was in Hamburg, where he managed to get hundreds of refugees out of Nazi Germany to the U.S. In 1937, he returned to the U.S. once again, where he was named the inspector of American diplomatic posts. Then in 1940, it was Erhardt who coordinated getting Americans out of Britain during the Blitz. He was consul general and first secretary at the British embassy under Joseph Kennedy, father of the future president, fascist quasi-sympathizer, and then ambassador to Britain. In 1941, Erhardt came back to the U.S. again, where chief of the division of foreign service personnel at the State Department.

Erhardt became an advisor to General Mark Clark during World War II. After the war, Erhardt, now a highly respected diplomat, was named ambassador to Austria while Clark’s troops occupied the American part of Vienna, a complex and very messy period best understood by watching the astounding film The Third Man.

In 1950, Erhardt received another high-profile post: ambassador to South Africa. This is the moment when the apartheid regime was really entrenching itself and when the U.S. was openly allying with racist regimes as the bulwark against communism, which helped define all the freedom struggles as communist-sympathetic, including the African National Congress. Erhardt was highly worried about the growing racial tension in South African society and what it might mean for regional stability. He wanted America to “cautiously and without giving offense” urge white South Africans to soften their racial policies and to bring those policies “closer to the general standards of western democracies,” though it’s not as if the U.S. had any room too tell other nations what to do about this in 1951 as the South was defending Jim Crow with increasing violence. He also criticized South Africa using anti-communism as an excuse for its open oppression of black Africans. Erhardt’s major goals as ambassador was to open up South African natural resources to American companies and to strengthen the nation’s support of the West in the Cold War.

By this time though, Erhardt’s health was starting to fade. He complained about not feeling well and blamed the moving of the embassy from the high elevation of Pretoria to the sea level elevation of Cape Town. But that wasn’t really the issue. He died in his sleep of a coronary thrombosis in February 1951. He was 61 years old.

John Erhardt is buried at Hamilton College Cemetery, Clinton, New York.

This grave visit was funded by LGM reader contributions. Many thanks! While admittedly a minor grave, it’s also an interesting quick look into American foreign policy history and the various issues in which a diplomat might find themselves over the years. If you would like this series to visit other American diplomats, you can donate to cover the required expenses here. Nathaniel Davis, who was ambassador to Chile when the U.S. worked with Augusto Pinochet to overthrow the Allende regime, is in Kent, New York. John Peurifoy, who was ambassador to Guatemala when the U.S. decided to overthrow Arbenz, is at Arlington because of course the nation honors its worst people. Previous posts in this series are archived here.